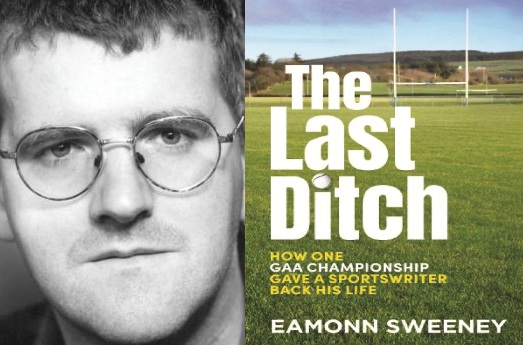

IN 2000, the sportswriter Eamonn Sweeney was at the top of his game. A successful novelist and sports journalist, he was a regular on TV shows, a drinker, a socialiser, an intellectual and a 32 year old man in a loving relationship. In his new book ‘The Last Ditch”, his first in 20 years, he tells the story of how one day in 2000, his life began to fall apart. I interviewed him last week, his first interview in 20 years…

“My curse fall on Sweeney

for his great offense

… it will curse you to the trees

a bird brain among the branches.”

Seamus Heaney, Sweeney Astray.

A Swiss newspaper recently featured a job advertisement for a hermit:

‘Hermit Wanted – Friendly recluses only please. €822 a month plus free lodging in the hermitage, hidden in the rock face of a gorge.’ The job came up when the previous hermit resigned after 5 years because there were “too many tourists noseying around.”

The first hermit was Saint Anthony of Egypt, who retreated to the desert to dedicate his life to silence and contemplation. Eamonn Sweeney retreated to his house in Skibbereen. Unlike Saint Anthony, there were no tourists to interrupt his lonely vigil.

January 2024 – High Noon in Ardrahan

‘It was the kind of station where gunslingers wait for trains while a rusty weathervane creaks in the breeze and vultures perch hopefully overhead. The sight of the approaching train made my heart pound.. It lumbered to a stop in front of me. If I could sit on my own I might be OK. I stepped on, feeling a familiar vertiginous sensation as I did so. The doors shut with a whoosh. The trap was closed. It was High Noon in Ardrahan. If I stayed on the train my life would change. If I didn’t, I would trek back into the village, contact the editor of this book and tell her I couldn’t write it. The fears that had imprisoned me for decades would win yet again…’ (The Last Ditch)

We meet, not in person as we had planned (Eamonn baulked), but by zoom, only after his daughter Lara set it up for him. A dog is barking in the background. Ireland’s greatest living sportswriter is happy but flustered.

Me: I cannot believe it. You actually exist.

Eamonn: Neither can I.

Me: And you have a mobile phone.

Eamonn (excitedly): I only got the mobile phone last year to do the book. It is the first phone I ever had.

We both laugh. Though it is not a laughing matter.

June 2000: The madness of King Lear

‘I had no inkling of what was about to hit me. I’d just published a second novel, I’d been living in west Cork for two years, I was covering GAA for the Irish Examiner and a few days earlier I’d done an interview with Dara Ó Cinnéide, who spent more time talking about his (excellent) taste in foreign films than about the upcoming match. The young fella I was thenhad the bumptious bulletproof confidence of a soldier worried the First World War will be over before he gets there and wins a few medals.’

Me: What age where you?

Eamonn: 32.

Me: You were part of the whole GAA fabric. Every manager, every player, everybody knew who you were. You were beloved. You were never off RTE..

Eamonn: (laughing) I was always on The View with John Kelly. It’s true I did do a lot of telly. I even did Questions and Answers. I was the life and soul of the party. Things were going great for me. Then, it happened.

Me: Go on.

Eamonn: I was strolling into Killarney stadium. Cork were playing Kerry. I love this stadium and I was feeling good about life. As I made my way round to the press box, I got hit by a bomb. My heart was pounding. Sweat came cascading off me. My face was shaking. Through the haze, I could hear someone saying, “he’s sweating like a horse.”

Me: What was it?

Eamonn: Terror.

Me: Of what?

Eamonn: Nothing.

Me: Explain

Eamonn: I couldn’t move. I couldn’t put one foot in front of the other. I was stopped. This is scary for me to think about Joe.

Me: I’ve never met a writer who writes with such effortlessness, such facility, such joy. And here you were in your comfort zone going into Killarney to see Cork and Kerry. A romantic poet about to conjure up all of the magic of this ancient fixture.

Eamonn: Exactly. Was I an insane person? King Lear’s lines ‘O let me not be mad, not mad, sweet heaven. Keep me in temper, I would not be mad’ kept coming to my mind.

Me: Was it the drink?

Eamonn: I was a drinking man but it wasn’t the drink

Me: Did you take psychedelic drugs when you were younger?

Eamonn (laughing) No, but I wish I had.

Me: Was it your childhood coming back to haunt you?

Eamonn: No. I had a happy, boring upbringing.

He was invaded by an invisible enemy. At first, he tried to fight it off. Eventually, he was overwhelmed. Beaten. Paralysed. Eamonn describes it as “a demonic possession.”

Planes, trains and automobiles

“Flying bit the dust after a 2001 episode when I had such a spectacular panic attack that I was allowed to leave a plane getting ready for take-off at Venice Marco Polo Airport. The memory of the incident remains so terrifying I haven’t flown, or left the country, since.”

Me: How bad?

Eamonn: It was shocking. I was roaring ‘Let me off.’ If it was today, they would have arrested me. I had to get off that plane. I was gripped with terror. I knew that something terrible was going to happen to me if I didn’t.

Me: You were like a man on a melting iceberg. In the book, you write, “The walls closed in slowly. Boats went off the menu in 2003 after another panic attack on the ferry from Baltimore to Cape Clear where I barely managed to resist leaping into the sea.”

Eamonn: That was actually on the occasion of my daughter’s christening. I was supposed to go out on the ferry in the morning and I turned down one boat after another. I never got on a boat again. You can’t jump off a plane, but you can jump off a boat.

Me: Would you have felt relief jumping into the sea?

Eamonn: Yes. I would have done anything to escape the terror.

Me: Jesus Eamonn.

“Rail travel lasted another six years until 19 November 2009 when sitting on the Galway train to Dublin awaiting departure I suffered an attack of such disorientating strength and suddenness that I scrambled on to the platform without taking my bags with me.”

Eamonn: I was able to suffer the train for a while alright. I was still drinking at that stage, so the three pints gave me the courage to board. But that was it. It took me ages to get those bags back as well.

Me: Did you get on the train?

Eamonn: Yes. But I had to get off. I was pacing up and down. People would have been thinking that fella is not 100%, shove over for Christ’s sake so he doesn’t sit down beside us.

Then, one day not long after, the buses were gone too. Taking them was torture but I could do it, then one day, I was taking the kids up to Galway on the bus to see their grandmother and I couldn’t.

Me: Where did that leave you?

Eamonn: Comprehensively stuck

Me: The house?

Eamonn: The house.

Me: No phone?

Eamonn: No. I was terrified and totally dissociated from the world.

Everything changed when he took that Ardrahan train at high noon. Like Gary Cooper, he faced his villains and gunned them down one by one.

As for the book, it is masterful. Like John McGahern, Eamonn passes the Dungiven changing room test, the only test worth passing. That is to say he can walk with kings or paupers. He can talk Dostoevsky or the Dubs with anyone. His brilliance is democratic, understandable. The book is one that only a very great writer could write. An interweaving of junior championship and bad referees and obscure Russian novelists, of emigration and drunken Cork girls on a train singing Shania Twain. Of Shakespeare, Alexandrovich Gonturov and David Clifford.

Of Clifford, he writes, ” His materialisation on the shores of Lough Leane was a bit like Clark Kent’s sudden arrival in the town of Smallville, Kansas.”

Me: I couldn’t stop laughing at that line. I imagined Mr Clifford senior running into the house in Fossa, shouting, “Sweetheart, you better come and see what just landed in our back field.”

Eamonn: That’s exactly it. A superman. With no earthly explanation.

Of his father, he writes,

Especially for men my age and older, reared in an era where your father came in from work, flopped down in a chair, was handed a paper and given his dinner while wearing an invisible but highly effective ‘Do Not Disturb’ sign on his chest before heading off to the pub later that night to seek the company of other fathers who were, as my paternal grandmother observed, keen on combining the comforts of the married man’s lot with the freedom of the bachelor’s. This blithely semi-detached attitude to fatherhood meant our mothers were what we had left.

The passages about his mother evoke the Derry poet’s description of peeling potatoes with his mother,

‘When all the others were away at Mass

I was all hers as we peeled potatoes…

Her breath in mine, our fluent dipping knives

Never closer the whole rest of our lives.’

His mother, like all decent GAA people, was a life long referee hater. After Galway beat Mayo in the championship last year, he sets out her analysis of the game.

‘I stayed in Spiddal with my mother and discussed the game. ‘The ref gave everything against Galway,’ she said, as she’s said after every single game the county ever played.’

Me: Was that not the day where Mayo were winning by two points in injury time and David Gough gave Galway three frees in a row to win it?

Eamonn: Yeah, three dodgy frees in a row. I said that to her and she just said, “Well he gave Mayo everything else.”

His father was a Kilkenny man, who he describes as a Kilkenny supremacist. “I remember going down with him to the 1999 final when they played Cork and him telling everyone in a loud voice that he hoped Kilkenny hadn’t won by half time because it would ruin the spectacle.”

Me: What would he have made of Shefflin managing Galway?

Eamonn: The same as Cody.

Me: There is something forever about Cody. That notorious handshake with Henry in Salthill where he held him in an iron grip. Though nothing was said, it was a handshake that reverberated around the country with the message, “Henry, you are a traitor.”

Eamonn: It was like one of those handshakes in the Godfather where the Don shakes someone’s hand and you know your man’s going to be taken for a long ride out into the country in the next scene.

In the book, the author feels sorry for Shefflin.

“One of the three or four best players of all time, he’d chosen to manage Galway instead of waiting to succeed Brian Cody as Kilkenny manager. As a player Shefflin had radiated imperious self-assurance and seemed the personification of that Noreside sang-froid which had got his county out of so many close shaves. All traces of it had gradually vanished from his demeanour as a manager. That day in Galway he cut a tormented figure. ‘Shut the *** up, Henry,’ shouted a Kilkenny fan behind me as Shefflin berated the ref. ‘He’s not even watching the match, he’s so busy complaining.’

On Jimmy McGuinness, “Jimmy is an avante garde artist. He invented nihilist football, with the aim of finding out how negative it could get. He is a modernist, like Samuel Beckett or John Cage (I nodded knowingly but had to look Cage up. He was ‘a pioneer of indeterminacy in music’ whatever that is.)

Eamonn: I think Jimmy would have liked to play football without the ball. His ultimate aim was a game without scores. Now, he is an apostle of adventure.

Me: He is magnetic. The Rasputin of Gaelic football.

Eamonn: I can imagine him out in the jungle leading his guerillas to victory. Talking to them in some clearing, saying, “We hit the capital in two weeks, comrades.”

Me: (laughing) Yes, you could imagine Jimmy pointing to Paddy McBrearty, in a bunker, under heavy fire from government forces, saying, Paddy, it is time to sacrifice yourself for the group and Paddy saying, “Thank you for choosing me Jimmy. It is a great honour.”

The book is many splendoured. We discover that Eamonn’s grandfather’s first cousin’s son was John Ford, the greatest film director of Hollywood’s classic era. He writes,

‘Returning to Ireland to make The Quiet Man, Ford visited his relations and expressed

a desire to take some dilisk back to the States. My mother was dispatched to bring some in a jar to Lord Killanin’s house where the director was staying. He rewarded her, in true Western style, with a fistful of dollars. My mother’s sisters Maura and Bríd got parts in the film as extras and my mother got to visit the set, where she watched John Wayne and Maureen O’Hara go through numerous takes of the scene where they shelter from the storm together.’

His description of GAAGO is priceless, “like the infamous proposed water charges of blessed memory, there was no point lecturing people about the necessity to pay or deriding their opposition as ‘populist’. They just didn’t like the idea. There was no point telling them how reasonable the price was because they suspected, as with the water charges, that once the principle was accepted nothing could prevent the price being jacked up in the future.”

Who else would describe the Galway footballer Shane Walsh as ‘objet d’art’? Genius and hilarity is everywhere in these pages. I laughed out loud at his description of two posh ladies from Bray discussing property on the train. ‘I wish it would gentrify faster. It needs some restaurants and there are still a lot of council estates.’

He has found, to his surprise, that writing the book has been a powerful antidote to his dread. “There’s a musician I really like called Buddy Guy, great blues guitarist and singer. The thing about the blues is he says, you can only sing the blues if you have the blues, but when you sing them, you lose them. And writing the book has somehow become part of the cure.”

In the final chapter, he writes,

‘I’m one of the least macho men you could meet. I can’t drive, I’ve never been in a fight and I know the words of three dozen Stephen Sondheim songs. Yet what did me more damage than anything else in my struggle with anxiety was a refusal to ask for help or admit how bad the problem was. I thought it would show weakness. I thought it would be unmanly so I tried to man up and the problem just got worse. Some things which work in the dressing room and on the field may prove a real menace for players in everyday life. The macho code might suit some men but it’s toxic for a lot of others.’

Sweeney, that accursed 7th century king of Ulster, assaulted a priest and was cursed by being turned into a bird, banished to a life in the trees. But in due course, the bird found liberation through song and poetry, and ultimately, peace within itself.

The curse that set upon Eamonn remains a mystery to him. Where it came from. Why after all these years it is finally leaving him. But like that ancient bird, he is finding peace within himself.

As we are finishing up, I say, ” Do you really know the words of three dozen Stephen Sondhein songs?” “I do Joe, by heart.” “Give me a blast,” I say. “Too soon Joe. Too soon.”

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere