SMALL and seemingly insignificant glimmers of light were beginning to shine on Ulster football as we waved goodbye to the ‘80s and heralded the dawn of the 1990s.

Hindsight is, of course, a wonderful thing. It’s easy to reflect now on the many different things that came together to catapult Ulster football from the doldrums to Sam Maguire dominance.

The revolution grew from humble beginnings. The emphasis on coaching at St Patrick’s Maghera, St Colman’s in Newry and Abbey CBS in Newry, the influence of visionaries like Val Kane, Peter McGrath, Adrian McGuckian, Eamonn Coleman, Art McRory, Jim McKeever and others.

Success bred success on the field. MacRory and Hogan Cup triumphs, Sigerson Cup glory and All-Ireland Minor titles raised the bar, and increased the confidence of new and ambitious players.

We can look back now and see a link. But in 1990 things weren’t really stirring. Instead, the same old story of Ulster champions heading to Croke Park and losing All-Ireland semi-finals emphatically looked inevitable.

Down’s situation was even more dismal. Past glories weighed heavily, so much so that even an Anglo Celt Cup looked beyond them.

Look more closely, though, and perhaps the signs were there. But it took that vital element of good fortune to turn the tide on past failings and open the door to a glorious decade.

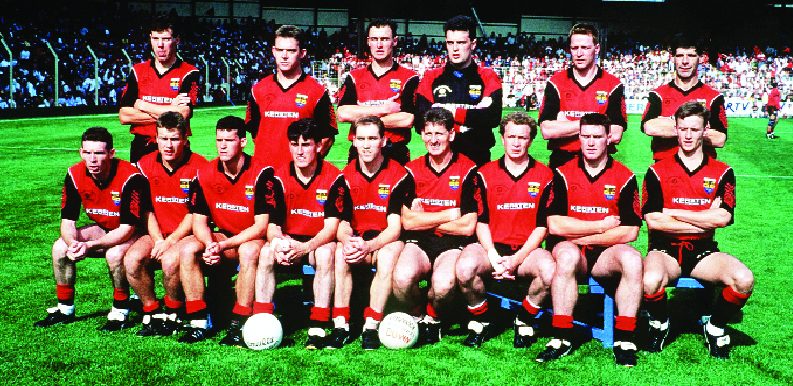

Perhaps, it had to be Down. Their swagger, confidence and attacking brand of football had captured the imagination in the 1960s. Now, 23 years on from their last All-Ireland, a new generation of players were ready, willing and able to forge their own history. They, in turn, pave the way for others to follow.

DJ Kane remembers that time vividly. Ross Carr’s equalising point against Derry in Newry, the momentum of their Ulster final victory over Donegal and then the confidence held when entering the All-Ireland semi-final against Kerry.

“At the start of 1991 nobody on the Down team would have encouraged anyone to bet on us to win the All-Ireland,” said Kane.

“For one, I certainly didn’t envisage myself being at Croke Park in September. Our team was progressing and getting better and we had been doing well in the National League for a few years, reaching the quarter-final, semi-final and then the final in 1990.

“Meath were the top team at the time and we met them on each occasion. In those days if you were able to nearly go toe-to-toe with Meath then you were on the right road and making progress.

“Down always challenged them and there was never much between us. We knew we were getting better and getting closer. Meath could play football, but they could also be physical. They were probably the best team to learn from at that time.

“The Down players did learn a lot from them. In 1991, we suddenly realised that we had a chance of progressing and all those lessons got us over the line.

“But you need the breaks and the two games against Derry in the 1991 championship were very tough and close. For me, winning the Ulster Championship that year gave us a great boost.

“We beat Donegal, who were Ulster champions and had a lot of decent players. Once that happened we knew we had a good chance and were beginning to deliver. Once we beat them in the Ulster final, everyone knew it was going to take a good team to beat us.”

History beckoned and Kerry in the All-Ireland semi-final held few fears for this new-look Down team. Peter Withnell’s bustling full-forward play was a highlight.

The Kingdom of Mourne had never lost to the Kingdom of Kerry in the championship. Now, DJ Kane and company were keen to add the year 1991 to 1960, 1961 and 1968.

“We didn’t have any particular fear of Kerry in the All-Ireland semi-final, apart from the fact that it was them.

“Obviously they had an unmatched tradition unmatched and still had Jack O’Shea, Tom and Pat Spillane, Eoin ‘the Bomber’ and Seanie Walsh. But, in fairness, this wasn’t Kerry in their prime.

“Down had a good record against them. Yes there were nerves, but it didn’t faze us that much. Nobody panicked about going to Croke Park or playing against Kerry.”

Suddenly, from being relative unknowns and no-hopers at the start of 1991, Down found themselves in the All-Ireland final. Standing against them were familiar opponents from Meath.

Of course, this was no ordinary team from the Royal county. In the previous five years they had blazed a trail with a combination of teak-tough play, with the silky skills of an attacking unit that contained Bernard Flynn, Brian Stafford and Colm O’Rourke. Put simply, under the management Sean Boylan, this Meath team could give and take in equal measure.

That All-Ireland final remains a classic, probably in the top 10 Sam Maguire deciders of the modern era.

The 1-16 to 1-14 final scoreline says it all. Behind that bare statistic, lies a story of what Kane describes as one of the toughest matches in which he was ever involved.

“All of us knew that Meath were going to be down the road waiting, albeit it took them a while to get there,” says the former teacher.

“Meath were a completely different prospect. At the time they were probably the best team in Ireland and could play football any way you wanted.

“Down had been playing against them for the previous four or five years. Many years later Sean Boylan told me that at that time when they wanted a really good challenge game to get ready they always came and played us because the games between us had been really competitive.

“Although we knew we were entering the Lion’s Den, so to speak, it wasn’t the case that we entered those matches without hope.

“The first 15 or 20 minutes of that match were hectic. The intensity of the game meant that you had very little or no time on the ball. If you held onto possession you were hit and probably by more than one player.

“It was a case of moving the ball quickly. The problem was that this didn’t make for great passing because you literally didn’t have time. There were tackles flying in everywhere and from both teams. We were flying in everywhere we could because that was what football was like at that time. Sending offs in the first 15 or 20 minutes were rare at that time.

“It was hectic, nip and tuck, but the important thing was that Down were matching them. Then we just hit a purple patch where everything was brilliant – each pass worked, each move worked and every score went over the bar. There was complete perfection for 15 or 20 minutes and we went into double figures. That was a brilliant period of play.”

Games involving Ulster teams in this period generally followed a familiar trend. Initial hope usually evaporated in the last quarter when the favourites from Leinster or Munster would come back to win reasonably comfortably.

Monaghan in the 1985 All-Ireland semi-final, Tyrone in the 1986 All-Ireland final and Donegal in the 1990 All-Ireland semi-final had all seen victory snatched just when it seemed that famous wins were within grasp.

Now, as that 1991 All-Ireland final entered its closing stages, the big question centred on whether Down could hold on. The answer was in the positive, although only after a certain Colm O’Rourke had spearheaded a brilliant Meath revival.

“We are the team that beat the team they said couldn’t be beaten,” proclaimed Peter McGrath on the following Monday night in Newry. For Kane, the sheer joy was also clear once that final whistle unleashed an outpouring of joy.

For this was about more than a mere football match. This was a province, ravaged by the sectarian killings of the previous 25 years, suddenly finding its voice. Yes, it was Down’s All-Ireland, but the victory was shared by all regardless of their county of origin.

“Meath had their period of dominance where they came back on us and threw everything at us. Luckily we were able to hold on and pick up a few points even during that period when they were on top. Those scores kept us ticking over and eventually proved to be enough.

“For me and I’m sure for the rest, winning an All-Ireland was something you had dreamed about since you were a kid in primary school. Our teachers told us to write a story and we wrote one about football and lifting the Sam Maguire.

“It was extra special for me because my brother Val had won in 1968. Now, here was another member of the family winning an All-Ireland medal. Our cousins had won as well, and it was a big thing to have a new generation reaching that level.”

The celebrations went on until dawn on the Monday after the final. They went on for months afterwards, too. DJ says there was an “inevitable hangover” from winning the Sam Maguire, what with the never-ending round of presentations.

While Down’s edge slipped, their success inspired others. The rich dividend of so many frustrating years filled by near misses, what ifs and squandered opportunities was finally yielded.

Donegal came in 1992 by winning their first All-Ireland, Derry trounced Down on their way repeating the feat under Eamonn Coleman in 1993. Ulster was on a roll by the time DJ was appointed captain in the autumn of that year.

“We thought we were on the money again come 1992. But the reality was that the hunger had been lost,” he candidly admits.

“In 1993, we played terribly against Derry in Newry. There were a few injuries going in against them and maybe those players shouldn’t have played. We thought we were back on the right road in 1993, but we were terrible against them, absolutely pathetic.”

No-one knew for sure that Down would be capable of coming back. It was against this backdrop that themselves and Derry played out a Celtic Park classic still rated as one of the best ever games of Gaelic football.

“The Derry game is rated as one of the greatest matches ever. But during it we didn’t think about that. What I do remember is during the first half thinking about how intense the match was, you had no time on the ball and had to move it very quickly when you did have possession.

“You sort of knew that the scores were really coming very regularly. I remember thinking that the game was flying, but you’re so much caught up in the moment that you can’t really think whether it looks good or not.

“It was a case of who stumbled first. The stats man now would be telling us we were terrible, but at the time the game was first class. We were so relieved afterwards because we knew going into that tie how it could have gone either way.”

Victory over Derry set up a semi-final tie against Monaghan. But it was overshadowed by the events at Loughinisland when loyalist gunmen shot dead six people who had gathered to watch Ireland against Italy in that year’s World Cup.

The match went ahead just hours later, although just how anyone was able to focus on the on-field events defies belief even now 25 years later.

“The win over Derry gave us the opportunity to maybe push on and look down the road a little further. Monaghan weren’t at the level they had been and it was a difficult game because of the shootings in Loughinisland the night before.

“We weren’t sure whether Gary Mason would play or not, but he did. There was understandably a very subdued mood, among the team on the bus and at the ground. Gary made his own decision to play with no pressure and even afterwards there was no great euphoria at the result.”

Tyrone were defeated in the Ulster final and Down confidently disposed of Cork in the All-Ireland semi-final.

For DJ, though, the captaincy had brought with it extra pressures. Not least among them was the desire to avoid becoming the first and only Down captain to have lost an All-Ireland decider.

“I suppose the Ulster semi-final and final that year were two games that we were expected to win and did. In the decider against Tyrone, we were fairly comfortable, even though they had got a goal that brought them into it a wee bit.

“One thing that should be remembered about that Down team was the fact that all the players were fairly big and played in central positions for their clubs.

“I think that gave us an advantage in the Ulster final and All-Ireland semi-final. For most of the game against Cork in Croke Park, we managed to stay ahead by two, three or four points. We always seemed to be ahead, and, while they did come back at us, we always seemed comfortable enough in finishing them off at the end.

“At that time the Dubs hadn’t won the All-Ireland and every year they were being made favourites. Maybe that did add a bit of pressure for them. Charlie (Redmond) had a bit of a history with penalties.

“There was extra pressure on me because of the other things that you were involved in. I had to consider the other players and make sure things were being done right.

“To be honest, the team itself had any number of leaders. It wasn’t a case where you were on your own. There were loads of players who had been there and done that – other leaders like Ross Carr, Greg Blaney, big Eamon Burns and even James McCartan, who even though he was much younger was still a central figure.

“They were an easy enough crowd to lead because there were plenty of them delivering on the pitch as well.”

A James McCartan goal in the first half provided them with the confidence required to press ahead. Then, there was Mickey Linden. In a season that saw him win the Footballer of the Year accolade, his performance on that famous day was a high point.

“A lot of the build-up to that final was familiar for us having experienced it previously in 1991. We had won the previous four All-Irelands and I didn’t want to be the captain of the only team to have lost in the final.

“There was always a lot of expectation surrounding Dublin at that time. In that final, I remember the rain started and a lot of the players changed their boots just before the match. It was a dark and damp day, the conditions became slippy and again we probably grabbed the initiative by getting a lot of scores.

“But for whatever reason, our level dropped midway through the second half and the Dubs got a penalty. The save from Neil Collins probably won the game for us. If they had scored a goal at that stage, we wouldn’t have had time to come back. So the save was crucial in terms of boosting us and knocking the heart from them.”

For Kane came the honour of collecting the Sam Maguire on the steps of the Hogan Stand. It marked the culmination of a glittering career and a moment that he’s understandably never forgetten.

But, that was as good as it got for the Mourne men. From then on, their hopes of adding a third All-Ireland never materialised as a combination of injuries, retirements and narrow losses took their toll.

Still, the memories of 1991 and 1994 abide.

“The dream had been to win an All-Ireland. It was brilliant to win two and to be captain was all your birthdays rolled into one,” he admits.

“As you get older you probably realise how important it is – only one person does it every year in the whole of Ireland. At the time you’re caught up in the joy and excitement.

“It was a lot of pressure lifted from me when they actually won – the record was still intact.

“Down lost an Ulster final in 1996 and then I retired in 1997. I fractured my cheekbone in 1996 and didn’t finish the game. Donegal beat us in the first round. We didn’t get the rub of the green but I firmly believe that we were probably good enough to win another title at that time before we got too old.

“I think we would have been good enough in 1996. We were still a good team, the boys were still young enough there was still mileage in the legs and the experience would have helped us. But we fell short in the Ulster final obviously.”

Now, 25 years on, the wait for that sixth continues. The vivid images of DJ Kane and his teammates blazing a trail will adorn the big screen at Croke Park on September 1.

Needless to say, DJ would love to see his tenure as Down’s most recent All-Ireland winning captain ended.

comment@gaeliclife.com

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere