Anthony McGurk was Derry’s first All-Star, was on their back-to-back Ulster winning team of 1976, won an All-Ireland Club with Lavey and was a founder member of Steelstown. Michael McMullan went to meet him…

WHERE do you start with Anthony McGurk? It’s a book you need, not a feature interview.

The two All-Stars, at either side of the mantlepiece, suggest you are in the company of greatness.

Seated in his living room, he speaks calmly and – while not claiming to have a great memory – the detail flows with ease and well into second hour of a conversation that skates across different eras.

Time flies. As the conversation comes to an end, he puts on his modest hat. Despite a plethora of milestones across life, work and sport, McGurk sells himself massively short.

“I had no natural talent, I wasn’t a good footballer,” he said. “I could concentrate and I took it seriously.”

Those he played with had more in the locker. They had a better catch and would score more.

Is he being too modest? No. And McGurk is quite confident in his answer.

This writer points to the 1973 All-Star won as a forward, backed up another in defence two years later.

“I had determination and ability to concentrate if I was marking somebody,” he offers of his. “There were miles better people than me that I played with.”

A direct opponent needed marked until he was out of the game and it was time to hone in on another threat.

“I always tried to get the first ball and if I didn’t, I would get the second ball and go on a run,” McGurk said. “It meant that somebody was looking after me, even though I was the back. You tried to get on the front foot and I had the ability to concentrate.”

If a goal was conceded, it was in the past and could be reflected on later for ways to improve. But in the game, it was about the next ball.

“In terms of skills….my brother John had acres more skill than I had, Colm had acres more skill and Hugh Martin would’ve been way, way better players,” McGurk modestly adds.

He is still selling himself short. Three Ulster senior titles. An All-Ireland Club with Lavey in the twilight of his career, getting 10 or 15 minutes before game-changers were invented. London Tir Chonaill Gaels had them boxed into a corner that McGurk’s goal pulled them out of.

There was an All-Ireland u-21 medal. Add in Corn na nÓg and MacRory Cup medals with St Columb’s, Derry. He was one of the best players of his generation at Queen’s with a Sigerson Cup medal and a place on the Combined University team to prove it.

If he had the time, he could’ve pushed on in both soccer and rugby. Coleraine floated the idea of a few Steel and Sons games on the wing. City Of Derry saw enough in his skillset to ask him to swap the a round ball for the oval variety even though he was touching 40.

In the days before penning this piece, one mention of the name Anthony McGurk to former classmate, Derry chairman and GAA aficionado Sean Bradley prompts a succinct response. McGurk was one of the greatest players ever to play for the county. Debate over.

***

Hugh A McGurk played on Lavey’s first senior football championship winning team in 1938 and on their maiden hurling success two years later.

He was involved in all things GAA, from playing to committee rooms to being in Derry’s management team that steered the county to the 1958 All-Ireland final.

After marrying Catherine Bradley, a Desertmartin camog from a musical family in Tobermore, they had 13 children together. From Anthony, the oldest, the McGurks were steps of stairs all the way to Ciaran, two decades his junior.

THE CLAN…Anthony McGurk (front left) pictured with his seven brothers

“We had a small farm with pigs, cattle and hens.” Anthony remembers. His father started a shop and later petrol pumps.

“That was to raise us and we were probably the best customers in the shop and ate what we could.”

In the early days, Anthony was righted footed and he remembers his father producing a plastic ball around the age of three and insisting he shape with the other foot. Even to a point, he’d hold his son’s right leg.

And it paid off. While admitting to not being “massively accurate” there was comfort kicking off both feet as he made his way in football.

He’d enough to throw a dummy onto the left to navigate him out of a tight spot and to slot in at centre-back with the field opening us as his playground in front of him.

Anthony passed the 11-plus a year early and Master Fay encouraged him to “stay about” Mayogall Priamry School and take the entrance exam for St Columb’s, Derry the following year. He was more than capable.

It helped him on his way to a Civil Engineering degree and later roles as Town Clerk and Chief Executive of Derry City Council.

Looking back now, he’s not an advocate of boarding school. Children need their families at that age and while not having a “particularly” hard time, there was a tough love element. There would duckings or, in the depth of night, the odd clip with bar of soap in a swinging sock.

“I wouldn’t crucify it but I wouldn’t send any of my kids to it,” McGurk said.

Aside from getting home at end of each term, senior school brought the luxury of a few hours up the town to the cinema or chip shop if there was a surplus few bob.

“It was the first time I did serious training,” McGurk said of Fr Iggy McQuillan’s introduction of weights.

“Our boys at home said if it wasn’t for it, I’d be the same size as them. They joke that I was the oldest and got well fed.”

Fr Iggy incorporated many of the training methods of athletics. When the school bell tolled at half three, there was a slot for football with five hours of study until ten o’clock.

St Columb’s senior team were MacRory and Hogan Cup champions in 1965. McGurk, a Corn na nÓg winner, played on their MacRory winning team of the following saeason as a fifth year.

With underage club football limited in those days, St Columb’s was an excellent pathway to a highly decorated career. It was the days before St Patrick’s, Maghera’s existence.

“My own career changed for one reason, going to Queen’s and discovering contact lenses,” McGurk said, explaining how short-sightedness hindered his reaction.

It was fine while glasses were permitted. Without them, it was nearly impossible to play. Especially in carnival games, often played in the fading light.

“I had to ask who had the ball or who scored or if the play was going in a certain direction…I had very poor eyesight,” he said.

Spending a third of his first student grant of £120 on a pair of contact lenses was money well spent

“I kept wearing them for three days, even though my eyes were watering, so I would get used to them,” he added. “It made a massive difference to my football and my life in general.”

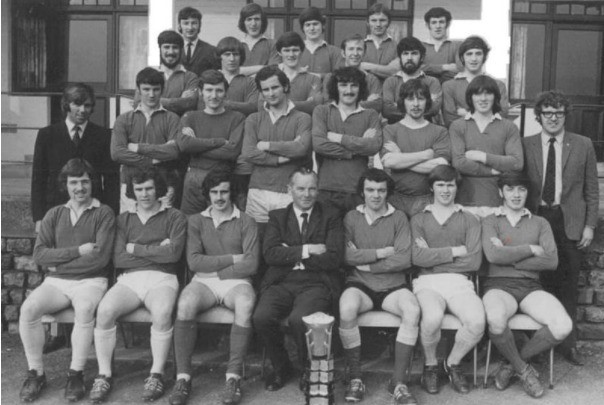

COLLEGE LIFE…Anthony McGurk won a Sigerson Cup with QUB, his pictured on the far right of the third row

McGurk was in his final year of minor when the call came to join up with Derry’s 1968 All-Ireland u-21 squad as his stock began to grow.

After a few years on the fringes of the senior team, he came on for the injured Malachy McAfee in the early stages of the 1970 Ulster final win over Antrim.

While Derry would lift the Anglo Celt Cup again in the 1975 and 1976 seasons, McGurk speaks of how the early 1970s were “wasted years” with a team that should’ve been challenging for Sam Maguire.

“I think Derry had the potential then to win three or four Ulsters, if not All-Irelands,” he said. “Offaly won an All-Ireland (1971) they were the team we beat in the u-21 final.”

By the middle of the decade, the all-conquering Kerry team were in their pomp with the Dubs also in the mix.

Derry were able to hold their own with the best Ireland had to offer in the league, but the championship was different and – like the present day – getting out of Ulster was a battle in itself.

There were the remnants of Down’s trailblazers of the sixties. Cavan were always also in the equation and Donegal came along to take a title.

At that time, Derry travelled to England for the Wembley tournament involving all four All-Ireland semi-finalists.

“We had no problem winning it,” McGurk said of a weekend that saw Saturday’s semi-final played under the famed ‘Twin Towers’ before heading to London GAA’s hub in New Eltham for the final the following day.

One of the building blocks for Derry’s All-Ireland success of 1993 was the belief taken from Down and Donegal successes in the years before it.

From conversations with former great Sean O’Neill, McGurk recalls him talking about how Down always believed in themselves. Once success arrived, it almost squeezed an opponent into oblivion before they’d made even the first move.

“It is about confidence and you need one win to bring you on,” McGurk said.

After winning Ulster in 1975, the Oakleafers retained it the following year with McGurk named as Man of the Match in both the drawn and replayed finals with Cavan.

The problem is keeping a level head, somewhere between confidence and expectation. This is where McGurk felt Derry fell in 1977, with their best chance of challenging for Sam.

In the All-Ireland semi-final cycle, the Dublin and Kerry teams they fell to in previous season were on side of the draw with Ulster paired with whoever emerged from Connacht.

Derry jumped the gun by not showing Armagh enough respect ahead of the Ulster final and came a cropper to a team they’d beaten by 15 points the previous season.

“We should’ve won in 1977 against that Armagh team. They won’t like it or won’t agree with me, but we were far too confident,” McGurk admitted.

“Boys went to America and we said we’d bring them back for the All-Ireland semi-final…not the Ulster final.”

***

Winning an All-Star in two different positions is a mark of both consistency and flexibility. Being able to kick off both feet was a help.

McGurk didn’t care where be played. If Derry needed a half-back, he’d answer the call. It was the same in attack.

“I was in midfield with Laurence Diamond for a while as well,” he said. “The first All-Star, I got it at corner-forward and never should’ve got it anyway.”

It was the days of limited television coverage and many of the journalists from the selection committee rarely set foot inside Ulster. McGurk’s case was helped with a fine performance when he travelled as a replacement All-Star the previous year. It helped get him noticed.

“The Ulster journalists would’ve punted for three or four players and it wasn’t about positions. They’d have slotted you in somewhere,” was his take on the selection process.

The second All-Star came at centre-back in 1976, with Peter Stevenson and Gerry McElhinney also listed from a Derry team who were at the peak of their powers.

Derry’s training all came under the watch of manager Frankie Kearney who had Sean O’Connell on board to assist. O’Connell did mix training with playing full-forward in the 1975 season at the age of 38 before calling time before the 1976 championship.

Kearney brought organisation in everything attached to the setup. Training was a regimented Tuesday and Thursday with a game at the weekend.

Later in the tenure, a Saturday kickaround was brought in with a chat on any of the plans being hatched for game day. When it came to logistics and travel arrangements, everybody knew where they had to be and when.

“It was more organised and training was that bit tougher,” McGurk said. There was an advance from the older days of laps, sprints and backs against forwards, followed by more laps to finish.

It was the days of running up and down the banks at the side of Ballinascreen’s Dean McGlinchey Park with a teammate on your back. And back down again.

“We started to go to the sand hills in Portstewart, running up and down there and did a lot of work on sand,” he added, explaining about how it was taken from the training methods of middle-distance Olympians such as Peter Snell to help acceleration through shorter steps.

One of the regrets was trying to come back from injury too early. A pulled hamstring before a league final with Dublin lingered on.

“I just wanted to play and was happy to get strapped up,” McGurk said. “I was probably one of the first players to get an injection to play and that wasn’t the right thing.

“From that to I finished with Lavey, I wore a big blue bandage, because I was susceptible to hamstring tears.”

There was no reverse gear in the off-season. He’d line out alongside Laurence Diamond and John Brennan for a Rainey recreational rugby team. There was no training, just a match. It was the same with soccer. It would keep the body ticking over under planet GAA came calling again.

***

An 11-year-old Anthony McGurk was minding his own business, kicking about with his own ball as Lavey hosted Glen in a minor game.

It was the days of one ball and when it got burst in the hedge the game was in jeopardy.

“They came looking my ball,” McGurk recalls, saying how he refused at first. Then came the deal. If he handed over his ball, he’d get a game. Deal. In he went.

And so, a Lavey career began, one that would end with the Andy Merrigan Cup in Croke Park on St Patrick’s Day 1991.

“I played a bit of schoolboy football, but it was very little and not organised like it is now. Most days there were teams not turning up,” McGurk said of his underage memories.

“There is a picture of the team I played on and there were 12 different colours of jersey, socks, togs and different colours of everything.”

Within three years, he made his senior debut against Ballinascreen on the strength of word filtering back about his performances for St Columb’s in the Corn na nÓg success.

“Wee Tommy Doherty never let me forget it, he was right-back for Derry in 1958 and was getting on in his career and was playing corner-forward,”

“They put me on in wee Tommy’s place and he was a sub. He reminded me years later that I took his place in my first game.”

It turned full circle in 1991. Anthony was hanging up his Lavey jersey for the last time with Tommy’s sons Thomas and Damian coming into the fold.

By the end of the sixties Lavey and Glenullin were vying for promotion to the senior ranks. A youthful Lavey made the climb and held their own in the league.

They reached the 1971 county final only to come out on the wrong end of “an awful hammering” at the hands of Bellaghy.

Lavey stayed at the top and were back in another final six years later when Joe Boyle’s goal saw off Ballinderry to take the title.

McGurk added a second senior medal in 1988 with a new-look team came through on the back of underage success.

With kids growing up, living in Derry and working in Omagh wasn’t a great mix for trying to factor in Lavey training into the weekly schedule. He informed John Brennan that a bit of reserve football would be his lot.

Fate arrived in the 1990 season when work took McGurk to Belfast. He’d arranged to stay with his brother Hugh Martin to save the 150-mile round trip a couple of evenings a week.

“He was going up and down from Belfast to training,” Anthony said. “I did a bit of running around the pitch to keep myself in shape. I was finished well before they were and went down to see my mother and father.”

Brendan Convery was the new Lavey manager. On the nights he was short a few bodies, he cajoled Anthony to play in the training matches.

“Go on in there ‘Gurky’ and worry Anthony Scullion and give them a bit of exercise,” McGurk said. “It was easy for me, those boys were running around the field and doing sprints, so I was looking good compared to them so I started to play then.”

The stall was laid out. McGurk had zero interest in taking any young lad’s place on the team but injuries opened the door for some league action.

Convery was a “persuasive character” and Anthony McGurk had his arm twisted and he agreed to hang around.

CROKER TIME…Anthony McGurk celebrates Lavey’s 1991 All-Ireland

“That year, boys knew when I came on there were 10 or 15 minutes to go. They could nearly set their clocks and it was a matter of holding out in these matches.”

That’s how he came to have an All-Ireland Club medal. It was more by fluke than by design.

And Lavey will be forever grateful for his input. When London champions Tir Chonaill Gaels, a team littered with county stars, put them to the pin of their collar in the quarter-final, it was McGurk’s fluke goal that saved their bacon.

After seeing off Thomas Davis in the semi-final, Lavey’s dream was complete when they saw off Salthill to land the biggest prize in club football.

***

Four years before calling time on his Lavey career, Anthony and his wife Mary were among the founder members of the Steelstown club.

Their sons Maurice, Brian and Conor needed an outlet for Gaelic games. Philip Devlin and his wife Marion (Drumsurn) and Mickey Doherty from Claudy were also part of the new beginning.

It began with u-12 and u-14 with players drifting away to other clubs to pursue their career.

Some played with Doire Colmcille who asked Anthony to get involved in the running of the team.

Then, after some thought, there was a concerted effort to see could they form older teams within Steelstown and the momentum picked up.

“That was another reason I stopped with Lavey…I was out nearly every night of the week,” McGurk said of the time involved in making the trek down from the city.

The next step was an idea to start a senior team. Fermanagh natives Kevin Cassidy and Ciaran McBrien were now living in the city and McGurk took up the invitation to train the team.

“There was Tom McGuinness, Terry Moore, Jude Hargan, Paddy Cosgrove and a crowd of boys that were 40 something. We started playing over 40s tournaments at club carnivals,” McGurk said of their early days.

“We took the team down to play in Ederney and in various Tyrone tournaments. We said we’d give it a year.”

McGurk can still remember their first outing, an away game against Swatragh Thirds.

“A man from Swatragh, who I will not name, said “McGurk landed with this pile of doctors and solicitors…they’ll last a year.”

“I eventually got Tom (McGuinness) to take over the senior team and he brought great enthusiasm to it. We worked the young boys up into it and we had a very good committee going.

“There was a lot of interest, we kept it going and they are going very well at the minute.”

Progress came in the form of underage teams competing in the A grade. Current chairman Paul O’Hea and Martin Dunne won All-Ireland Minor medals with Derry in 2002.

Five years later, Neil Forester, Stephen Cleary and Mickey McKinney lost a minor final to Galway.

From that age group, Kevin Lindsay and Ryan Devine were also on the club’s All-Ireland intermediate winning team two years ago. Outside of a bit of coaching at underage, McGurk takes no credit for their All-Ireland success.

“Paddy Campbell and me looked after the senior team for a while and he is now back with the seniors,” McGurk sums up.

MEN OF STEEL…Anthony McGurk and Steelstown captain Neil Forester celebrate their All-Ireland intermediate title

***

McGurk’s other managerial chapter came when he had a visit from Brian Mullins when he was sounded out about managing Derry after Mickey Moran stepped away in 1995.

Mullins told the county board he’d take the gig if Anthony came on board. It was after the something he hadn’t much interest in.

“He (Mullins) was persuasive and I said I would do it for one year and we were there for three,” McGurk said of a stint that yielded a league title in the first season.

It was a management team that included McGurk’s former manager Frankie Kearney. The 1997 campaign ended in a controversial Ulster final defeat at the hands of Cavan followed by a step further 12 months later.

McGurk got more than he bargained for in Mullins’ first game in charge, away to Sligo as part of a bonding weekend before the panel was finalised. When the one goalkeeper in the panel “19 or 20” players got injured, McGurk got the call.

“Mullins told me to go into goals and I ended up playing in goals for Derry in 1996, it was my last game for Derry aged 47,” McGurk laughs.

In terms of the tenure, he regrets the county not adding to the 1993 visit of Sam Maguire.

“It was a disappointing time because that team was good enough to have won more than one All-Ireland,” McGurk said, placing the 1997 campaign with 1977 when complacently set into the camp.

The final defeat to Cavan had a Breffni ‘point’ what was clearly wide. There was also a double bounce in a game of margins, but McGurk points to the body language on the morning of the game.

“That was déjà vu, it was 1977 revisited it,” he said. At the pre-game base in an Enniskillen hotel, there was too much laughing. There wasn’t the steely focus.

There was also a visit to the Connacht final to watch Galway struggle to see off Roscommon after extra-time in a replay thanks to a goalkeeping error from Rossie ‘keeper Derek Thompson.

“We were lucky enough to beat Donegal but went to see Galway and Roscommon, it was a bad match and both teams looked poor. We should’ve known better after ’77, Kearney and me both there, but we were confident we could beat them.”

Regardless of what is said in a dressing room, once the wrong vibe is rooted it’s hard to change the focus.

Is there a bit that eats away having not having the one medal everyone craves? Getting hands on Sam Maguire is everybody’s Everest.

“I have no regrets,” McGurk sums up. “I would’ve loved to have won an All-Ireland, but I am a very lucky person in football and every way.

“I won an All-Ireland u-21, I won Sigerson, I won Railway Cup medals, I won an All-Ireland Club. I have three (Derry) championships; I am luckier than a lot of other players.”

After his retirement from the world of work in 2008, Anthony and Mary were over and back to Spain where they eventually relocated eight years later.

Anthony had a stroke in 2019 and needed a second operation, open heart surgery, the following February. With the outbreak of Covid, Spain wasn’t the safest place and back to Ireland they came.

Looking at and chatting with him now, you couldn’t tell. At the recent Ulster final, McGurk was introduced to the crowd as part of the management team of the 1998 Ulster champions.

Now he watches on. The modern football isn’t easy on the eye, but he could picture a younger version of Anthony McGurk fitting in. One in his twenties.

The sight of Ethan Rafferty spraying passes is something he could offer. With the ability to dink balls off both feet, the freedom of teams dropping off would give him the canvass.

Hugh A McGurk was spot on all those years ago. A man who can kick with two feet can go anywhere.

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere