The GAA, it’s bigger than cycling

You can’t help being struck by how much sports coverage isn’t actually about sport at all.

Cycling is a great example. Practically all that huge swathes of the population know about the sport is how it exists in relation to Lance Armstrong.

The Tour de France is defined for many by drugs and the culture Armstrong embodied more than anyone else in the sport.

And so we see Chris Froome being grilled on believability or otherwise of his power data. The race is almost a side-show.

Similarly the credibility of athletics is a parallel conversation which takes place with almost every race you watch. The feats of human achievement in the stadium are jaw-dropping, but every world record comes with a question mark over it. Were they doping?

Soccer is another sport where the game often plays second fiddle. Huge sections of a programme on soccer can be devoted to the financial health of clubs, their transfer business and various other accounting arcana.

Thanks to the Glazers, Randy Lerner et al, many soccer fans now have a more sophisticated understanding of investment with leverage than they do of their own mobile phone bills.

With game so tedious these days, the only interest there is in it for many people is their Saturday accumulator. The amount of money involved in betting now means that match fixing is a rising problem.

You could argue that GAA coverage is guilty of this sin too. Just this week we have the Director General Páraic Duffy holding forth on the fuss around our broken fixtures programme.

But I would argue that there is a crucial difference here.

In GAA, where money is not yet the sun around which our games orbit, the coverage which doesn’t directly relate to sport focuses more on issues of administration and matters of identity.

In cycling, athletics and soccer, coverage not directly related to the sport itself sometimes seems to outweigh the volume of actual reporting on races and games.

That comes down to money, the fascination it can exert on highly driven athletes, and correspondingly, the wider public’s interest in how that corrupting dynamic plays out.

Where money is a key motivator it seems to have a uniquely poisoning effect on a sport.

When money is involved, any underhand trick or manoeuvre seems to become justified. Motivations are jaundiced, refracted through the perverting lens of lucre.

In cycling and athletics the incentives to dope are huge. Money and the security that brings, the prestige of being a human being capable of operating on the very edge of endurance, and self-esteem – if you can sell yourself the story that you’re not really a cheat because everyone else is doing it.

The money in soccer at the top level defines players’ relationship with the game. It means they can slack off with the reserves because life changing amounts of money are still coming in every week. It also means they can take long term risks with their bodies in pursuit of bonuses or fall victim to the siren call of betting cartels.

The fact that clubs are now little more than just another asset in an investment portfolio means they are increasingly removed from fans and supporters.

People seem to labour under the illusion that the GAA is immune from these ills. But the reality is that the only thing standing between us and the kind of sickness which has so devalued cycling, athletics and soccer is amateurism.

By taking money out of the equation, GAA continues to be about the sport. We can’t pretend we don’t have our share of off-the-pitch problems, but they aren’t issues which undermine the very credibility of the sport itself.

Are there players doping in the GAA? Probably, but no one imagines it’s on a scale comparable to professional sports. After all, when the potential costs so dramatically outweigh the rewards it doesn’t make a lot of sense.

Is match fixing a big issue? That seems doubtful. Do we spend endless hours pondering the financial health of clubs and counties and their ownership structures? Thankfully, no.

At the end of the year pundits ask in amazement how GAA can sustain the interest it does in the face of other major sporting event like rugby world cups, Olympics, soccer world cups and the like. For me the answer is simple.

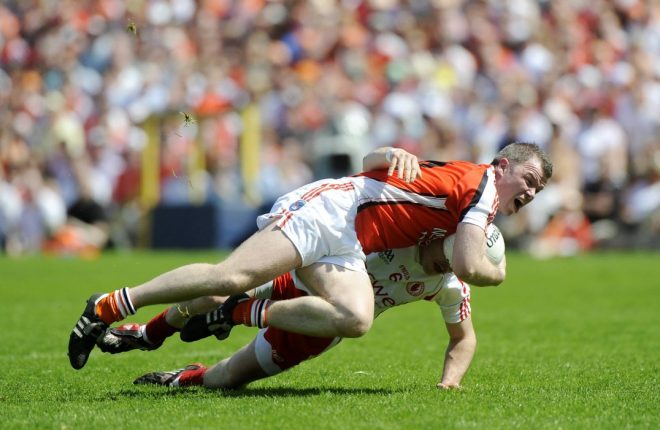

Amateurism means that the games are generally the central focus of GAA coverage. It gives our sport an inherent credibility and a connection with fans and supporters. There is no fakery or artifice in a National League game.

The players are giving their all for the team and the fans, nothing else. The authenticity of that passion and commitment is something that sports enslaved to money can never replicate.

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere

John Hughes took the opportunity to use Colm Cooper's retirement as an opportunity to recall the rise and fall...

John Hughes highlights the secret's of the GAA's success.