Sunday brings the latest chapter in the age old Derry and Tyrone rivalry. Former players Declan Bateson and Jody Gormley recall some of their memories.

By Michael McMullan

GROWING up, all Jody Gormley wanted to do was play for Trillick, a parish rich in tradition and hugging the Fermanagh border.

A chapel and a GAA club was all there was in an area where football was everything. If he was lucky enough to play for Tyrone, that would be the icing on the cake.

Injury kept him out of county minor trials, but rubbing shoulders with the cream of Ulster at university level helped him blossom into a two-time All-Ireland U-21 winner.

Drafted into the Tyrone senior panel at the heel of 1994, he made his championship debut the following summer just eight miles from home with victory over Fermanagh in Irvinestown.

It was an era when Tyrone folk looked on with envy at Down and Derry lifting Sam.

Derry were league champions and after filleting Armagh in the championship were eying a second All-Ireland.

An Indian summer struck Ireland in 1995. Moulded boots, the fast ball and an electric atmosphere hugged that championship season. It was white heat at its purest.

With the Ulster semi-final poised at 0-10 each, Stephen Lawn kept the ball on the sideline before speeding goalwards. His raw pace singed Derry’s defence until three red jerseys boxed him away from goal. Jody Gormley peeled off on the outside before his left boot edged Tyrone into the lead and a memorable victory.

“It was the best point I ever scored in Clones…from 14 yards,” Gormley utters with a smile on what was a hammer blow to a Derry team in their prime.

“Derry were public enemy number one in Tyrone and we fed into that…they were always the team to beat.”

There was jealousy factored in from their neighbours bringing home Gaelic football’s most cherished silver.

Declan Bateson hails from the footballing hotbed of Ballinderry, on the shoulders of the Tyrone border. On the other side, Ardboe and Moortown both sweep down to the shores of Lough Neagh.

He remembers the rivalry going back to the mid-eighties and Tyrone almost chinning the Kerry golden generation in the All-Ireland final, with Derry crowned kings of Ulster 12 months later.

Jody Gormley chips into the conversation, asking if Bateson was supporting their Ulster rivals.

“I would say that in Ballinderry, more than half were Tyrone supporters anyway,” Bateson admits.

For the rest, himself included, they’d be clapping scores on the outside, while deep inside there may not have been the same conviction.

On the pitch, it was dog eat dog with no quarter asked or given. Away from football, Bateson and Gormley both spoke of respect.

Bateson and Tyrone defender Fay Devlin shared the same bus to school in Magherafelt. When Ballinderry and Ardboe played underage challenge games, it added to the familiarity.

“The two Lawns (Chris and Stephen) were great lads. You’d have met them and had the craic,” said Bateson who always had Fay Devlin as a marker in Tyrone games.

“I was never afraid going into a game with Tyrone and marking Fay. I knew it was just going to be a football battle to see who’d come out on top,” he said.

Jody Gormley built up great relationships with Derry players with in the colours of UUJ and on the Queens’ teams they came up against.

He recalls meeting Anthony Tohill in a hostelry after Derry had won the All-Ireland. Jody passed comment how his uncle Jim – a Tyrone man living in Coleraine – was terminally ill with cancer in his early forties and how great it be for him to get a glimpse of the Sam Maguire.

Tohill was at Gormley’s door the next morning and plans were hatched to make it happen.

“Even though there was a rivalry there, there was a lot of respect,” Jody stressed. “He brought the Sam Maguire to my uncle a few weeks before he passed away. He couldn’t believe it when big Anthony walked into the house. It gave him a lift and you should’ve saw the head on him…even though he was a Tyrone man.”

That was the Derry and Tyrone rivalry in a nutshell, but when the championship heat was on full blast, there were few occasions to match it.

Declan Bateson came into the u-21 grade after helping Derry win the minor All-Ireland, but Jody Gormley’s Tyrone group were top dogs. With Eamonn Coleman coming on board, Derry swayed the momentum back at senior level.

With minutes remaining in the 1992 league final, Peter Canavan’s goal had Tyrone 1-8 to 0-8 ahead when the ball landed in the arms of Bateson at the foot of Hill 16. With goal written all over the chance, Finbarr McConnell’s trailing leg blocked the shot at the expense of an Anthony Tohill ‘45’ that sailed between the hands of Plunkett Donaghy and into the net. Tohill and Dermot Heaney tagged on points to clinch victory against the run of play.

The sides were to meet in the first round of the championship and Derry’s below par performance was all over the media. It was right up Eamonn Coleman’s street.

“He got stuck into us in the next two weeks,” Bateson remembers.

With Coleman living so close to Ballinderry and county border, he fully appreciated the rivalry.

“In later years, managers like big Brian (Mullins) didn’t get how incestuous the Derry and Tyrone thing was,” Bateson continued.

He explained how Mullins billed Dublin’s meetings with Meath as another routine game in the season.

“You can’t say that…it is not another game,” Bateson argues.

“They (Tyrone) had us in the crosshairs and Eamonn understood it. From knowing lots of people in the Moortown and Ardboe area and having the craic with them he understood the level of hatred there was between the both sets of supporters and players and how important it was to win.”

In the weeks before the 1992 championship, video footage was used to fire up Kieran McKeever on how much room Peter Canavan was afforded for his league final goal.

A newspaper article on the back of the Celtic Park dressing room door questioning Tony Scullion’s ability to pick up Mattie McGleenan took the focus to another level. Coleman was a master at pusing the right button.

“There was a big circle and Scullion’s name on it,” Bateson points out. “Scullion never got to see it. It was crumpled up and there could’ve been anything written on it. Eamonn took a bit of licence with what was said.”

It was another ingredient that had the Derry team almost taking the dressing room door off by the hinges and when Dermot Heaney hit an early goal, they cruised to victory in a style greater than the winning margin.

“They got waited in the long grass and got us back,” said Bateson.

If 1992 and building towards winning an All-Ireland was Derry’s magical spell, their neighbours across the Sperrins were getting restless.

Derry lost their All-Ireland title in the first round, with Eamonn Coleman controversially sacked.

Tyrone were on the wrong end of an Ulster final hammering at the hands of a Down team on their way to the 1994 All-Ireland.

With the changing of the guard, Jody Gormley was part of the new beginning back-boned by their all-conquering u-21 winning teams.

“I don’t think there was any sense of pressure,” Gormley offers. “It was a case of if Derry and Down could do it, then why not Tyrone.

“We would’ve felt we had a good enough squad. The boys were ambitious and the training was brutal under Eugene (McKenna) and big Art (McRory). It was tough stuff and everyone was up for it.”

Despite their youthful march, there was the bravery to “go at” anybody.

“The view was that at some point we were going to catch up with Derry, our main rivals. We thought we were as good as them, but we had to go out and prove it.”

By the time Tyrone emerged against Fermanagh, they knew Derry – fresh from a 10-point win over Armagh – were the acid test.

“I don’t think there is a better feeling than standing in the middle of a packed championship match and everybody is up for it and you’re listening to Amhrán na bhFiann,” Gormley said of their pre-match preparations. While the game was “a blur”, he knew they were ready.

“I can distinctly remember standing there, ready to go and knowing you are in peak fitness, looking around and feeling honoured to have the opportunity of playing there.”

By half time, Pascal Canavan and Seamus McCallan had been sent off, with Derry 0-8 to 0-5 ahead.

Gormley describes the scene in the Tyrone dressing room as “bedlam” and while Art McRory was down the narrow dressing corridor giving referee Tommy McDermott “a bit of advice”, psychologist Dr John Kremer was holding court in the Tyrone dressing room.

“He came in and settled everything down,” Gormley explains. “We gained a bit of composure and there was a general feeling that he’d (the referee) level things out a bit and we’d throw everything at it.”

Going down to 13 men “galvanised” Tyrone and the sense of injustice was turned on its head as they threw the kitchen sink at the second half.

Declan Bateson also used “bedlam” to describe the scene in the Derry dressing room. Hardly fit to walk from an ankle injury, Bateson was getting strapped up by physio Sean Moran.

Team doctor Ben Glancy was stitching Damian Barton’s eye, who “didn’t flinch” as the needle snaked in an out across his forehead. While Glancy asked about his welfare, Barton impatiently insisted on getting patched up quickly for a return to battle.

“He (Barton) had Pascal (Canavan) by the throat and Pascal hit him two or three fantastic blows and opened Damian right above the eye,” Bateson vividly remembers of the incident before half time that saw Canavan sent off.

“We had won the league with 80 different players used because there was a strike at the start of the year,” Bateson points out of the spell when several players walked away, on strike, when Mickey Moran took over after the sacking of Coleman.

The season was one of uncertainty. After not being tested against Armagh they were in the eye of a Tyrone second-half storm under the unrelenting summer sun.

“When you are not tested in games then you think everything you are doing in games is right and it’s only in hindsight when are tested and you fail that you realise you weren’t right,” he said.

Derry were three points ahead with two extra men. The management’s message was one of discipline and not getting sucked into the battle.

Bateson still feels that under Coleman’s watch the more favourable approach would have been “one in, all in” at the first sign of an early second-half melee given Derry’s “bigger, physical team” and it would’ve been a test of Tyrone’s underbelly.

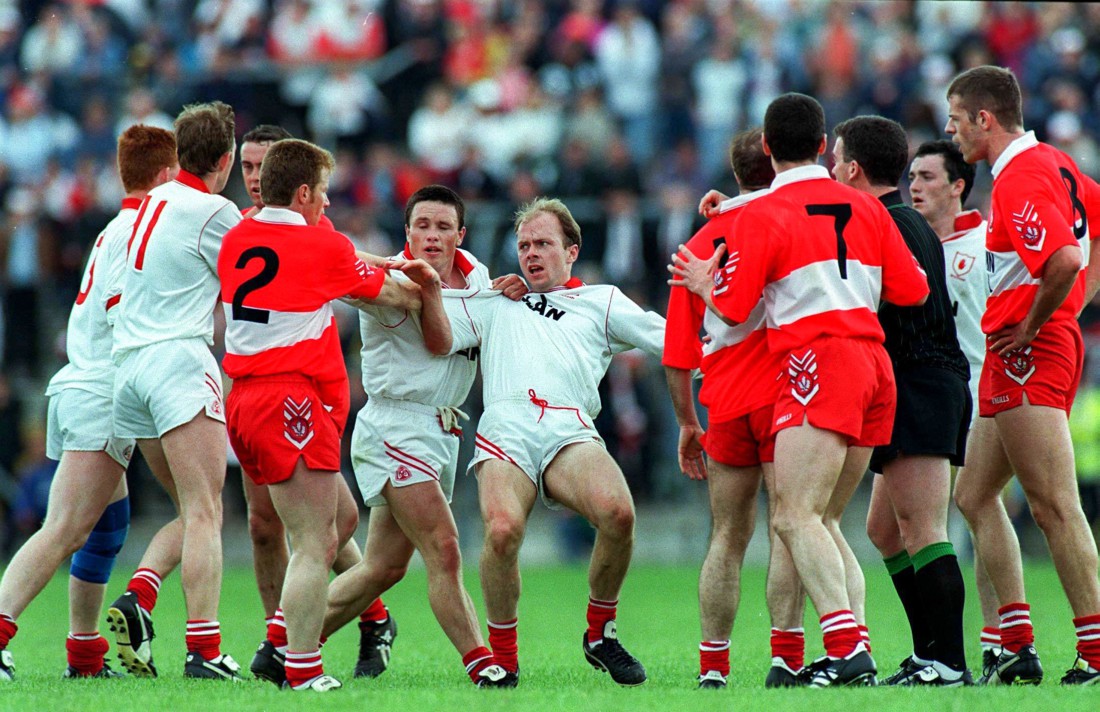

“It was the most intense atmosphere I ever played in,” Bateson said. “Clones was packed. I would nearly go as far as to say that, at times, the atmosphere was ugly with the different sets of supporters, there were a few fall outs.

“I think that sometimes, when a 30-man all in thing happens and they go back to their positions, that’s it…that energy goes out of the game and people go on and play the football,” Bateson said.

Instead, Derry played within themselves; Tyrone got a foothold and Fergal P McCusker was sent off to even up matters. Three Peter Canavan points in ten minutes levelled matters.

“You could see the game slipping from us; you could see us losing all the key battles,” Bateson adds.

Enda Gormley did put Derry 0-10 to 0-9 ahead going into the final quarter, but Canavan tied the game before Jody Gormley’s winner.

Tyrone went all the way to September and lost a controversial All-Ireland final to Dublin. Looking back, Jody feels pouring everything into the Derry victory came at a cost. They never looked any further ahead.

“When we beat Derry, there was complete euphoria and people still talk about that game. At that stage, for us, it was as big as winning an All-Ireland, but it shouldn’t have been.

“Looking back at it now, but that was the pinnacle to get over Derry that day, particularly in the manner of the match the way it panned out.”

Tyrone accounted for Derry the following season on their way to retaining the Anglo Celt Cup.

Derry got their revenge in a 1997 hammering in the semi-final, but lost the final to Cavan before winning the county’s last Ulster senior title 12 months later.

Declan Bateson likes the direction current Rory Gallagher has taken Derry, but feels the rivalry is a shadow of what it was.

“That’s because Derry have slowly dwindled and Tyrone have maintained their high standards,” he said.

Sunday brings the latest installment of a GAA story etched into history, ready for the next twist in the tale. We’ll have to wait and see how it unfolds.

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere