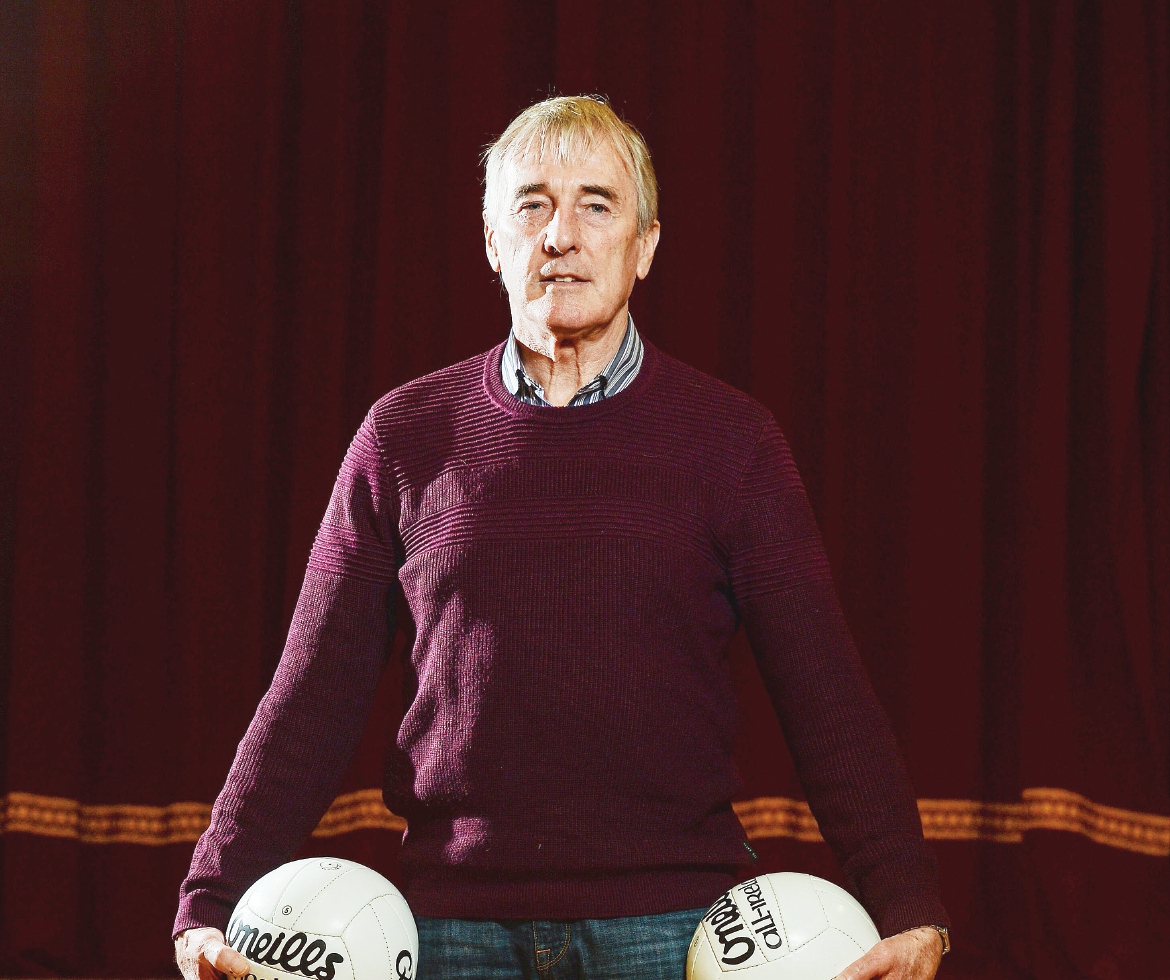

John Joe Kearney won an All-Ireland Minor title both as a player and a manager. He played club football until he was 46 and was Mickey Moran’s right-hand man during Sleacht Néill’s glory years. Michael McMullan went to meet him…

JOHN Joe Kearney turned 77 in June and his memories from a decorated career are as fresh as he looks.

Hanging up his boots at the age of 46, he played competitive football for longer in life than not.

After stepping away from senior football in his late thirties, he moved into the slow lane with Sleacht Néill Thirds where he elongated his career. It was here where he played alongside his son Brendan who was breaking out of underage.

When Mickey Moran steered the Emmet’s to heights of club football, Kearney was his trusted wing man.

Aside from watching games, football is now in the rearview mirror. But it has been good to him and his modesty offers luck as the reason for much of his success.

He produces a box of medals, a reminder of the glory days. Another proud possession is a framed collage of photos he received for his 70th birthday.

The centre photo is a squad photo from Sleacht Néill’s 2014 Ulster winning team he organised himself. Charting history is important.

Then, just when you think you know fully know him, he produces a perfectly sketched picture of John F Kennedy. Aside from football, there is an artistic talent locked away.

If he didn’t reveal it, you’d have no idea he is three years out from being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease.

“When I noticed a bit of a tremble in my left hand, I went private, got it looked about right away,” Kearney begins.

The medication levels are steady. While he is retired from a lifetime of selling timber, there is enough at home to keep him ticking over.

It was never going to keep him down. It was the same when a chainsaw accident could’ve cost him his hand. After sustaining a broken jaw, he donned a hurling helmet to play against Swatragh Thirds, a team that contained a certain Anthony Tohill on his return from Australia.

Below Kearney’s television is a photo of older brother Bernard, who passed away just before the club began their dominance of Ulster. He was chairman at the time. It was a lifetime of devotion to the club.

“We didn’t live in Sleacht Néill,” Kearney begins of his own early interests.

John Joe and Bernard would spend their summers at their Granny’s in Sleacht Néill. The Kellys were the neighbours and they’d kick ball in the back garden.

“I can remember in my adult years going up to look at this wee football pitch in their back garden,” Kearney recalls of their mini Croke Park.

“It wasn’t the size of a good living room, you just played away and the sweat running off you.”

It developed into a ritual of cycling up to play alongside the Kellys before joining the Sleacht Néill underage set-up that, at that time, wouldn’t have crept any lower than the u-16 grade.

Emmett Park today is an impressive beacon of progress by those with the foresight to plan for tomorrow.

Back in the day there was a sum total of one leather football and it was under Joe McEldowney’s watch.

“You went down to his house and hopefully he’d be there,” Kearney said of those days wanting a kickaround. “Secondly, if he was there, he conceded he’d give you the ball for an hour.”

In his time looking after the Sleacht Néill seniors, Kearney prided himself on not leaving training or a game until every ball was accounted for. Money didn’t grow on the trees he’d often be fishing around for a coveted piece of leather.

It’s in contrast to the famous story of Swatragh outplaying Sleacht Néill in a parish derby of yesteryear.

“With about 10 minutes to go, Swatragh were winning the match and the ball was kicked over the bar and down over the road, down into a wee field on the other side,” Kearney explains.

When the ball came back, Pat ‘Ned’ Kelly relayed the message of a burst ball. It was the days of one ball. Without it, the game was over.

“He said ‘she was fizzling like a pot of pratties’ and he allowed they weren’t going to beat Swatragh, so the match wasn’t finished.”

It’s a yarn that never grows old.

***

When John Joe Kearney went to St Columb’s, Derry as a boarder in 1958, football began to get serious.

In the absence of inter-school games, Fr Ignatius McQuillan took an interest in football in the school.

Teams were picked from within St Columb’s for weekend games up at the nearby Termonbacca.

“He then entered us in the Rannafast Cup and that was my first taste of inter-college football, I played wing half-back,” said Kearney, who had left the school a year before a 1965 MacRory and Cup double. There was another obstacle in the form of a cartilage injury that sidelined him for a year.

When the letter came for an operation in the autumn of 1964, he decided against reporting to Altnagelvin for surgery.

“I heard stories that it was done with a knife and it wasn’t very successful,” Kearney weighed up. A 50 per cent success rate and the risk of a “bad knee” didn’t enthuse him.

While Derry minors were making their way to the Ulster final, Kearney was still out of football until a minor game in the colours of Granaghan – a mix of Swatragh and Sleacht Néill – against Kilrea.

Derry minor manager Fr Shields liked what he saw and invited Kearney to training.

“I just started working on Chemstrand in Coleraine at the time and I was working night shifts,” Kearney outlines.

He left instructions with his mother not to wake him. Parachuting in ahead of a final didn’t sit well. Shields had other ideas, arriving to get Kearney out of bed, taking him to training in Ballinascreen. The rest is history.

“Three weeks later, for the Ulster final, I was in the full-forward line of the Derry minor team,” he said.

It was about managing his knee. Without the operation, a bandage was used for support for the entirety of his playing days.

Derry minors went on to win the All-Ireland Minor title and the All-Ireland U-21 three years later.

“That’s how lucky I was to win two All-Ireland medals,” he said modestly.

READY TO GO…John Joe Kearney (second right) pictured with Seamus McCloskey, Eamonn Coleman, Mickey Niblock and coach Sean O’Connell before the 1965 All-Ireland minor final

There was some senior county football but working shifts and training didn’t fully align.

After winning an Ulster Junior title, Derry travelled to Tralee to face Kerry in the All-Ireland semi-final.

Midway through the first half, Derry matched the Kingdom until Kearney’s rasper broke the wooden crossbar.

“The game was suspended for another 20 minutes until we got the crossbar fixed,” Kearney utters with a smile. “We played none after, that always sticks out in my mind.”

At that time, while working in Coleraine, Kearney was tapped up to try his hand at rugby. It was the time of the ban on GAA players’ involvement in other sports. It was time for an alias and GAA player John Joe Kearney now doubled up as Jonathan King the rugby full-back.

“They were a good bunch of lads to play with and it kept your fitness level up,” Kearney said, pointing out how the football and rugby seasons didn’t cross.

Rugby kept the body ticking over enough to make any form of football pre-season bearable.

“Keeping the two going, I was always very fit,” said Kearney.

It took time for the rules to embed. The shape of the ball was different and throwing it backwards didn’t come naturally. Kearney had to learn on the job.

“I remember the first game,” he began. “We were in Belfast and this ball came down. I caught a hold of it and that was the first time I’d caught a rugby ball.

“I booted it up the field. I was standing looking, thinking ‘Christ, that’s a great kick’ but I didn’t realise that you had to get up ahead of the play to bring all the other boys onside.”

It was a learning curve, but an enjoyable one. His placing kicking on the Gaelic Football fields meant he’d kick all the penalties and conversions to top the charts.

In terms of physicality, Kearney didn’t see any “heavy hitting” comparison to the game now. He does remember the one day he was taken out on the rugby field.

On seeing a first challenge coming, Kearney thought the coast was clear.

“Another boy, and I could see him coming by the tail of my eye, he hit me in the middle of the back and put the both of us into touch,” he said.

There was a twinge in the back. That was Saturday with a Sleacht Néill game to follow on the Sunday.

“I was in for the throw-in at the start of the game, and I went up for the ball, and some of the opposition players came in underneath me, and I went down, flat on my back,” Kearney said of his football game ending early.

“That’s the only knock I ever got, playing rugby. And I got to see my career without too many injuries.”

***

Sleacht Néill’s first county final appearance came in the 1969 when they came up short against market leaders Bellaghy.

It was as close as they came until their 2004 breakthrough after an Ulster winning minor group came to fruition to add to an established core who were dancing with the top teams without any real success.

The 1969 group were a solid group of around 20 players. Unless injury came into play, the same 15 fielded most days and it was an enjoyable era when carnival football added to the overall package.

When the players called time on their playing careers, they ploughed energy into coaching, club administration and lending any welcome hand to write the next chapter.

Kearney was coaching the club’s underage teams when Ballerin man Mickey Bradley sounded him out about taking over as Derry minor manager in 1988.

“To be honest, I didn’t think I’d be capable of doing it,” Kearney said, looking back at how was coerced into the role.

Trials began and players were whittled down before a first round exit at the hands of then All-Ireland champions Down.

When the 1989 campaign began, St Patrick’s, Maghera were on their way to lifting a first Hogan Cup.

The talent was there but minor football is always a gamble of sorts in the first round, integrating college players who hadn’t been on board for the league.

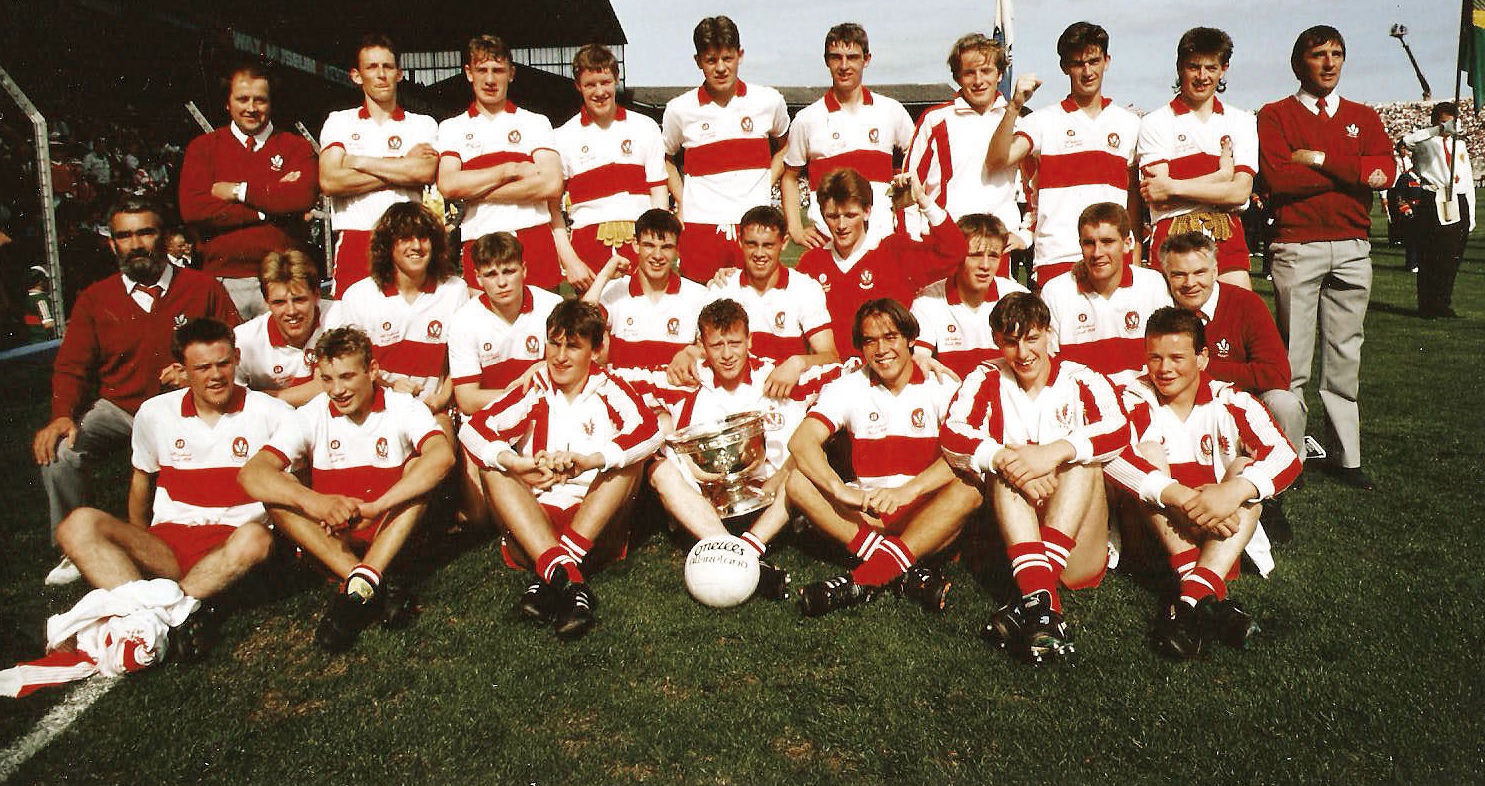

CROKER OAKERS…John Joe Kearney (back right) after Derry’s 1989 All-Ireland minor final win over Offaly

Fermanagh were rated highly at the time but two goals helped Derry emerge winners ahead of a semi-final with Cavan that turned the season.

In the build-up, Kearney’s selector and fellow Sleacht Néill man Willie Hampson suggested taking in Dungiven’s Senior Championship game to run their eyes over minor players Eunan O’Kane and Ryan Murphy.

“They were both playing in the right wing. Ryan Murphy was playing right half-forward and Eunan O’Kane was playing top of the right,” recalls Kearney, also remembering how Brian McGilligan supplied them from his full-forward role.

“They destroyed Claudy. On the way home, Willie said to me that if we’re in difficulty someday, we’re going to change the team around and put the two boys in that wing together.”

The change was needed sooner rather than later. Cavan were eight points ahead going into the final quarter in Clones. It was time to bring O’Kane on from the bench.

“It looked like we were dead and buried,” said Kearney.

The deadly duo changed everything with a combined 3-3. Murphy bagged the first goal with O’Kane hitting the net before Cavan rallied to get their noses back in front.

Kearney can still see O’Kane going through for his second goal. A point would’ve earned a replay and Derry could regroup.

“Eunan put it into the net, put it in the right-hand corner like a rocket,” he said.

Derry breezed past Armagh, Roscommon and Offaly to land the All-Ireland, writing Kearney into history as a minor winning player and manager.

The volume of games, between club and school, eventually told the tale. Maghera retained their MacRory and Hogan Cups but the players were running on empty before the 1990 All-Ireland Minor semi-final with Meath.

At u-21 level Kearney steered Derry to Ulster glory in 1993 before falling to eventual All-Ireland champions Meath after a semi-final replay.

Kearney used the word luck for his success. Had Fr Shields not pulled him out of bed to get him to minor training, his medal collection would’ve been a paltry one.

Without O’Kane’s goals, Derry’s 1989 adventure doesn’t even get as far as Clones on Ulster final day when they saw off an Armagh team that included Neil Lennon.

“Funnily enough, I had been reminiscing and watching it (Ulster final) about a month before I met him in Vilamoura,” Kearney said.

Lennon had just been appointed for his first stint as Celtic manager. Spotting him coming towards him in the marina, Kearney introduced himself before offering best wishes for the Parkhead hotseat.

Chat turned to the 1989 Ulster Minor final. Lennon remembered it well. Conversation was plentiful. Derry’s quality left an impression.

***

When Mickey Moran was linked to the Sleacht Néill job ahead of the 2013 season, he touched base with Kearney about coming on board.

Farming and selling timber wouldn’t leave enough time and he declined. Fast-forward 12 months, Moran is appointed and Kearney accepted.

While not that well known to each other, it was the perfect match.

Without Moran’s influence, Kearney questions if championship success would have arrived.

There was a talent pool to work with but there is also the elephant in the room of the 2014 final with Ballinderry and whether Gerald Bradley’s flicked goal actually crossed the line.

At the time, chairman Sean McGuigan’s word of choice was ‘unbelievable’ at the plethora of championship winning homecomings. Kearney agrees.

“Some of the matches were on a knife edge,” he said of the dramatic moments along the way.

Conan Cassidy’s run and Cormac O’Doherty’s pass for Christopher Bradley’s winning score to beat Omagh in the 2014 Ulster final.

He can still see the ball hanging in the air before dissecting the posts to send the club into dreamland.

Kearney also remembers their rollercoaster against Kilcar in the 2017 semi-final when Ryan McHugh couldn’t shake off Karl McKaigue.

The image of McHugh’s outstretched arms after another McKaigue disposal comes flooding back, as if to concede the individual battle.

While the management formula was in tandem, Kearney is quick to point to the players’ commitment.

WING MEN…John Joe Kearney pictured with Mickey Moran as they suss out Sleacht Néill’s next step

Socialising was put to one side for the greater good and kept for celebrating victories or the rare window of downtime.

There were no troublemakers. Anyone not making the cut, put their shoulder to the wheel.

Moran instilled discipline. Getting balls moved forward wasn’t accepted and the appointment of Francis McEldowney as captain was a masterstroke. He was forced to airbrush any past frustrations.

Training was different, fresh and engaging, with no shortage of games to sharpen the focus.

“We always had at least three dozen to train, which meant you had two teams to play against the other – and those matches were hell for leather,” Kearney.

It brought the best out in everyone. There was needle but the right sort of needle that primed their path to four Derry and three Ulster titles.

The other rollercoaster days were the All-Ireland semi-finals. A comeback from two penalties to sink Austin Stacks in 2015 while they tamed St Vincent’s two years later. In the other, Nemo Rangers reeled them in from a position of control.

For Kearney, the four years was a memorable imprint but not winning an All-Ireland still lingers.

He wakes up and thinks of Padraig Cassidy’s sending off in the 2017 final defeat to Dr Crokes and how referee Maurice Deegan took advice from his linesman.

“They (Dr Crokes) took him (Cassidy) out deliberately,” Kearney said.

“That still sticks in my craw because we were two points down, we played with 14 men and we lost by two points.

“I’m still of the opinion that if Paudie Cassidy had stayed on the pitch we’d have won an All-Ireland. In some respects, I think we were done out of it.”

Looking back on their golden years, Kearney immediately links in the success of the hurling and camogie teams.

“The name Sleacht Néill, no matter where you mentioned it in Ireland, that meant something to people,” he proudly points out.

The club remains in rude health and respected. The rivalry with neighbours Glen and Swatragh still exists. And always will.

“There’s no harm in going out and doing your best to beat the opposition,” Kearney offers, “but when the match is over, shake hands and get on with it. That’s the way it should be, in my book.”

A career that started with cycling a 12-mile return trip to play for Sleacht Néill took Kearney to Croke Park as a player and manager before taking him back to a memorable final footballing chapter.

“From 2014 to 2017, they were four great years,” he concluded. “The only thing, the body was 50 years too old.”

• For the full interview with John Joe Kearney, check out this week’s edition of Gaelic Lives. Link below…

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere