A REMARKABLE story directly linking Croke Park on the day of Bloody Sunday with the magnificent venue of the modern era provides a poignant family connection a century on from those tragic events.

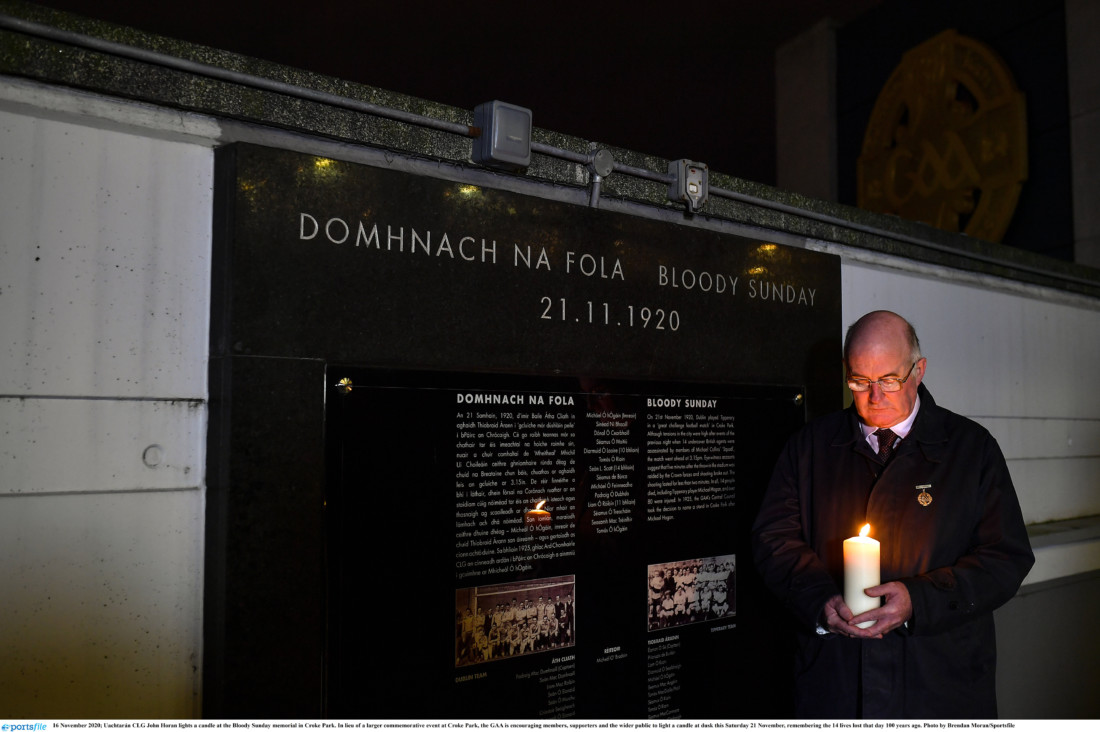

Commemorations will take place on Saturday to mark exactly 100 years since 14 people, including the Tipperary player Michael Hogan, were killed by British forces.

Many stories have re-emerged in recent years surrounding the tragic events of that day. Michael Foley, author of ‘The Bloodied Field’, has helped to bring to life once again the lost human impact of that occasion and the deep personal memories of those families directly touched by tragedy.

This Saturday night, the GAA will lay wreaths in Croke Park at the site close to Hill 16 where Michael Hogan was shot. There will also be 14 torches lit on Hill 16 to remember the 14 people who were killed.

Gaels across the country are also being asked to light a candle in the windows of their homes to mark the anniversary.

Among them will be the architect who designed the new Croke Park, a stadium that is now such a vivid and living monument to the GAA’s historic place in Irish society.

For former Tyrone player Des McMahon, who now lives in Dublin and is originally from Beragh in Tyrone, will have his own very special family reason to look back with particular poignancy on the events of November 20, 1920.

On that day 100 years ago, his father Jim, played in Croke Park and, like so many thousands of others, was engulfed in the panic which ensued when the shooting began just 10 minutes into that fateful clash of Dublin and Tipperary.

In later years, Jim McMahon was to represent Tyrone against Cavan in the 1934 Ulster Final. On Bloody Sunday, his day began with an important match at Croke Park. It was the replay of the Dublin Intermediate Championship final between Erin’s Hope and Dunleary Commercials.

Originally from Ballybay in Monaghan, Jim McMahon was a student at St Patrick’s Teacher Training College in Drumcondra, just a stone’s throw from Croke Park, and playing for the Erin’s Hope side which drew from the college.“My father was a first year student on a two-year course at St Patrick’s in Drumcondra,” Des McMahon said.

“Students from there at that time played their club football with Erin’s Hope and he was part of the team which that year had reached the final of the Dublin Intermediate Championship.

“The final was played on the morning of Bloody Sunday in the game before the match between Dublin and Tipperary. My father, in his later years, told me and my brother, Seamus, the story of how he happened to be in attendance.

“There wouldn’t have been any dressing rooms in Croke Park at that time and several of the club players were asked to remain togged out to act as officials and linesmen. The fact that they would still have been in their kit made them easily recognisable within the large crowd that was expected.

“My father was terribly disappointed not to have been picked for that role because he had no money to pay his way back in for the senior game, which was a couple of hours later. Anyway, he dodged and bluffed his way to stay in the ground and was there when the shooting began.”

Des McMahon believes that his father was located somewhere on the Cusack Stand side when the firing began. Like so many others, the race for the exits began immediately, and only the help provided by a Sligo man ensured that he got away safely.

“Everybody was trying to get out and he was caught in a bad position at the Cusack end, even though the Canal End would have been worse.

“My father wasn’t terribly big and he was trying to climb a wall to get away. A fellow student had been up on the wall already and he lifted my father up as well. They then dropped down into what was then the Belvedere Rugby Ground and got away into the nearby streets.

“Many years later, my brother Seamus was in his dental waiting room in Sligo when this man came in and asked him did he happen by any chance to be related to Jim McMahon. That man was called Sean Devanney who was head teacher in a place called Ballinacarrow between Sligo and Castlebar.

“That generation were very reluctant to talk, but now and again they would open up and he told me and Seamus those details. Unfortunately, I got no further details about the game or his attendance at the county game later that day.”

Seven decades later, Des McMahon was commissioned as the architect for the new Croke Park, including the Hogan Stand which is, of course, named after Michael Hogan, the Tipperary player killed on Bloody Sunday.

His ground-breaking design has been heralded across the world, and provided the perfect backdrop for new heroes to emerge on the Gaelic games scene and prove their worth on the greatest stage of all.

Des himself took great pride in being on Hill 16 for Tyrone’s historic first All-Ireland win in 2003, and often thinks back to his father’s time and the Red Hand teams, including those which he played on in the sixties, that never quite got close to winning the ultimate prize of the Sam Maguire Cup.

Nevertheless, he always knew and was acutely aware of his father’s involvement in Croke Park on that day, even when he was working on the design for the new stadium.

It’s something which he chose instead to keep as a personal family memory until now, the 100th anniversary of those terrible events.

But he is proud of that involvement, and often thinks of what his father would have made of how much the Croke Park of those years was transformed into the ultra-modern stadium of today.

“The estimate is that there were around 10,000 people in Croke Park that day. It’s amazing that my father was there and very poignant to think that subsequently I was to obtain the role of being architect of the new Croke Park,” he added.

“I have a very, very deep pride in that connection and I often think of how proud he would have been of that connection as well. If he had lived to see the new Croke Park I’m sure he would have been amazed by how much it had changed.

“Over the past few years I’ve often thought about researching the events of that day and my father’s particular involvement more fully and it’s definitely something which will need to be done when the coronavirus restrictions are finally eased.”

Jim McMahon and Erin’s Hope didn’t manage to win that Dublin Intermediate title all those years ago. A 2-2 to 0-2 defeat in front of what was described as a sizeable attendance at Croke Park provided disappointing.

However, his footballing story didn’t end there. After moving north to take up a teaching post in the heart of Tyrone, he lined out for the county team in the 1920s and 1930s, the highlight being reaching that provincial final in 1934.

His son, Des, was to follow in his footsteps in the 1960s and their family story illustrates the deep font of folklore which exists around that stirring and tragic period in Irish history. It’s one which resonates down to the present day and the weekend events will no doubt prompt long-lost memories of similar tales of connections to that infamous occasion.

By Alan Rodgers

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere