WHEN the well known badge kisser Mickey Harte was being presented with the keys to his new Renault in Celtic Park, proudly wearing his Derry tracksuit, he said that his Tyrone assistant Gavin Devlin was “the best coach in Ireland.” The best coach in Ireland went on to play an offside trap in a game that doesn’t have offside, we conceded seven goals in two home championship games and became the laughing stock of the country.

To be fair to the Derry board, they are not easily humiliated. This week they hired Tyrone man Paddy Tally, a manager who Mickey Harte sacked as his coach in 2004. The last time Paddy coached Derry, we went from Division One to Division Four. He went on to manage Down for three seasons, which no one remembers. Then, he was hired by Kerry as their coach. Now, he is the latest fake Derry manager.

One week ago, he was unveiled at a press conference in the same manner as Dundalk United’s new striker, wearing his Derry tracksuit, swearing loyalty to us until another job comes along, maybe Offaly after Mickey Harte moves to Carlow or Leitrim (assuming Mickey Graham doesn’t change his mind again).

For Paddy – like the rest of our professional managerial cartel – the main qualification is to be available and biddable. Nothing worse than an awkward insider who wants to do things his way. After that, it is simply a matter of fleshing out his CV (presumably glossing over the bit about his involvement in taking Derry to Division Four).

The essential component in sport, and in life, is loyalty. In the sacred crusade for Sam Maguire these Derry players want to embark on, Tally, like Harte before him, is the weak link. The crucial thing is, as Pat Gilroy eloquently told his young guns in 2010, to “play for a cause bigger than yourselves.” They went on to give it everything they had for that greater cause, knowing that their manager was doing the same. Knowing that he had their backs, on and off the field. Knowing that his loyalty to them and to the cause was unquestioning and absolute. When any of those players has a personal problem, to this day, it is Pat they turn to. Which is the entire point of the GAA.

In Rory Kavanagh’s autobiography ‘Winning,’ he explains the crucial importance of ‘real’ loyalty. Jimmy told them from the beginning that the mission they were on was of and for the people of Donegal. They visited the schools. They talked about the history of the people. They trained at clubs the length and breadth of Donegal. At that first meeting when Jimmy told them they would be Ulster and All-Ireland champions, they thought he was mad. But they trusted him, and he trusted them. This is because they were all in it together, because, as Rory explains, they were on a journey bigger than themselves. Jimmy’s loyalty to them was absolute, even overbearing. So no matter how tough Jim made things, they did it without question, because they knew he was in it with them to the death.

The same goes for Kieran McGeeney in Armagh. When they visit the hospitals and the schools and the old people’s homes, it is not mere virtue signalling. Kieran’s obsession with the boys is not just as footballers, but as men. An Armagh icon, they adore him. But most importantly, they trust him. This is because their loyalty to each other is absolute. When he talks about Armagh and the great importance to the community of what the team is doing, it is not empty talk.

It is deeply and honestly meant. He is stitched into the county and its people, as they are. This real loyalty is the indispensable quality, since winning an All-Ireland is a cause that obliterates every other part of your life. It is a cause that is easy to weary from. A cause that can feel too much. A cause were people must do extraordinary things for reasons that are not exactly clear. A cause which is doomed unless everyone is in it together.

This is the undeniable truth. There have been 11 Ulster All-Ireland senior football champions in the modern era, starting with Down in 1991 and ending with Armagh in 2024. All 11 have been managed by a manager from the winning county. Pete McGrath (Down), Brian McEniff (Donegal), Eamonn Coleman (Derry), Joe Kernan (Armagh), Mickey Harte (Tyrone), Jimmy McGuinness (Donegal), Feargal Logan and Brian Dooher (Tyrone) and Kieran McGeeney (Armagh).

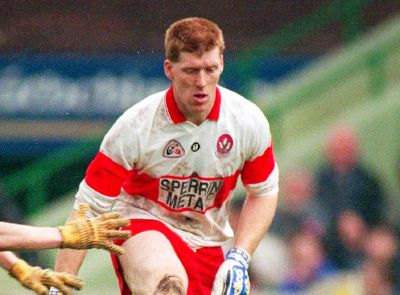

This is because to win, to play with honour, we must be loyal to each other. We used to have that in Derry. Brian McGilligan chasing back frantically to lay a big hit on Greg Blaney as he powered through for what looked a certain goal. Anthony Tohill ignoring all signs of human weakness. Enda Gormley playing his best football after two ACL tears which were never repaired and he had been told he would never play again, going on to win two All-Stars and an All-Ireland.

In that 1993 final, Gormley was poleaxed early on by a heavy off the ball punch from the fearsome Niall Cahalane. His response? He went on to give his greatest ever performance, kicking two incredible points from play and nailing every single free. Scullion? An animal. Kieran McKeever? The greatest character I have ever played with or seen on a sporting field. For McKeever (or ‘Fever’ as we called him), there was no such thing as injury. Or Sean Marty Lockhart, or Fergal Doherty, or Enda Muldoon or any of them. In those days, Derry Gaelic football was about heart and soul. About who we were. And nothing is more important than that, win or lose.

I have nothing against Paddy Tally, but he should have more self respect. The Derry board has traded away any hope of an All-Ireland. More importantly, they have traded away our honour and integrity, and without that, Gaelic football is as soulless as soccer.

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere