Sean Marty Lockhart was one of the greatest defenders in the game and holds the record number of International Rules’ appearances. Michael McMullan went to meet him…

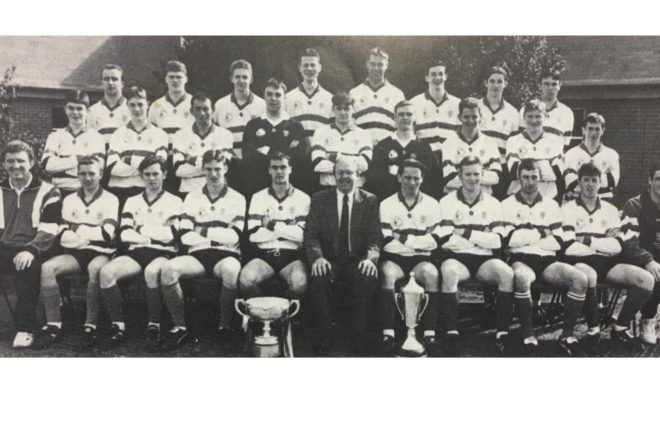

NOBODY else has played 16 times for Ireland in the International Rules. Not everybody picks up an All-Star, Ulster and League medals in a 15-year inter-county career. Not everybody wins an All-Ireland u-21 medal. Not everybody wins a MacRory Cup as a player, then as captain and later as coach – all with St Patrick’s Maghera. Not everybody is Sean Marty Lockhart.

Humble. It’s a word that sums him up better than anything else. Away from the arena he prepared diligently for, he was quiet. There are no airs or graces. But when he is on, he’s on. And totally switched on.

When told he was picking up Peter Canavan in the 2001 Ulster Championship opener, Lockhart spent a staggering 22 hours, on top of team training, studying the Tyrone ace’s magic and more importantly what Canavan did when the size five was not in his grasp.

But every opponent got the same level of respect. On a Saturday morning, early in 1995, in Moortown, he was hunkered under a dressing room sink with a prayer in his hand minutes before the ball was threw in on a double-scores MacRory Cup quarter-final win over St Macartan’s, Monaghan.

As captain, it was Lockhart’s fourth season on the panel. An icon – not by his admission – of the Ulster Colleges scene with three All-Stars (two hurling and one football) keeping his MacRory and Mageean Cup medals company. But in that moment of quiet time, St Macartan’s were getting his full focus in a season when nobody came close to ousting Maghera on the way to glory.

Perched at the boardroom table in the school where he now teaches, Lockhart hasn’t changed one iota. The voice is soft. The words are well chosen. If you didn’t know him, you wouldn’t fathom the magnitude of his career.

When you start to dig, you quickly realise how much of an example he is to any budding defender looking for a leg up in their journey to the top.

When sport arrived first in his life, it wasn’t GAA. It was boxing. And any glance at his footwork on the playing fields of Ulster and beyond tells you of its benefit. Those short steps, going left and right with precision as he watched on at an attacker’s midriff, checking out his movement waiting for the time to pounce.

“I was seven or eight and I boxed for a couple of years in a place over beside Banagher chapel,” Lockhart recalls.

“The first night you are there, you’re into the ring against a boy maybe two years older than you and you can imagine what that would be like; you’d get your head beat in.”

It was the days before Go Games when football and hurling didn’t begin until u-12s, but Liam and Willie McLaughlin put them through their paces. With the punch bags and skipping ropes came discipline.

Too young to compete, he stuck with boxing long enough until Banagher’s underage began.

Lockhart remains forever grateful for all the guidance he received from all quarters. From the u-12 days under Sean ‘Roe’ McCloskey, he went on to pick up three minor hurling titles and later was wing-back on their 2005 senior winning team.

“When I was P6 or P7, our u-14s got to the county final,” Lockhart remembers of his early football exploits.

“David Hassan, who would’ve played in goals for Derry…it was his team and I was maybe number 32 (on the panel) but the journey was good.

“We had a decent group (at his own age)…the likes of Danny McGrellis, Richie O’Kane, Gary Biggs and Ronan McCullagh.”

After winning the North Derry A u-14 Championship, Banagher were beaten by Ballinderry in the All-County final.

Banagher has always been able to churn out county players despite a modest pick at underage. There are 110 pupils on the roll in St Canice’s Primary School in Feeny, with many from neighbouring Altinure school going on to wear the green and white of Craigbane.

“It’s phenomenal when you think of the players that came through our club,” Lockhart said.

He looks back ten years when Banagher pushed a Ballinderry team, who were on their way to the top of the tree in Ulster, all the way in a championship semi-final.

“We had boys in their thirties, boys in the mid-twenties and early twenties in that team,” he said.

Below his own age was an u-16 winning team of 2002 with a 14-year-old Mark Lynch to the fore, followed up by an u-14 winning team from two years later that had former Everton and Republic of Ireland soccer star Eunan O’Kane on board before his move across the water.

It has turned around again with another emphasis on underage development with the club’s new indoor training venue at its core.

Another of Lockhart’s qualities was his insatiable desire to learn. All this coaches, at club and in school, offered something different and he sucked up every nugget.

Despite needing an inhaler to control the wheeze from his teenage asthma, he always excelled in long-distance runs, but his quick feet were only taking him so far towards the twisting and turning needed for the unforgiving environment of inter-county football.

It was his thirst for knowledge and strong observation skills that took him to the next level. The penny dropped in his first year as a starter on the MacRory team. Paired with Enda McQuillan, two years his senior, for a crisscross passing drill, Lockhart would stop at the cone for a nanosecond before adjusting his body weight to go the other way.

“Enda glided around the cone,” remembers Lockhart, who was corner-back on the team. “I was thinking I couldn’t stay with this boy, so I copied him.”

Captain Colin McEldowney, Kevin Ryan and Eamonn Turner were the other speed demons.

“Co (McEldowney) had a low centre of gravity, he always ran to a line and out of it like a rabbit… his turn was lethal,” Lockhart said about the days when he began to take his game to another level.

Maghera were beaten in the final by a St Colman’s team – led by star man Diarmuid Marsden – on their way to the 1993 Hogan Cup.

The same year, Lockhart had his first taste of county football with the minors. After coming out on top in his battle with current Cavan manager Mickey Graham, Derry were beaten on that infamous wet Sunday in Clones when Brian Dooher and Gerard Cavlan led Mickey Harte to his first trophy as a Tyrone manager.

The following year Lockhart was full-back on the MacRory winning team who went all the way to the Hogan Cup final where they were on the wrong end of a hammering by St Jarlath’s, probably the greatest team in the history of the competition.

Michael Donnellan, Tommy and Pádraic Joyce, John Divilly, Tomás and Declan Meehan went on to win All-Ireland medals with Galway. Corner-forward Derek Reilly played on Corofin’s first All-Ireland winning side within four years, with St Eunan’s, Letterkenny ace Kevin Winston in the other corner.

Between them, at full forward, was John Concannon, their brightest diamond and now a selector under Joyce with Galway.

One of the famous chants from the partisan Maghera supporters that year was the “you’ll never beat Sean Lockhart”, to a similar tune Nottingham Forest fans sang about their speed merchant Des Walker in defence.

“Concannon went for the first ball, threw me a dummy and stuck it in the net,” said Lockhart of a testing afternoon in Pearse Park. The chant soon stopped and Concannon’s 1-4 tally helped Tuam to glory.

“They had a freak group,” Lockhart states. “Big John Haran (who was on the Jarlath’s panel) said to big Adrian (McGuckin) a few years later that there was very little between the two teams, but they were more clinical and got scores at the right time.”

On the bus up the road, with 15 of the panel underage the following year, tears were wiped away and promises were made. They were going to go the whole way in ’95.

After a convincing win over St Colman’s in the final – the only MacRory decider ever held in Clones – it was Lockhart who climbed the steps to hoist the coveted trophy aloft.

SKIPPER…Lockhart captained St Patrick’s Maghera to MacRory Cup glory in 1995

He missed out on the Hogan Cup with differing age grade for the All-Ireland series, with inside forward Fintan Martin, midfielders David O’Neill and Mark Diamond among six players overage.

“Adrian still made us tog out,…you were part of it but you didn’t feel part of it,” Lockhart said of a group he felt succeeded due to a “humble” nature from not all winning trophies on their way up the school.

Like the Hogan Cup winning group he coached with Martin McConnell in 2013, after losing the MacRory final 12 months earlier, it lit a fire. Like hunger, hurt is a potent sauce.

Lockhart came into the school when clubmate Gregory Simpson played on the first Hogan Cup winning team in 1989.

“You looked up to him and you heard of boys like Eunan O’Kane and Ryan Murphy,” Lockhart said.

“I was in first year and Anthony Tohill was in sixth form…he was a giant. When they came in with the cup you are asking yourself if we’ll get to that level.”

Lockhart compares his time in school to touring Australia with Ireland. In both environments, he often felt like pinching himself; such was the level of enjoyment and satisfaction.

“I was watching a show about (Pep) Guardiola the other day and he was saying his group was humble. Our group was the same, there were no egos,” said Lockhart said, comparing it to his MacRory group.

An appendix operation forced him out of the D’Alton campaign and he returned to sit on the bench as St Pius, Magherafelt beat them out the gate in the final.

“You’re sitting thinking we had a bad year group, but six months later we beat them in the Corn na nÓg (group stages) and then again in the semi-final,” Lockhart.

They faced an Abbey team in the final, with Enda McNulty, Aidan O’Rourke, Barry Duffy, John and Tony McEntee in their ranks.

“We were five points up and they scored two goals to win it and my man, Cormac O’Hanlon, scored one of them,” Lockhart said of the last time his age group lost in Ulster Colleges’ football.

Playing for St Patrick’s, Maghera gave him confidence. It brought him to another level. All through the younger age groups in Banagher, it was one of his best friends, Gary Biggs, who was always chosen as Player of the Year.

Lockhart, who concedes how Biggs was just better and more skilful, did pick up the accolade at minor level.

Playing against the top players from across Ulster on blustery Saturday mornings on the fringes of Lough Neagh built character. The driving rain on pitches in Derrylaughan and Brocagh tested your skills under adversity.

“It instilled a confidence that I could compete at this level,” Lockhart insists.

“What our school brought to the table…Big (Paul) Hughes, Adrian (McGuckin) and you had (Liam) Kielt…they were the main characters. Then you had people like Joe McGurk in hurling and Michael McKenna…they all threw their wee bit into the mixture to make you a good player.”

Lockhart is full of praise for Hughes, now a teaching colleague in Maghera, for his 38 years of service in the school and influence on him and the countless players who passed under his watch.

“Adrian always used the mantra of never settling for mediocrity,” said Lockhart of a man who also managed him in UUJ.

“It’s a combination of coaching and your peers,” he said of the players he played with.

“They set high standards. Now, if I take a school team when they are young and get hammered, you do a bit work with them and close the gap.

“Sport is funny that way…it’s about good coaches, good peers and keeping your feet on the ground with a work ethic.

“Nowadays young players have an opinion, but we questioned nothing, you had really good manners.”

Moving on to university, Paul Cunningham, Duffy and John McEntee, rivals at MacRory level with Abbey, played on Lockhart’s UUJ Fresher team that lost the 1996 All-Ireland final to a UCC side that had Alan Quirke in goals and hurling star Joe Deane in attack.

Two years later, Lockhart was the width of a goalpost away from winning a Sigerson Cup in Tralee. When Brian McGuckin’s low rasper bounced out in stoppage time, a star-studded IT Tralee lifted the trophy on home soil. It wasn’t Lockhart’s last meeting with Joyce and Donnellan that summer.

—

When new Derry senior manager Brian Mullins gathered the troops in the autumn of 1995, Sean Marty Lockhart was part of his plans.

There was no gap year and the step from MacRory Cup to inter-county senior was a “massive jump” with the speed of thought the obvious difference.

“I was watching a programme the other night and it was about how Messi thinks two seconds ahead of everybody else…good players think quick,” Lockhart said. The inter-county senior game demanded the same.

After scoring a point on his league debut, coming on as sub in 14-point defeat by Kerry at Ballinascreen in the pre-Christmas portion of the National League, a trip to Ennis for the next game dished out another harsh lesson despite victory.

“I marked Gerry McInerney against Clare in a league game and he skinned me,” Lockhart said of a player imprinted in his memory.

“(Kieran) McKeever and (Henry) Downey came over and said ‘Sean Marty, you’ve made the county, your work starts now’ and that was where it all began.”

Coming into the remnants of the 1993 All-Ireland winning team, Lockhart had a solid base but thinking quicker was now added to his growing list of requirement improvements that already included strength and pace.

By the time they reached the final, Lockhart was not stationed at wing-forward as Derry retained the New Ireland Cup with victory over Donegal for the second year in a row.

When he made his championship debut at home to Armagh later that summer, goalkeeper Johnny Kelly was the only other player on the team not to have helped win Sam three years earlier.

At wing-forward, he was up against John Rafferty in the first half before Kieran McGeeney was switched across. Lockhart registered a point with Anthony Tohill and Joe Brolly scoring 1-9 between them.

Tyrone easily accounted for Derry in the Ulster semi-final, but an All-Ireland u-21 winning team the following season helped bring through a new batch of players.

The Derry players, who mark 25 years since their success tonight (Friday), beat a Meath team (1-12 to 0-5) that included Cormac Sullivan, Mark O’Reilly, Barry O’Callaghan, Paddy Reynolds and Lockhart’s International Rules’ roommate Darren Fay from their Sam Maguire winning crop 12 months earlier.

For the talent in the Derry camp, Lockhart feels the county underachieved in the decade that followed, with the 1998 Ulster title their only championship silver until Chrissy McKaigue raised the Anglo Celt Cup this summer.

Derry went down to Cavan in the 1997 Ulster final before bouncing back the following year with Lockhart now at full-back.

“I was centre half-back and Henry Downey was playing full-back against Mayo in a league game,” Lockhart said of the day Brian Mullins reshaped his defence.

“He swapped me and Henry after 20 or 30 minutes because Henry was more used to centre-half. I hated it, going into full-back and I realised it was a different job in the full-back line and you had to train yourself.”

A run to the National League final, ending in defeat to Offaly, and a stellar championship rounded off by curbing Tony Boyle on Ulster final day had the All-Star selectors marking Lockhart’s card.

“I got (Joe) Brolly to simulate Tony Boyle and he gave me a few ideas,” Lockhart jokes. “He was predictable and I showed him to his other side, so he was winning ball and I was taking it off him.”

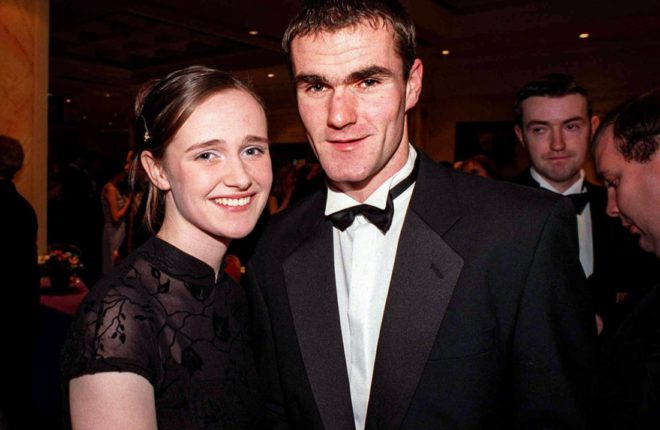

After faring “50-50” with Joyce in their All-Ireland semi-final defeat to Galway, it cemented Lockhart’s All-Star.

STAR…Sean Marty and his wife Miriam at the 1998 All-Star awards ceremony

Ironically, three years later, it was Lockhart’s personally prepared video clips, accompanied by words of advice, that helped Kevin McCloy curb Joyce when Galway beat Derry in the All-Ireland semi-final with Matthew Clancy’s goal.

“McCloy had Joyce tied up, but (Derek) Savage scored four points off me that day and gave me a bit of bother,” Lockhart admits. “Even with that, we controlled the game and that was the one that got away.”

—

Mullaghmeash Park in Feeny was home to droves of children in Lockhart’s childhood. It was wall to wall sport, a hotbed of activity. If it wasn’t football or hurling, it was soccer.

Teams were picked. Some days you won, some days you didn’t. It turned to tennis in the Wimbledon season, with karts scooting around the place on other occasions.

“You just grew up and you made your fun. In that housing estate, you developed that real will to win and the competitiveness,” Lockhart said.

“You lived beside the pitch and that was your life. You didn’t go away on any holidays.”

Lockhart looks at everything as a competition of sorts. He’d make a run and see how high he could reach up a lamppost. The kerbs were used to test his footwork. Left foot up, right foot, then back to his left – tapping like mad.

“Now teams are using ladders in training to work on that,” said Lockhart, who coaches football and hurling teams in St Patrick’s.

They’d head down to the pitch for hours on end and he now passes the stories to his pupils. Before success comes preparation. There are no shortcuts.

Lockhart uses the example of the 2001 Ulster Championship clash with Tyrone and a tackle he made to strip Peter Canavan of the ball in the opening quarter of the Clones clash.

“He went in for goal one time and I knew from watching him that he was going to cut inside and bang, bang (Lockhart says as he claps twice)…I took the ball off him,” he recalls.

From a long way out, Lockhart knew he would be on the Red Hand star. It was time to get the homework done. Trips to Tyrone and Errigal Ciaran games were par for the course, often sitting on the 21 yard line, observing everything. Video footage only tells half the story.

Footage was also trawled before there was such a thing as a dedicated performance analyst and clips fired into a Whatsapp group. It was the good old fashion pause, stop, rewind method.

Lockhart would get people to simulate Canavan’s run and turn. Nothing was left to chance and the 22 hours of individual practice paid off until Tyrone made a change, with Stephen O’Neill pushed into the full-forward line.

O’Neill hit 1-3 in Tyrone’s win. But the Oakleaf summer was only beginning and Derry’s route though the back door – in its first season – took them back to Clones and a second clash with Tyrone in an All-Ireland quarter-final. Lockhart would never be caught cold again.

He prepared for both O’Neill and Canavan. It was back to the harsh experience of getting a tough time, weeks earlier, layered with more time in front of the television.

“You want to see what he does before the ball comes in,” Lockhart explains. “Some players just run for the ball, good players maybe make a dummy run and go.”

“Stephen O’Neill was different. He’d watch the ball in the Tyrone half-back line. His first sprint would drag the defender away from his own goal.

“Then he’d drop back on the blind side, that’s how I got skinned (in the first 2001 Tyrone game) when I was in front of him and he was breaking.

“The second day, I learned and I knew he was going to come so I went with him. I kept him in front of me and when he made the second run I was with him.”

Lockhart held O’Neill to a point from play in a 1-9 to 0-7 win for Derry, with Canavan – who he started on – scoreless over the 70 minutes.

Preparation is a defender’s best friend Lockhart insists. He also offers the example of Trevor Giles not settling until he’d 30 kicks of the ball at training to hone his place kicking. It’s the same for Stephen Cluxton, getting his goalkeeping routine in the locker before regular training had eve began.

“It’s like Mel Gibson (in the film We Were Soldiers) leading the troops to take on the Viet Cong…he has to be in the first helicopter in and in the last one out,” Lockhart adds, comparing it to inter-county football. The extra yards soon accumulate.

DOWN UNDER…Lockhart was capped 16 times for Ireland in the International Rules series

“You realise quickly what you are failing in, if you are not quick enough, if you are not a good tackler or if you have to work on your high catching,”

Lockhart played the game well before the days of sweepers and overly packed defensive systems. There was exposure by as much as 60 yards of space at times in front of two inside forwards.

“You had to be good at attacking the ball, you had to have good recovery, you had to have brilliant footwork and you had to be a brilliant tackler,” Lockhart said of life in the fast lane.

He remembers Anthony Tohill’s suggestion of dropping man into the space being shot down by manager Eamonn Coleman.

“No effing way, he turned to me or McKeever and said “do your f**king job” and it made you the player you are,” Lockhart now states.

“You tried to win the ball. If your man won the ball…we had pride in ourselves that Derry had brilliant defenders.”

It demanded squeaky clean technique and with that came the preparation, something Adrian McGuckin instilled by the bucketful at MacRory level.

“When Ballinderry won the All-Ireland, Adrian got me to watch videos of teams they’d be playing,” Lockhart said.

The jotting down observations began with studies of teams they’d have met in the MacRory Cup. Where did a player turn? It was about checking his favourite side, all the mannerisms and where an opponent fitted in overall.

“For other people, they just want to go out and play the game but it worked for me,” he said.

And it wasn‘t always about a total shut out. Keeping a dangerman to the bare minimum was often a degree of success, with a big far zero beside and opponent’s name was always the optimum.

“I relished people talking about marking the star forwards and telling me ‘it couldn’t be done’, I embraced that challenge,” he said.

Most teams trained on a Tuesday and Thursday before being cocooned in the rest bubble until Sunday. Tuesday was for work, with Thursday left as taper night.

Sean Marty bucked the trend. He upped his game the closer he got to a Sunday. His ritual was an hour at a deserted Banagher pitch on the Saturday before heading for a mouthful of prayers in the chapel in the glen below. And like he was taught from no age, he’d visit the family graves, making sure to stop at that of Fr John McCullagh, Banagher’s Parish Priest before a car accident took him too soon.

That was the routine and Lockhart was ready. Mentally, his 60-minute run out on the grass was a must. With the scenic backdrop of the Sperrins, he’d go through a warm-up before visualising the area a Peter Canavan, Oisin McConville or Joyce would take up and how they would turn, with the help of pause and rewind on the video player.

“You’d have saw this freak on the pitch, buzzing about tackling here and there,” Lockhart says with a smile at what watching a man tackle thin air might look like.

For the warm-up, there’d be shapes mapped out in different coloured cones. Sometimes his wife Miriam would be there calling a colour he’d sprint to before quickly moving to another. It was a step up from the footwork on the kerbs of Mullaghmeash, tuning the reaction speed a Sunday would demand.

“There were other times I would’ve had people coming at me,” he adds. “I had visions of where boys would go, so when it came to a Sunday and the crowd was there you were so confident in your ability to deal with it.”

It was a ritual that worked and made him one of the best defenders of all time. In one of the top counties, he may well have annexed a litany of Celtic Crosses.

—

He eventually called time on his career after Derry exited the Qualifiers at the end of the 2009 season on a day Michael Murphy was causing bother until Lockhart was moved across to curb him.

It was a game Chrissy McKaigue’s late point dragged into extra-time before a Kevin Cassidy goal left Derry chasing a game they’d never catch.

“People say you give things up to get an All-Ireland and I would love an All-Ireland,” Lockhart said. “It comes down to a team and it’s a team game and you need the breaks.”

He is positive of a career that offered more than most. He points to Mark Lynch and Paddy Bradley bowing away without the Ulster medal he holds.

There is a sense of pride in an International Rules career that spanned four trips to Australia and one as a runner.

When he received the call to join the 1998 trials, he was working on a building site during the summer holidays from college. One of the men on the site jokingly bet him £20 he wouldn’t make the panel. And 16 caps later, Lockhart still hasn’t received his winnings.

“Those three weeks you got as a player, you training hard for two weeks and for a week off at the end,” said Lockhart, buzzing with the opportunity he got to see the world and mix with players from all over Ireland.

“To train like a professional, it was just brilliant. One year we stayed in a hotel at Albert Park, which is beside the Melbourne Formula One track.

“We used to go out, train beside a lake and go for a walk around the racecourse and we’d see (Michael) Schumacher in the pit lane.

“There was no work to go to and no books to mark. You’d train in the morning and in the evening in the stadium. It was some taste in life.”

From the day he entered the boxing ring to taste sport for the first time, Sean Marty Lockhart settled for nothing but the best.

All the nuggets of coaching advice and life lessons he received helped him along the way.

Humble he remains and a keen watcher of all things sport. He hasn’t changed one iota.

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere