By Ronan Scott

PAUL McFlynn has a theory as to why Derry were not more successful in the years after 1993.

The period after that year when the Oak Leafers won the All-Ireland saw the county team come close to success on numerous occasions, and McFlynn was there to see them all as he joined the intercounty side in 1997.

He says that Derry should have won more, and had the potential to do so, but the theory as to why the didn’t has two prongs to it. One is leadership, or a lack of, and the other is prioritising club before county.

McFlynn feels some responsibility for the county’s underachievement, but the interesting thing about his tale is that despite the fact that he has won club and county provincial titles he focuses only on the near misses.

It is a case of if he hadn’t seen the riches he could live with being poor. His formative years began in the Loup. And it is in this period where McFlynn learned that taking part was important.

“When I grew up, playing Gaelic football in the Loup was such an important thing. My father had played and there was such an important tradition there. It was expected that everyone played.

“At times, looking back, there were times I didn’t really enjoy it. Believe it or not, at an early age I felt a lot of pressure to win and compete. I can recall playing games at u-14 Féile level and u-16 being extremely nervous before games. They were big games, they were finals, and we were fortunate to win. However, the emphasis now is on playing and taking part.

“That’s not to say that I didn’t enjoy it. There were great moments. But there were a lot of moments that were pressured.”

The expectations continued from club and into schools level. McFlynn went first to St Pius X in Magherafelt, and then moved to St Mary’s, Magherafelt for his lower sixth and upper sixth years.

Again, the expectation for him to play was there, but he was enjoying himself.

“That was a good time. You are a bit older, and you are aware of other things going on. You can think a bit more for yourself.”

What school exposed him to was top-level coaching. Indeed, for most of his playing career, McFlynn worked with some of the very best managers in Derry and in Ulster.

“I was thinking about the coaches that I have worked with, I was very fortunate. At school there was Henry Downey, then Eamonn Coleman at Derry. Mickey Moran, Marty McElkennon was with Derry as a coach and John Morrison. Some of the ideas that John had, he was ahead of his time. I worked with Paddy Tally in St Mary’s. Then Malachy O’Rourke with Leo McBride at club level, and John Brennan in 2009, and Marty McElkennon rejoined us with the Loup. I have been fortunate to be managed by the best in the business.”

At St Mary’s, Magherafelt it was Henry Downey.

“He took us along with Harry Shivers, God rest him.

“Henry Downey was the manager, I only had him for two years. He had won an All-Ireland a few years before. Having him as a manager and coach was special. It didn’t matter what he said, he had instant respect. He was superb as a manager and a talker. I learned a lot from Henry.

“Henry took us for two years when the Convent. We lost the 1996 final to Maghera but that was a real good spell.”

There was pressure to play football at St Mary’s because the school had a small pick of boys, compared to the likes of Maghera.

“I transferred from St Pius X, Magherafelt to St Mary’s. The first year that we were in MacRory coincided with the first year I was there as a lower sixth. The school was new in MacRory, coming out of MacLarnon, we were not respected.

“The first year we got beat in a quarter-final by St Colman’s who went on to the final. Then in our second year we got to the final. It was that idea of coming from nowhere and trying to gain that respect. Henry Downey was very good at drilling that in to us.”

His favourite year playing for St Mary’s was his last year, in 1996, when he was captain.

They reached the MacRory Cup final, and lost to Maghera, but McFlynn says the year was important.

“The MacRory journey in 1996 was special. I was captain but the school had made a big step forward from where it had come from.

“The boys who were involved in that campaign would still talk about that year. so it is special.”

Football was coming thick and fast and he was playing for school, club and county – and winning.

In 1995, McFlynn also won an Ulster Minor title with the Loup. They beat Bellaghy in the Derry semi-final.

“That was a star-studded Bellaghy team with Joe Cassidy, Paul Diamond, James Mulholland, Ciaran McNally, boys that went on to win numerous championships for Bellaghy at senior level.

“We beat them in the semi-final and then Ballinderry in the final. Ballinderry had Enda Muldoon, Adrian McGuckin, Gerard Cassidy, Mickey ‘C’ (Conlan), again more boys that went on to win numerous championships.”

In Ulster they met and beat Killeavy who had Stevie McDonnell among their number, but they finished with a final win over Clontibret.

At the same time he was playing schools football, he was playing county minor football with Derry.

“It was a natural progression to move through those stages. But I was also balancing that with club.

“I had a lot going on. Three teams at one time. When I look back I feel fortunate to be part of those teams as that I got a lot out of it.”

The overlapping continued as he got past the minor stage as he joined the Derry u-21 panel. At the same time he was playing Sigerson Cup football and he was also called into the Derry senior team.

“They were demanding times, and I was balancing all that, trying to be a student and balancing being a senior county footballer. But lots of boys were dealing with that. That was the journey I was on.”

Playing Sigerson football with St Mary’s demanded similar expectations from McFlynn as he had when he was at the Convent.

“There were only 600 students when I was there, and 460 of them were female. You had a small cohort of boys who were interested in playing football. When you went to St Mary’s and you had any football in you at all, then you were playing. They relied on getting the most out of what they had.

“Even though we had a small pick we were still able to be competitive and put it up to Jordanstown and beat them on occasion. Because we were a small group we had a sort of siege mentality.”

What he remembers is that he was one of many guys who were in the grind of playing for lots of teams. He and many of his county team-mates were experiencing the similar situation of having to tog out for Sigerson teams and also county teams.

“Our lives revolved around training, playing, trying to get some sleep and a wee bit of partying in between. Then you are up at it again. There were time in periods where I felt physically exhausted.

“There were times when I’d be training on Wednesday afternoons at St Mary’s and then getting into a taxi to go to Owenbeg to get to training that night. Things that you would let boys or expect boys to do. Back then if you missed training they would say ‘ah he’s resting’, as if you were bluffing or taking the easy way out.

“I think there is a greater awareness of sports science and recovery. That’s not to say that the boys who were over us wanted to flog us into the ground. Maybe it was an internal pressure that we felt, that we were worried that if we didn’t go there would be ones talking about us. I know there were other lads who felt that, fellas who were with Armagh, Down, they were all coping with that.”

McFlynn’s coaches at St Mary’s were first Mark Barr and then from his third year onwards it was Paddy Tally and Mark. He said that they didn’t put the players under any pressure

“They were brilliant. If you went to them and asked them for a day off they would have give it to you. And I did ask them. But because the school was so small, and you were trying to achieve something together, that work is built on the pitch training together. I am sure that across at Jordanstown and Queen’s boys felt that as well. That’s why the GAA moved towards looking at burn out.

“I enjoyed my experiences, and I think that playing at Ryan Cup and Sigerson Cup is a great level to play out. I have no doubt that playing at that level certainly brought me on.”

Those years were important in forming a winning mentality in McFlynn.

In his early 20s, after playing for St Mary’s, Magherafelt, the Loup and St Mary’s University, Belfast, McFlynn understood the dynamic of siege mentality. Those three groups, and the teams within them were smaller and closer knit groups than their neighbours, demanded participation and dedication.

Part of this formed McFlynn the player, who was determined to work for his team-mates.

“We certainly had a siege mentality in St Mary’s, Magherafelt, and in Belfast and at club level. The Loup had come from being a junior club. I remember my father playing junior football and winning Junior Championships. It was not that long ago, they were in Junior in 1989 and then were up in Intermediate in 1994, then my first year in senior football was the first year that Loup was in seniors.”

So turning up was important, and in those years McFlynn was in demand, He was playing minor and senior football with his club, schools football and county minors.

But playing for his club at that point in time was so important because they were on the big stage.

“We were coming up against the likes of Lavey, Bellaghy, Dungiven and Ballinderry, the teams who had been there for a long time. They were established teams. It took us a long time to establish ourselves and earn respect. Clubs that are up there want to keep new clubs down. They want to keep them in their place. We found that there was that and it took us some time to come through.”

Those experiences brought a steel to McFlynn the player, but it also made him want to progress and play at the higher level.

That level was senior county football.

“I loved playing for Derry, it was a great honour. I came onto a squad after 1993. I had followed Derry everywhere with my father. I was looking at them boys at 15 years of age winning an All-Ireland and I thought that I’d love to play for Derry. I never thought that four or five years later I would be on that panel. It came about a lot earlier than I thought.

“Going in to play alongside them boys, who were my idols, was important. But I was also coming into the team with a really good group of the minor team that had got beaten in the final in 1995, and then the u-21 team that won in 1997. So there was a real good group of talent coming through hooking up with the All-Ireland winning team. That’s why I enjoyed it because we were playing at a real high level.”

In 1997 he won the All-Ireland U-21 title with Derry, beating Meath in the final. A huge stepping stone for McFlynn and one that led him onto the senior team in 1998. But he didn’t really stop and think about what a step it was for him.

“You didn’t realise at the time how fortunate you were to be coming in to a team playing alongside Henry, Kieran McKeever, Anthony Tohill, Joe Brolly, Fergal McCusker, Gary Coleman, Dermot Heaney. All those boys were there, Boys who had been there and done it. They were established.”

Those players taught McFlynn about the effort that has to go into a team for it to win.

Henry Downey, who had taught McFlynn at Maghera, was a shining example of what it took to be successful.

“Downey was the sort of boy if there were 15 cones in a line, and you were told to run around each one and come back, he went round each one. He never cut a corner. He didn’t go over the top of the cone, he didn’t take any short cuts.”

Looking back on it, McFlynn sees that what made those players special was their focus.

“Those boys were hell-bent on succeeding for Derry. They were proud club players, but they wanted to win with Derry. They weren’t putting club second, but maybe when they were trying to win that All-Ireland the club was coming second.

“There was a real determination.”

McFlynn remembers an example of that determination, and the willingness to put county first from 1997 when he had just joined the squad.

“Brian Mullins was the manager in 1997. Myself, Enda Muldoon and Sean Donnelly were on the panel and we were travelling up together. We knew we were going to be on the bench, and we weren’t going to make the breakthrough. But we had club games that weekend. We were told that no one on the panel of 30-odd were allowed to play any club games.

“I wasn’t going to be in the reckoning for the game. I remember playing the club game for the Loup against Magherafelt, which would have been a big rivalry. It was a Sunday game and we won it.

“I remember going to training on the Tuesday night and going into the changing rooms. Enda and Sean played their games as well. So we went in and sat in the corner. A certain senior player, I’ll not name who, said, ‘there’s the scabs’.

“Boys were laughing and joking. Then they said we were in bother. Then Mullins walks in. We were changing. Mullins says to us, ‘Did you boys play with your club at the weekend?’ we said we did.

“Mullins said, ‘right, I think you should do the honourable thing lads, see you later’. So we packed up and went home.

“When you look back, when you understand what he was trying to achieve, he was right. We had broken the rules. There were other boys who weren’t going to be in the reckoning, but they didn’t play with their clubs. They probably took a lot of flak. But it is very hard to manage.

“So then in 1998, I toed the line and we won an Ulster. Tohill and Henry and them boys fully supported what Brian was doing. That’s the mentality that you need.”

1998 is his most successful year as that was the season when he won his one and only Ulster title, the last one that Derry have ever won.

“That was a great year. That’s the one you have to think of as the best. We did win a National League in 2000. That was great, but winning that Ulster title was great. There was no backdoor then, it was straight knockout.

“So that was my favourite year.

“What I enjoyed about it most was being fortunate to play for Derry. There are a lot of hardcore Derry fans that you bump into, and they would talk about Derry games that I played in and they remember more about the games than I do. Being able to represent county at minor, u-21 and seniors.

“But now l look back on it and think about what I won. However. I do think that I could have won more.”

From a club perspective, McFlynn had similar feelings.

“We were beaten in three finals, we played in five county finals and won two. So I think that three out of five would have read better than two out of five. You are always thinking about what more you could have done. You talk to other players and the ones they have won, they are tucked away. But the ones that got away are the ones that you focus on.”

In 1999, Mullins left the Derry set up, and Eamonn Coleman arrived as manager. Here McFlynn had his next experience of working with a legendary manager.

“That year we got beat by Armagh in the semi-final. They beat us by a point but I had a chance to score a point at the end but missed it, hit it wide. So we had a team meeting the following year. The year had went okay for me in 1999 but I remember the meeting the following year, 2000, in the meeting he (Coleman) was going round singling out boys.

“He went through the younger boys and he said ‘look, the time for minor football is over, and u-21 football is gone. The time for pussyfooting about is over. It is time for you boys to do a bit more and step up’. Eamonn put it across in a more colourful way. That was a real introduction to him.”

This was the man that had led Derry to an All-Ireland, and McFlynn was learning how the wee man from Ballymaguigan operated.

“I remember the day we played Antrim that went to a replay. The day that Tohill caught Shenny McQuillan’s shot above the bar. On that day, none of us played anywhere near where we should have. I did okay, but on the Tuesday night, we were about to head out to training. Eamonn says, ‘where are you going? Sit down there’. We knew the hair dryer treatment was coming.

“He went round everyone, and had a go at everyone. He got to me and he says ‘where were you at on Sunday?’ I just looked at him. I didn’t want to say anything back to him. Even if he wasn’t talking to you, you wouldn’t want to look up, because if you caught his eye, he’d remember something else he’d give you a touch about. Everyone just stared at the floor.

“But then he laid it on thick. He laid it on about performance, and he said I never got past a gallop.

“It is funny, you had boys like Henry, Anthony Tohill, none of those boys answered him back.”

McFlynn said that Coleman’s hold of his players was special.

“If someone else had said the things that he said, it would have worked the other way. You would have gone out not wanting to do it for them. He could say those things to you but he was good at building you back up.

“I remember that night walking past him, he caught my eye, and I looked at him and walked on. Then out on the training pitch the session started, and he would be over with you. He would say, ‘I don’t like saying those things to you, but I know there is more in you’.

“He gave you the touch in front of everyone, but then he was over bringing you back up. But he did the same with everyone, he went round and spoke with everyone, every player building them back up.

“He was a psychologist though maybe he didn’t know it. He was good at getting stuck into you to make you think but then building you back up again.

“No matter what he said to you, you respected him. And he was telling you the truth. He was the type of man that you wanted to play for. You wanted him to be happy, and at the end of the game you wanted him to look at you and be happy with you. I don’t know how managers do that.”

So in 2000, McFlynn was particularly pleased with himself as Coleman made a specific move to show his trust in the Loup man.

“I remember one night we were training in Owenbeg. He came over to me and he said,’I am making you vice-captain this year’.

“To be honest I was shocked. It wasn’t even in my head. So Tohill was captain and I was vice-captain. Because Anthony was there, and he was the man that was leading.”

And when McFlynn looks back on his career he sees this as a turning point in which he should noticed the change.

“I was still vice-captain in 2003 and Enda Muldoon was captain, so I did feel the responsibility to move the thing forward. To be honest, it is one area that I look back on with regret.”

McFlynn said that he will often talk to his former team-mates like Johnny McBride and Enda Muldoon about their experience as players and what they should or shouldn’t have done to lead the younger players on.

There are regrets, and one of those is focused on the 2001 season when Derry lost to Galway in the All-Ireland semi-final.

“I have chatted to Johnny (McBride) about this, and big Enda (Muldoon), we look back on our Derry campaign, we got to an All-Ireland semi-final in 2001. Galway beat us in a game that we should have won.

“We were five up with 10 minutes to go. That game still gives me nightmares. There are moments when I will just stop and think about that game. We should have won it.

“We were the better team on the day. Then, while it is hard to say, we always had the better of Meath back then (Meath played Galway in the final). They were the one team that we were able to beat. We beat them in the National League final.

“So I think we would have won it, but it was Galway who beat us and then beat Meath in the final.

“From then on, from 2002, we didn’t push on.”

They didn’t push on but McFlynn also points out that there were some significant individuals who left the team after that year who were hard to replace.

“We lost a serious calibre of players. We lost Henry, Kieran, Fergal P, Gary Coleman, Dermot Heaney. We lost them within two or three years. For any county it is hard to soak up that loss.”

McFlynn said the attitude changed too.

“I don’t think we knuckled down as we should have. We had reached the All-Ireland semi-final the previous year but we didn’t take it seriously the way we should have.

“We had a serious team.”

They had Fergal Dohety, Gareth Doherty, Conleith Gilligan, Enda Muldoon and a host of other top players in Derry.

It didn’t work out for Derry, and Eamonn Coleman left the set up and in came Mickey Moran and John Morrison for the 2003 campaign.

“In 2003 we should have had Tyrone beaten in Clones. But it went to a replay and they hammered us in Casement Park. That year, there was bad news when a cousin of Kevin McGuckin passed away. He didn’t play. That news coming through put a different slant on that day, and Tyrone came out looking for revenge and they hammered us.”

Dublin beat Derry in the back door in 2003 and then Anthony Tohill retired.

At this stage in his career there is another turning point worth pointing out, and it is the impact of club on the county team.

At club level, 2003 was a good one for McFlynn as that was the season the Loup won the Derry and Ulster Championships.

The previous year they had lost the county final and they were at a low ebb.

Malachy O’Rourke was in charge and he led the team to glory.

“His ability to instill in us the belief that we could go on and win things did not happen in one night. It was a slow drip feed every night, from the first night he took us on. You could see it gradually build up.”

There was another tenet that O’Rourke followed that McFlynn felt was important to the Loup’s success.

“He said that number 35 was as important as number one. There are stories over the years of boys who were a sub on our reserve team, they got the same attention as everyone else. There are other managers that didn’t work like that. Not that they meant to, but players see that. If a player got injured they would get the same treatment in terms of physio, or Malachy would be ringing them that night, the next morning. He’d do the same for them as he would Johnny McBride.

“There are managers who would set out to do that, but they wouldn’t do it. Malachy did.”

And there are reasons why he does that.

“Work-rate was a big thing for Malachy. You can see that with his teams. But you don’t get work-rate if other things aren’t right. He was very good at that.

“Leo McBride was with him and he was a fantastic trainer.”

O’Rourke put the effort in, and he expected his players to do the same. McFlynn remembers how Malachy would not accept people taking short cuts.

“In 2005 I pulled my hamstring and I missed the opening championship against Craigbane. I remember I had to go to a wedding in Omeath the day before a game. I wasn’t going to be playing in that game. I was always going to go to the game. I went to the wedding mass, drove up the road to stand and watch the game in Magherafelt, then drove back to the wedding in Omeath, then drove home again. That was expected.

“Another story like that was Brian Lavery, who was injured one time for a league game. He rung Malachy up and said to him ‘look Mal, I am injured, we have that league game’, he was suggesting that he didn’t need to go to the game and he wanted Malachy to let him off.

“Malachy said to him, ‘sure, I’ll see you up there’. There was no such thing as treating anyone differently and everyone saw that.”

McFlynn said that while there was a focus to the football side of things, Malachy also was a people person. He got to know players outside of the game and would know what they did for a living.

It was perhaps that caring side of him that made players want to play.

“He wasn’t inflexible. If boys had an issue or problem he would deal with it. If he knew you needed the time off he would give it to you. But if boys were taking the easy way out then he wouldn’t let you away with it.”

There were elements of O’Rourke that reminded McFlynn of Coleman, in particular how the manager made the players want to play for him.

“O’Rourke had that thing where you didn’t want him to be disappointed with you. He didn’t roar and shout. But his body language told it. You would know by what he didn’t say to you.

“O’Rourke’s attention to detail in terms of the psychology was the biggest thing.,

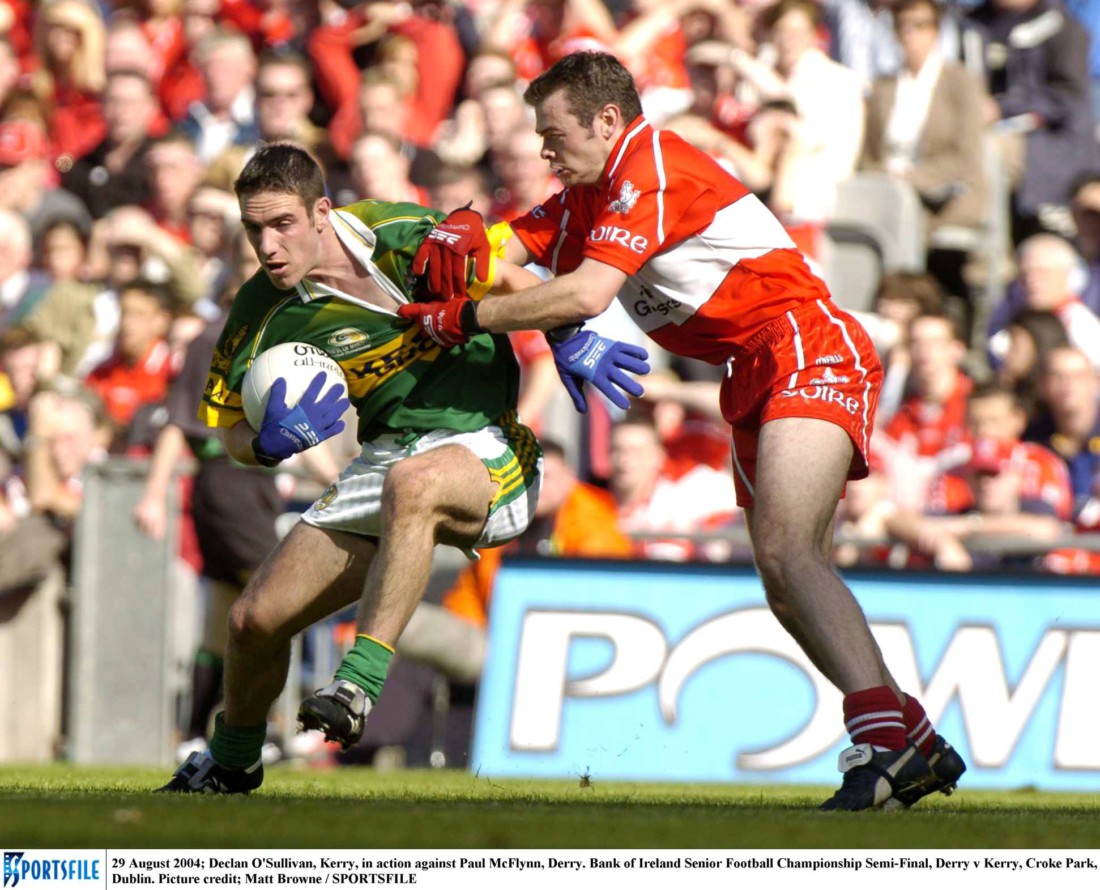

But in 2004, Derry would go on a run all the way to the All-Ireland semi-final. Yet that was a missed chance, and McFlynn thinks that they should have achieved more.

“I do look back and think that a combination things happened. There were structural issues at county board level that could have been put in place for the panel. But that is not getting away from the fact that myself and other players did not do enough to bring it forward and want it enough.

“Myself and other senior players, have regrets that we didn’t win more. That team didn’t even win an Ulster title. I was fortunate to win one in 1998 but I would never have dreamt that would be my last.”

It is interesting that McFlynn says that the issue of county board support must be part of the reasons why the didn’t win more.

“It’s been brought up before. But maybe we could have got more from the county board. We were seeing what Armagh and Tyrone were getting. Maybe we were at fault. Maybe we should have demanded more. It is hard to pin-point. But I wouldn’t put the blame outside ourselves. We trained away yes, but there was more that could have been done.”

It is the early 2000s and the club success at that time that McFlynn suggests played a role in the lack of success for Derry. While the Oak Leafers did reach the All-Ireland semi-final in 2004. He suggests that players in the county had put club first. This is in contrast to how the men in 1997 and 1998 under Brian Mullins had been thinking. But arguably the players had good reason to be thinking about their clubs.

“Ballinderry had that success at All-Ireland level. We (the Loup) won Ulster in 2003. It has been said that in Derry players might have put more into their club. There might have been an element of that, but it wasn’t a case that we said we wanted to put more into our clubs.

“I think there was a competitive edge in Derry. When Ballinderry won that All-Ireland, clubs all around, Bellaghy, Dungiven, ourselves, Slaughtneil, all were thinking that we could do that. Perhaps more effort was put into club in the background. That’s not to say you shouldn’t do that. But that did kick in for a few years.”

McFlynn points out that that Ballinderry winning piqued everyone’s interest. Bellaghy had won three Derry Championships in-a-row, but not the All-Ireland title so he thinks they must have been thinking that they could do better and he freely admits that the Loup watching their neighbours win an All-Ireland focused their minds.

“We had a breakthrough when we won the league for the first time in 66 years, so that was a breakthrough and then we went on to win Derry and Ulster the following year.

“And there was a spread of winners after that, Slaughtneil in 2004, Bellaghy in 2005, Glenullin in 2007.”

So with all those things added up, intercounty retirements, club focus, it all led to the Derry county team underperforming.

“I don’t think we recognised it at the time. We were going to training and working hard. But it is only when you stop playing, and look back you maybe see the way things progressed, then maybe you see the way things could have been improved.”

“I enjoyed all the years I played for Derry. I enjoyed the training and the competitive element to it right through to my last year in 2006 under Paddy Crozier.”

The regrets are very evident to McFlynn even now, so many years after he retired.

“We went into the team in 1998 with players who were established and took us under their wing. But the fellas who came after, we underachieved. We didn’t take it forward how we should have.

“We could have pushed on but we didn’t. I imagine that in Tyrone and Armagh, there were players there who were pushing them on. They had the full focus on county when they were there. Then the same for the club. But Derry there was an overlap.”

McFlynn stopped playing county football in 2006.

At the start of his retirement he dealt with the break okay.

“I toyed with the idea of going back in 2007, but injuries and things like that put paid to that. For a year or two, when Derry were playing I was thinking that I should have been out there. But that goes relatively quickly. Now, looking back, in 2006 it is a distant memory.

“I think perhaps, maybe it is when you get into your 40s other things take over, family and that.

“Then I tend to look back on sport as something that was good, but you realise that other things are more important.

“When I was playing for Derry it was the be all and end all. But now, if I were to do it all again, I would maybe have a more relaxed approach to it. Maybe that’s easier to say now that time has passed, and you are wiser, or you think you are a bit wiser.”

Club still provided him with an outlet. And he was there in 2009 when the Loup won their second title.

The manager that year was John Brennan, the Lavey man who had enjoyed club success with his own club and also in Antrim.

“We came from nowhere that year. We were bottom of the league that year. But there was an eight-team league. You played everyone twice. It was a war of attrition. We were bottom of the league but Brennan said, ‘never worry about league football boys’. His phrase was ‘leagues are for playing in, championships are for winning.’”

McFlynn soon discovered that Brennan was a man who understood football brilliantly.

One of the games when that was evident was the Loup’s semi-final against Bellaghy.

“They were our bogey team at the time. In the 2009 we changed our whole tactics. John looked at the videos and he said we were going to change.

“I had played at centre half-forward all year, but he switched me to midfield along with Johnny McBride. We were up against Fergal Doherty and Joe Diver, so there was a bit of a height disadvantage. Brennan said we were going to use short kicks. Our ’keeper Shane McGuckin was fantastic and we worked on short kicks for that game.

“That day Bellaghy weren’t ready for it. I think we hit, across both halves, we hit 14 short. We used Celtic Park really well. Shane was able to chip a 35-yard pass into a man’s chest. That came from John Brennan and Marty McElkennon.

“Brennan was also great at matching men up. He never got any of those calls wrong. People said things about him.”

Brennan is perhaps known in Derry for being wild on the sideline, but McFlynn explained that the man is not as wild as you might think.

“He might have got a reputation for losing it on the sideline, but he never lost it as much as people thought he was losing it.

“He was much more controlled. Sometimes it was deliberate to get inside manager’s heads. He has them thinking about things, getting annoyed at him, trying to engage with him. But he’s not thinking about that, he’s thinking about what is going on on the pitch.”

McFlynn said that Brennan’s ability to make the right call was uncannily good. The best example he has for that was in the 2009 final.

“There was a lad playing for us called Enda McQuillan who hadn’t actually made the championship panel. He was a great player for us down the years but had had a few injuries that year and was on and off the panel.

“Before the county final against Dungiven we were playing in-house games. Brennan came to me and he said: ‘I think your man there could do something for us on Sunday’.

“I said ‘who?’, and he said ‘McQuillan, he looks really sharp. The way he is he is the type of man that would get you a goal’.

“If you know anything about that final you know that Enda McQuillan came on and scored the winner.

The game was in the balance, and Joe O’Kane went up the pitch and he hit it. We always keep Joe going that he went for a score, but he says it was a pass. The ball went in, bounced between the ’keeper, Enda ran 40 yards and the ’keeper came out and got caught in no man’s land and Enda fisted it over his head to the net.

“That was the first bit of championship football that he got, and he got that goal that won it for us. Brennan had said that if you put that man on he would get a goal.”

McFlynn said Brennan was like Malachy O’Rourke and Eamonn Coleman in that he was able to get the best out of his players.

“We beat Dungiven in the final. Johnny McBride and I were midfield that day marking Paul Murphy and Darren McCloskey. It was a big task but Johnny and I fared pretty well. We broke even if not a wee bit more. So we were happy and after all the celebrations we were back out training on Tuesday night.

“Brennan walked past the two of us and didn’t even stop, but he says ‘Okay on Sunday boys, but we’ll need a bit more out of you the next day’. He said it so quickly as he was striding past.

“He was just putting something in your ear, in your head, that if you thought you had done enough you were wrong. There had to be more.

“If someone else had come out with the things he said, you’d have been liable to tell them where to go, but because it was him you wanted to do better.

“Whatever it was about him you just wanted to please him. It is strange to articulate. Anyone you talk to about him felt the same.”

Before Brennan came into the Loup team, McFlynn had an idea of what the man would be like. Yet the reputation was different than the reality.

“John is a very articulate and a deeper thinker than people give him credit for. I got to chat to him about different things, personal stuff. He is very much attuned to what is going on around him.”

While Brennan was McFlynn’s final manager, another man who was attuned to what was going on around him was Johnny McBride.

The one constant in McFlynn’s life has been McBride. They were at school together, played county and club together, and in the Brennan days played alongside each other at midfield.

“There is not a day went past when we were playing for the Loup or Derry that we would have been on the phone to each other.

“Normally when we drive to work or on the way home we would ring to catch up, usually about a match or what was going on. You’d often ring up and discuss about what was going on if a team is being picked, or what was happening at training.

“Even since we retired from Derry and the Loup we’d still ring up and discuss about Derry and the Loup. That keeps going on.

“It is a friendship since we were u-12. He is a year older than me. And in Derry, when I was talking about us not pushing things on, he would have been the one boy who would have been leading from the front. He would have had the similar mentality to Tohill and Downey, he wouldn’t stand for nonsense.

“He would have spoke up about things that other boys wouldn’t have. And he maybe didn’t get the support that he should have got for that.

“Even at club, if he is telling you to do something, then you can be sure that he is doing it and more.”

McFlynn saw first hand how McBride would put personal friendships aside for the good of the team.

“If he doesn’t think boys are putting the work in then he is not afraid to say to them in the circle.

“I recall a story when we were training with Brennan, a half eight gutting match on a Sunday morning. I can remember feeling like I was going to be sick. We played an in-house match. The standard of the game was not too hot because boys were wrecked. I noticed that Johnny was not happy.

“We got called into a circle. Johnny had got word that boys had been drinking the night before. The boy was talking, and Johnny nailed him in front of everyone. He basically said, ‘if you are doing that then we may not turn up. If you think you doing that then you don’t have the ambition.’ He said if you want to do that then there’s the gate and don’t come back. he wasn’t even captain.

“That started an argy-bargy. Other boys were sticking up for this boy. Some of the rest of us stood up for Johnny. Then a row started. Brennan stood back and let it go. He probably thought we should sort it ourselves.

“Johnny was challenging a boy that he was friendly with. He wasn’t even captain. He had captained right through, but even when he wasn’t captain he led. But there weren’t enough like him.”

2009 was McFlynn’s last year of club football. He says that the challenge of mixing personal life and football became too much of a challenge at the end.

“The way things were going at home I couldn’t commit. Our second child was born on the 29th of October. We were due to play Derrygonnelly on the Sunday. He was born on the Thursday, but Brennan wanted a meeting and a kickabout on Friday. I said to John I couldn’t go because of the new born. But he said, ‘quick meeting Paul’.

“I went, the kickabout about was longer, the meeting was longer. I drove to Antrim and closing time was over. I was banging on the door. One of the nurses let me in. I remember my wife shaking her head. You talk about feeling bad.

“I had two boys, one with special needs (one of Paul’s sons is autistic), so that was it.

“I probably could have went back two or three years later when things settled down, but I just couldn’t because I hadn’t played.”

So if there is a conclusion to draw from this it is that for a man to succeed in football he must be committed. McFlynn saw that throughout his entire life.

He loved his football, and still continues to play recreational reserve football for the Loup, but his approach to the game has changed from when he was younger.

“Now I have got my own boys, if they said to me that they didn’t want to play anymore, my first reaction would be that I want them to stay at it because of the benefits that they get out of it because of the socialisation and the team-mates and friends and camaraderie.

“But if they said they wanted to do something else I wouldn’t be bothered.”

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere