Ross Carr reflects on a special career in the famous red and black of Down. Shaun Casey writes…

SOMETIMES fate just can’t be avoided. It’s written in the stars for some people. Before Ross Carr ever set eyes on a football, he was destined for greatness. Looking back on his career, he didn’t really have a choice.

From an early age, he had a close connection with Down GAA that most people from the Mourne County can only dream of. Everywhere he looked, he was rubbing shoulders with some of the greats.

Kevin Mussen, Down’s All-Ireland winning captain from 1960, was not only a Clonduff clubmate of Carr’s but also his local primary school principal. Patsy O’Hagan, a two-time All-Ireland winner, was his next-door neighbour.

Even inside the Carr household, there was no way to avoid it. His mum taught in a school alongside the great Sean O’Neill’s mum. Carr’s uncle Barney had managed the Down team to their first All-Ireland triumph in 1960.

His other uncle Gerry, both his father’s brothers, captained Down to an All-Ireland Junior title in 1946, while his father Aidan was a member of that team. His cousin Seamus won an All-Ireland Minor title in 1977. Carr had no choice but to pursue the Down jersey.

“I suppose I wanted to make sure that I was contributing to the DNA. I needed to hold my head up at family functions,” laughed the two-time All-Ireland winner.

“When I was growing up, it was a totally different time, but it was football mad. My mother’s family was steeped in the Clonduff club, and my father’s family were from Warrenpoint. They were all involved and had a long history with Warrenpoint and with Down.

“A lot of my early years, I was surrounded by huge GAA influences especially at home but outside of the house as well, so it was no big surprise that I went on to have a huge interest in Gaelic games.”

Seeing his heroes inspired his footballing journey. “From six or seven I had huge influences around me steering me down the GAA path. I had an incredible childhood; we used to go to all the Down games and the Railway Cup was a huge thing at the time.

“The Down team that won the All-Ireland in 1968, a lot of those players were playing for their clubs in the ‘70s and even into the mid-80s and I was going to club games just to get seeing those superstars and it was fantastic.

“Once I was playing more, I was coming under the notices of representative teams. I got on the county u-16 team in 1980 which was managed by Pete (McGrath), and I was on the minor panel for a couple of years and then the u-21 panel.

“Without having a plan, when you’re in those environments, you’re probably already doing the right things. You’re training hard, you’re practicing, all the wee cliches things. There was always a deep, deep desire to represent Down.”

The ‘60s saw Down carry Sam across the border on three occasions. The county suffered a dry spell on the national stage after that, but there was enough bubbling beneath the surface to suggest they could rise again.

Carr was called into the senior squad in 1986 and Down had only won three Ulster titles since their last All-Ireland success in ’68. But then again, it’s always darkest before the dawn and Carr knew they weren’t far off competing for the big prizes.

“While there was a massive gap in senior success, Down had won a minor All-Ireland in 1975, an Ulster Championship in 1978 and an u-21 All-Ireland in 1979,” added the 1991 All-Star attacker.

“We were getting to Clones at that time, an All-Ireland semi-final. There was no national success at senior level but there was enough to keep the interest going.

“Down had won a National League in 1983 and while that’s eight years beforehand, there were a number of those players still in the panel in ’91. We were beaten in an Ulster final in 1986, and we were beaten narrowly in Ulster semi-finals in ’88 and ’89.

“1990 was probably the worst of the years for Down and there was a lot of soul searching that had to be done. I think maybe for the first time it probably dawned on me that honest conversations had to take place.”

That 1990 season was the turning point for Carr. He needed knee surgery and was dropped from the Down team for the first time in his career. He stepped back from the inter-county scene but even at club level, he wasn’t reaching the performance levels required.

Clonduff appointed a new manager, a relatively unknown name in Frank Dawson. He helped give Carr a new lease of life. Once he found form again, a conversation with McGrath saw him rejoin the Down squad in April of ’91. How different things could have been.

“It’s hard to imagine at that time what was going to unfold,” Carr reflected. “We had a number of young players that came through and I honestly believe that we had three of the best forwards in Ireland in Greg (Blayney), Mickey (Linden) and James (McCartan).

“It was highly unlikely that any other team was going to have three defenders to mark them, so I always felt like we had a chance. It was a case of getting everything right because there was a serious number of strong personalities in that group.

“Everyone has to put in a shift and for five or six months that’s what happened, and we ended up winning the All-Ireland. It was an incredible summer.”

Carr’s influence shouldn’t be understated. By the time the season ended, the Clonduff sharpshooter had racked up 0-30 in six games, with his accuracy from frees making him the second highest scorer in Ireland. Down not only won Sam, but Carr claimed an All-Star.

“From an early age I was always hitting frees. I was probably the second-best free taker that Down had at that particular time, Gary Mason was the best. He was the best striker of a dead ball that I have ever seen.

“I would have practiced daily. I got a job as a trainee accountant with John McMahon, his offices were up in Camlough, and it was straight across from St Paul’s secondary school so I would have used lunchtimes to practice on their pitch.

“Because I was so close to Newry, I would have arrived at training maybe an hour before and practiced then. The football pitch at home was only down the road from me so I was able to get a bag of balls and head down and practice.

“If you look at some of the great kickers now, they go through routines, and I had a bit of a routine, but I kicked until I was confident enough to leave it. I kicked for hours until I got it right. Sometimes the lack of science and naivety was as good as anything else.”

Carr and his teammates had followed in the footsteps of their heroes from the ‘60s and giving something back to them and all the people that had sacrificed so much for Down football over the years was what made ’91 so special.

“That summer was very special for a lot of reasons,” Carr continued. “That group from the 1960s were brilliant for us. Even though it was new for our team to go into Croke Park in an All-Ireland final, the 1960 team had reached out.

“Some of them came to training, some would have sent you messages, and some would have spoken to us about what it would be like and the atmosphere. Kevin (Mussen) was incredible, he was only at the end of the phone.

“Patsy O’Hagan was constantly in contact, Colm McAlarney, who was my hero, these people were always there. Leo Murphy, Peter Rooney, they were just brilliant, so we didn’t actually have a lot of nerves going into it.

“After we won it, it was brilliant for us, but it was so enjoyable seeing what it meant to so many others. It was nearly payback for a whole lot of people who had made sacrifices for all of us during our careers.

“It was brilliant to see what it meant to the families of the players and then when we went back into our own clubs, to this day people from my own parish would still talk about what it meant.”

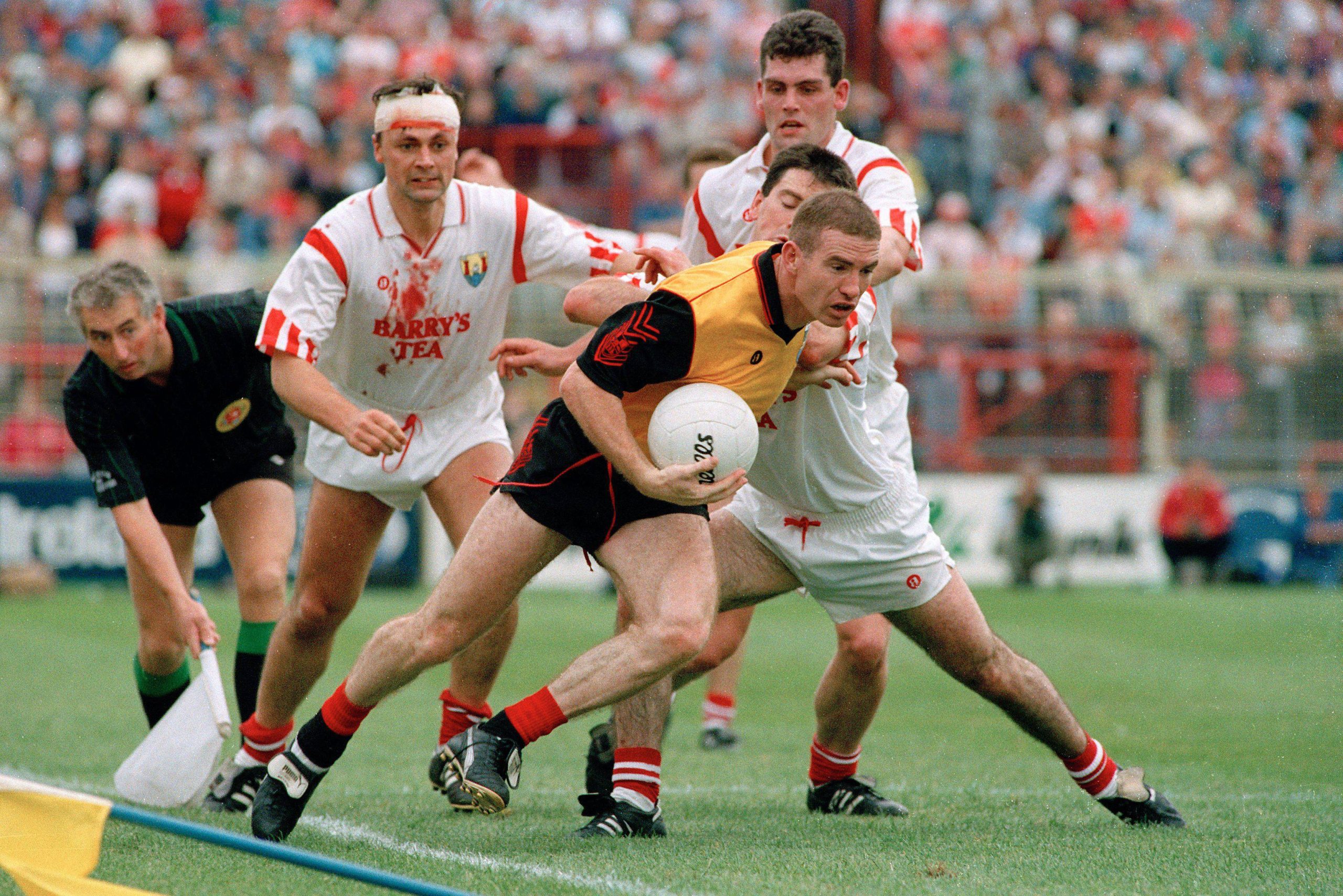

Down failed to reach those same heights in ’92 and ’93. Derry proved too strong on both occasions, winning the All-Ireland title in ’93. Come 1994, the two sides clashed at Celtic Park in a game for the ages.

“We had to go to Derry in ’94 and they were the All-Ireland champions. Given it was a knockout game, if we didn’t get over that then there were no second chances, so we probably had to peak for our first-round championship game.

“By all accounts, it was one of the best games ever, but I was shite. I didn’t have a great game that day, but I got better as the year went on and once we got to September, it was really hard to stay at the top of your game for five months.

“We had done a serious amount of training from January, we put in an incredible shift. That fitness carried us on to the Ulster final and I would say the Ulster final against Tyrone was, over that period, probably our best performance.

“Had we had another bad year in 1994, it’s quite possible that a lot of careers would have been over. When we won that, while there was no difference in the enjoyment compared to ’91, that gave me more personal satisfaction.

“94 was more of a personal justification that if everything’s level and it’s down to hard work and ability and people stay fit, we were every bit as good as anybody else and if we were given the chance, we could show that.”

The Ulster semi-final was marked with sadness, however. Their meeting with Monaghan at the Athletic Grounds in Armagh were overshadowed by the events of the night before at Loughinisland.

“It was a very emotive journey that year because the Loughinisland massacre happened the day before we played Monaghan, it happened that night and for anybody in Down around that time, that will stay with them forever,” recalled Carr.

“Some of the people that were murdered, we knew family members, some of them played with Loughinisland and we would have played against them. We were training with Gary (Mason) from Loughinisland and he knew every one of those people that was murdered.

“It was probably the first time that we realised there were some things far more important than football. Looking back, I think it was the right thing to play the game and having spoken to some of the families since, that summer helped deflect from some of the horror.

“That day in Armagh, there was hardly a clap. My memory of it is that it could have been played on top of a mountain. There was no atmosphere at it, there was no noise, it was a strange event.”

Down came through those difficult tests and finished on the steps of the Hogan Stand for the second time in four years. Carr and many of his teammates collected a second Celtic Cross and gave the Down people memories that will last a lifetime.

But all good things come to an end and while Carr kept striving in the red and black, time waits on no man. He eventually called time on his county career at 39 years of age having given everything to the Down cause that he could.

Remarkably, Carr’s career was bookmarked by what he achieved at club level.

Called up to the Clonduff squad at just 16 years old, the team won the league and championship double in 1980. Twenty years later, they repeated the feat.

“I was coming 16 and I was called into that panel. There were great men on that team that had played for Clonduff, and they were incredible fellas to go into a changing room with and to this day they would be held in series high regard within the club.

“I was 39 when I stopped with Down but in Clonduff, we had a very special group of young lads that had dominated the underage scene from they were young teenagers, they had won everything, and they were starting to come into the senior team.

“I thought I better hold on and try to stay as fit as I could because when those boys came through, they were going to win a championship. Frank Dawson came back in 2000 and brought another wave of enthusiasm about the place.”

Carr played for another season, lining out in the club colours alongside his son Aidan for a year. After that he stepped into various management roles at both club and county level and his still helping out with the Clonduff committee.

“I was incredibly fortunate to have a playing career that allowed me to play for as long with so few injuries and while the success was periodic, when it happened it was incredible, so I was able to bow out having had a right go at it.”

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere