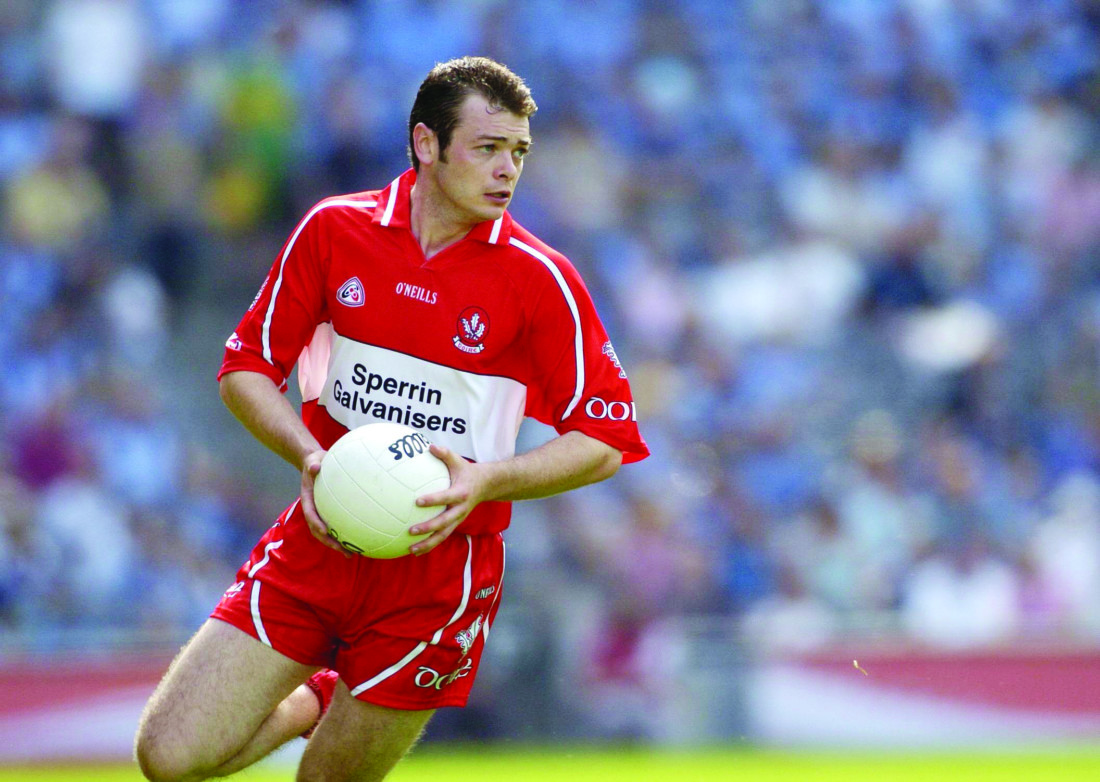

Paul McFlynn was a mainstay in the Derry senior team for ten years and part of Loup’s success story from underage promise to Ulster senior champions. He sat down with Michael McMullan to recall a decorated career.

PAUL McFlynn talks about football in the same manner he played, with utter calmness. The words and memories mirror his use of the ball, measured and on the money.

In terms of playing the game, the interest came from both sides. He couldn’t miss.

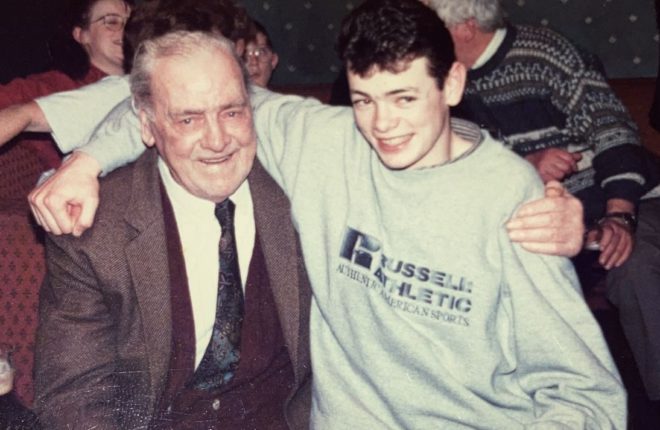

His mother Rosaleen’s father, Laddie’s Francie Quinn, won the O’Neill Cup three times with Moortown. Sadly he passed away within weeks of a much cherished photo (below) with his Grandson Paul after Loup won their second Ulster Minor title on New Year’s Day 1996.

Bernard McFlynn won two Junior Championships before hanging up the boots after winning the Intermediate title in 1994. That same year, he played at full-back as Loup Reserves won the Graham Cup with his 16-year-old son Paul at centre back.

“Back then, he was taking the kick-outs,” Paul recalls of his father. “I was looking for kick-outs and calling ‘Da’ and the Magherafelt boys were starting to laugh, so I changed and started shouting ‘here’ and running for the ball.”

Growing up, everywhere Loup seniors were playing, Paul would be there. He was standing in the rain for the 1989 Junior Championship final win over Coleraine. In the days before catch nets, he’d be fishing the balls out of the river at training.

Football was an obsession from very young, glued to the Sunday night highlights in the days when live games were a rarity.

PRECIOUS MEMORIES…Paul pictured with his grandfather Francie Quinn at Loup’s 1995 Ulster minor celebrations, just days before he passed away

His first visit to Croke Park was the 1987 All-Ireland semi-final defeat to Meath and the limited involvement of a strapped up and hamstrung Dermot McNicholl.

Little did he know he’d be back in the first season of a 12-year county career that began with a run to the 1995 All-Ireland Minor final.

It would have to wait. Colum Rocks was at the forefront of a revolution that would see Loup dominate Derry underage football, laying a solid foundation for their senior success.

It didn’t begin well for McFlynn. Aged just eight, he found himself making up the numbers as Loup u-13s were handed a 50-point pasting by Castledawson.

“I remember going with a white plastic bag…I didn’t have a gear bag,” he recalls of his Loup debut, at corner-forward against players twice his height.

“The ball never came up too much and I remember my Ma asking me how I got on when I got back and asking me had I touched the ball.”

Seated in a quiet corner of the cafe in Maghera Garden Centre, McFlynn chats freely about how things have changed from his own childhood.

Married to Aideen, their four boys Ger, Rory, Dara and Leo have them on the move to various activities and sports, the more the better. Variation is king.

Growing up in the late eighties, his the focus was narrower. Lindsayville green in Ballyronan was the sporting epicentre. School was followed by a quick bite before scampering out into an arena where nine year-olds went into battle with those up to twice their age.

Aside from the odd row or burst ball, it all ran as smooth as it needed to be. Teams were picked for games up to 12- or 13-a-side and everyone played away.

The summer saw it radically step up to a full day of action in three chunks, broken only by lunch and dinner, with an even mix of Gaelic football and soccer.

“I used to leave in the morning with a ball under my arm and I had to be back for lunch, there were no phones or communication,” McFlynn fondly recalls.

It was the same in the evening, with a return for supper and a wash. He’d delve into the tennis highlights from a day at Wimbledon, hit the hay and get up the next day. And so the cycle continued.

“Looking back, you and think you’re exaggerating but that’s what most of our days involved,” he added of a football routine Hugh Brady added to in Loup PS.

“We grew up in Ballyronan and it was really cross-community before we knew what the phrase cross community meant,” McFlynn added, pointing to how some protestants would go on to play for Loup.

There was never a question of why they were at a different school; it was just about football, craic and plenty of both.

Drivers coming into Lindsayville expected a ball to bobble across its path. In time, a set of wooden goal posts were erected. Their Mecca was complete.

Beside it was the Ponies’ Field, with a tidy gap in the hedge, big enough for the smaller lads to retrieve any stray balls. One day, Jarlath Martin – not able to get the words out quick enough – called on McFlynn to do the needful. On the spur of the moment, he called him Paddy Finn, a quick-fire attempt at Paddy McFlynn, his Granda’s name.

“I can remember crawling through and getting the ball. When I came back out, some man said: “look, Paddy Finn’s back” and that was it, that’s how it stuck and that’s from I was about nine or ten,” McFlynn explains of a nickname that stands the test of time.

Colum Rocks lived nearby. He would look on, without getting involved, at all action. The raw material was there. By 1988 the wheels of change in Loup’s underage began to whirl.

Ronan Rocks, Marty Bradley and Kevin Ryan were key players on a team that won the clean sweep growing up, all the way to Ulster Minor. Younger players like Paul McFlynn were on the fringes, getting action here and there, while taking home silverware at their own age.

Early on in the project, Dublin stars John O’Leary and Noel McCaffrey were involved in a coaching session up in Loup pitch.

“It was Colum who got them up and that was one of my early recollections of training,” said McFlynn, who would win Derry and Ulster senior medals with his younger brother Shane in attack.

The numbers flocked. Rocks’ work van and estate car were always stuffed to the gills on the way to games.

“I remember going to games and counting 12 getting out of a car. I was the smallest, so I was always on somebody’s knee, squeezed in somewhere,” McFlynn recalls.

“’Paddy Tight’ (McVey) had a big red Sierra and we went to Bundoran one day and 13 got out of it and I was in the boot with rarely room to move but you were glad to get going.”

As the coaching programme grew, Colum got more people involved, like his brother Eamonn and Martin Gallagher who managed the 1995 Loup minor crop.

“Anyone can train a team but coaching is a different matter,” McFlynn said of Colum being “ahead of his time.”

WINNING FEELING…Colum Rocks (second from left) and Paul’s father Bernard (middle) celebrate success with Loup

Balls and bibs were plentiful. There were never any queues waiting on a touch, McFlynn’s pet hate, and kicking was high up the priorities.

“I remember him teaching us about our head, our hands and our feet, about our body position and kicking off the laces,” McFlynn said of the principles he relays coaching his son Dara’s team in Glen where he now lives.

They followed him into a PE teaching career in St Louis, Ballymena and later his current role as PE Course Director of the PGCE PE Lecture at Ulster University.

“His drills were multidirectional and it was all about making decisions…he thought about what he was doing,” Paul added, also referring to running sessions that had them fit and ready for the challenges ahead.

Before Colum’s death in 2018, he was present at a reunion of their minor teams. The respect in the room said everything of the legacy he left on the club and the contribution it made of senior success.

“No matter how many words I would say about him, it was very hard to put what he did into words to do him justice,” McFlynn said.

“You’ll never be a prophet in your own land and I don’t think the hierarchy or the people of the Loup fully appreciate what he did.”

With less than a handful of days remaining of August 1994, Paul McFlynn was at an educational crossroads. St Pius, Magherafelt, where he studied for five years, didn’t offer A-Levels.

St Patrick’s, Maghera was initially lined up, but Loup teammate Brian Lavery was adamant he should join him at St Mary’s, Magherafelt who were dipping their toes into the MacRory Cup for the first time.

“He literally tortured me,” McFlynn laughs. “He hadn’t the driving test at the time and he’d call down to the house in his tractor.

“He was talking about all the players the Convent (St Mary’s) had and how they could be competitive in the MacRory.”

Studying the same subjects, a later bus in the morning and home earlier in the evening swayed him towards St Mary’s.

“I went the day before I started to get a uniform and that was the start of me playing in the MacRory,” McFlynn explained.

They narrowly bowed out in the quarter-final at the hands of a St Colman’s, Newry team beaten by Maghera in the final.

Magherafelt reached a first ever final 12 months later, but McFlynn’s 1-1, as captain, wasn’t enough to stop Maghera completing three-in-a-row.

By that stage, his reputation was growing as he embarked into a second year as a county minor but he needed a slice of luck to make the panel in 1995 as Derry went all the way to the All-Ireland final.

Standing on the sideline, 45 minutes into the final trial, he felt he hadn’t done enough the first day. Thankfully, someone got injured and in he went.

“Paddy Crozier sent me on and the ball stuck to me…it was magnetic. It was one of those days, no matter where the break was it was dropping into my hands. I got a serious amount of ball in that 15-minute spell.”

Kick-outs were landing on his side and he managed to ghost upfield to tag on a point. Out of the side of his eye, he would see Chris Brown and his management team pointing and talking. He knew he had made the cut.

After winning Ulster, they beat a fancied Galway team in the All-Ireland semi-final with John Divilly, Derek Savage, Michael Donnellan and Pádraic Joyce on board.

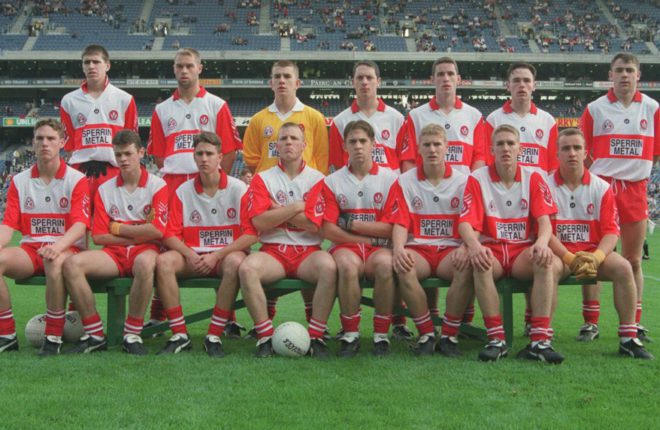

MINOR MATTER…Paul (front, second from left) ahead of Derry’s 1995 All-Ireland minor final defeat to Westmeath

It counted for nothing on All-Ireland final day when they were ambushed by Westmeath, a defeat that still cuts deep. Now an avid All-Ireland final attender, McFlynn can always relate to minors sinking to their knees in defeat.

“It surely was a case of complacency going into that game. It wasn’t deliberate, but it set in and if we had played them another 19 times we’d have beat them,” he said of a team that included future senior Derry teammates Johnny McBride, Paul Diamond, Ciaran McNally, Enda Muldoon and Joe Cassidy.

With Loup now in senior football, 1995 was McFlynn’s debut season, taking him to a semi-final defeat to eventual champions Ballinderry and a second Ulster Club Minor title.

It was “probably the biggest” year in his development with the confidence of the run with Derry minors. Coming up against quality players forced him to deal with an increased speed of thought against quality operators.

Derry were back in the Ulster final the following season, losing out to a Donegal team after a replay that narrowly lost out to eventual champions Laois.

It wasn’t long before Brian Mullins sent word and he was invited to join the Derry senior panel.

Totally shocked at the call, shortly after starting St Mary’s University after the summer of 1996, he found himself sharing a taxi with Ronan McGuckin all the way to Owenbeg.

It was the pre-Christmas National League phase with young hopefuls joining the established players not granted the downtime early in the season.

“I was still 18 and thinking I was far too young and light for this,” he says, looking back on those early days.

One night he was going through on goals, soloing at his leisure before kicking for a point.

“Just as I kicked the ball, I was totally and utterly emptied…I never got a hit like it,” McFlynn said of his welcome to the real world of inter-county senior by Kieran McKeever, someone who always wanted to get the best out of him.

It wasn’t dirty in any way, just tough and a statement, a reality check of what was coming down the tracks over the next 10 years. It wasn’t personal. Everyone got the same treatment. It wasn’t underage anymore.

“I remember getting hit and I don’t know where the ball went, if it went over the bar or not. It was a wet and horrible night and I was winded, one of those ones where you can’t get a breath.

“When I got up I was wheezing and thinking somebody would come over and nobody was near me and the game was going on.

“I had a lot of time for him (McKeever), Tohill and Downey, boys like that, but they weren’t there to babysit you. That was the one shock, going from an underage game into a man’s game and me only a boy.”

Billy O’Shea was fresh from helping Laune Rangers to the All-Ireland Club title and McFlynn held him scoreless on his Derry debut, a 1-12 to 0-10 defeat to the Kingdom in Killarney.

“I was happy enough that day. Mullins came over to me telling me I did well,” McFlynn remembers.

The following week Mullins handed him a different and very unlikely role at corner-back on Jason Reilly in a heavy defeat. Reilly had the ball over the bar within 37 seconds and McFlynn was replaced at half time. Even the advice of Sean Marty Lockhart in the other corner couldn’t save him. He was a duck out of water.

“I wasn’t the quickest but out in the half-back line I could read the game,” he said. “Marking an inside forward as quick as that, I remember marking him as tight as I could and being about half a yard behind him all the time and he got the ball…clean roasted.”

Mullins called him over the following Tuesday at Owenbeg. It would be the last time he’d be in the corner. It was an experiment.

“It told him I could’ve told you that beforehand,” McFlynn now jokes. Corner-backs and half-backs were like chalk and cheese in that era.

He tasted more league action but an unused sub on the matchday panel on Ulster final day was the closest he came to championship action. It was a day when Jason Reilly ironically hit the net to sink Derry with the Breffni men needing a disputed Raymond Cunningham ‘point’ to land the title.

The year did finish on a high for McFlynn and many of the 1995 minor team as they wiped the floor with everyone on the way to All-Ireland u-21 title, beating Meath in the final, who had a handful of All-Ireland senior winners in their ranks.

“That was another big surge in my development. Even though I had another two years at u-21, I was playing senior and getting a lot of exposure,” McFlynn reflects.

“It was a great year and we had a serious team and never went into the last minute of any game needing a point or two, we won the games fairly comfortably.”

The 1998 Ulster Championship saw Mullins hand McFlynn his championship debut in a victory over Monaghan as they embarked on their journey to the Ulster title. It was a new level and the pace of the game was another reality check.

“There was a focus on having to concentrate all the time. I remember boys telling the younger ones to keep focussed and keep our heads in it,” he said.

Being switched on at any level was important, but there was no safety net at the top level and more accountability. Quality players could put your light out in the blink of an eye.

“If you messed up, you were punished for it,” he added. “That’s the long and the short of it and the better the opposition, nine times out of ten they punished you…they didn’t miss.”

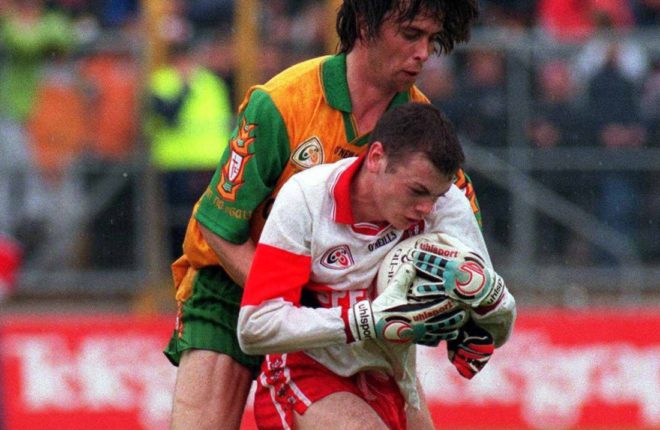

Derry overcame Armagh in the semi-final before struggling to get a grip on Donegal in a final that went down to the last play.

When Eoin McCloskey shanked a late kick-out, McFlynn beat his marker John Duffy to the breaking ball before somehow spooning it to Anthony Tohill.

“He just launched ‘er and Geoffrey got the turn and gave it to Brolly and that was it,” McFlynn said of the winning goal.

“I got Man of the Match in that final and that was a big confidence booster and I was only 20.”

VITAL…Man of the Match McFlynn wins Eoin McCloskey’s kick-out that led to Joe Brolly’s winning goal in the 1998 Ulster final

Derry were emphatically beaten in the All-Ireland semi-final, but a first ever championship point added to a performance McFlynn was happy with, one that gave the feeling he belonged at inter-county level.

A league title followed in 2000 with a replay win over Meath in Clones. In the championship, they nearly came unstuck against Antrim in Casement Park when two Kevin Brady goals had Derry rocking at Casement Park and it took Anthony Tohill to pluck a late Sheeny McQuillan free form above the crossbar to earn a replay.

“Close them windies,” manager Eamonn Coleman bellowed in the dressing room minutes later, before tearing the Derry players to pieces. Nobody was spared.

It was the same before training on the Tuesday night. Nobody was allowed out. Rather than starting to put a positive slant ahead of the replay, Coleman was even more animated after stewing on the game.

“It was one of those ones, you just kept your head down all the time because if you made eye contact he’d have remembered something else you did wrong,” McFlynn said.

Derry won the replay handy, but it cut the preparation for an up and coming Armagh team to just 12 days. Martin McElkennon did an excellent job of having them primed, but the game rested on a controversial late decision when Henry Downey’s textbook shoulder on Paddy McKeever was deemed a foul.

“Oisin McConville chipped it over and ran out past me, with his hands cupped around his ears as the Armagh fans’ air horns blared,” McFlynn recalls of a missed opportunity. “It’s one of those things I will always remember and I knew it was over at that point,”

Derry lost to Tyrone in the championship the following year before a run in the first season of the Qualifiers that saw them turn the tables on the Red Hands to set up another All-Ireland semi-final against Galway.

It was the story of one that got away, with everyone in Derry feeling it was their best chance of a second meeting with Sam Maguire.

“We were so ready and were five minutes up with ten minutes to go and it just fell to pot,” McFlynn states bluntly.

“I remember getting a free with 10 minutes to go and it was one of my biggest regrets. Instead of leaving it for Tohill to kick long, I kicked it short to Johnny Niblock and it was blown up for a short ball. It was hopped; they went up the field and got a point that left four in it.”

Matthew Clancy’s goal was the knife through the heart. There was another moment when McFlynn found himself on the ball in a crowded square without the space to shoot and electing to pass instead of fist it over the bar with Gary Fahy blocking down Gavin Diamond and Kieran Fitzgerald racing upfield.

“In the last ten minutes, there were something like 16 kick-outs and we won 10 or 11 of them,” McFlynn offers, with their game management not what it needed to be and shots peppered short into the arms of Galway ‘keeper Alan Keane.

He played on until the 2006 season when Derry beat All-Ireland champions Tyrone in the championship before losing out to Donegal in the semi-final.

A groin injury kept him out of a Qualifier win over Kildare but Derry were knocked out in a helter-skelter game away to bogey team Longford. It was McFlynn’s last season in Derry colours.

“I was having bother with hamstrings and lower back,” he said of making the call not to return for 2007. “There were always niggly injuries so I made the decision to just concentrate on the club. I wanted to try and win another club championship and give any injury free time to Loup.”

While they won two Ulster Minor titles in 1993 and 1995, they may well have won four in a row only for a narrow defeat to eventual winners Bellaghy in 1994 and missing crucial goal chances against Ballinderry’s Ulster winning team of 1996.

The production line Colum Rocks masterminded gave Loup an excellent starting point. Add in the 1994 Derry intermediate success and reaching the senior semi-final 12 months later under Martin Coyle.

“We came in and got straight to a semi-final and you think this is going to be easy and suddenly it’s not and you are fighting relegation for a few years,” McFlynn said of the five-year spell until Coyle’s brother Malachy came on board for the 2001 season.

A decent league campaign was followed by a disappointing championship exit at the hands of a Lavey team with the flickering hope of another title from their aging 1991 All-Ireland heroes.

“It was a devastating one and a case of men putting boys in their place,” McFlynn said, remembering Henry Downey’s address in the defeated dressing room. Loup needed to be pushing on, something that didn’t go down well with everyone in the losing camp.

“He was telling the truth, we were at the stage where we should’ve been beating Lavey,” McFlynn said of his former MacRory Cup manager and Derry teammate.

And push on they did. Patsy Forbes came in for 2002 on a one-year agreement. He brought fitness, passion and discipline to change the culture. Anyone who wanted to drink and party were allowed to do so, but they wouldn’t be part of the group.

Loup reached a first senior final in 66 years, but were beaten by Ballinderry as nerves and the occasion got to them against the reigning All-Ireland champions, with Sean Donnelly on board, who’d later marry his younger sister Karla.

It was still a year of progression with a league title; the club’s first senior silverware and a final win over Bellaghy, a first ever over the Tones at senior level.

“There wasn’t a massive celebration in the club afterwards, but it was important,” McFlynn outlines. “Marty (McElkennon – trainer) said not to underestimate the importance of this, it was a first senior cup and needed to be a springboard to something more…I can see him saying it yet.”

Outgoing manager Forbes had the same message. While the Loup players tried to talk him into staying, he kept to his word of one year in the midst of his busy life in business.

Loup searched “long, far and wide” for a manager that would take them to the next level. It wasn’t a time for stepping back and McElkennon recommended Malachy O’Rourke who had finished with Monaghan club Tyholland. Not only was he an excellent football manager, but a top class individual.

Paul was among a delegation of players who went with his father Bernard to meet O’Rourke in the Gables restaurant outside Dungannon.

“Who are your leaders?” Paul remembers Malachy asking. “He came in along with Leo McBride that March and the rest is history.”

The late appointment led to a slow burner at the start, but as the year went on O’Rourke’s ideas and McBride’s game-related coaching was sinking in.

“Video analysis and stats came into play. Everything was related to what happened on a Sunday and how they wanted us to play,” McFlynn explains of a manager he holds with the highest of esteem.

The Loup bandwagon was back on county final Sunday with Ballinderry again standing in their way. Looking back, Loup went into the 2002 final with hope. This time they were armed with belief.

“What I tell people about O’Rourke, it’s his ability to make you believe you can do it,” McFlynn said. “That has always been, to me, one of his strengths as a manager.”

With Loup leading 0-11 to 0-7, referee Adrian McGilligan waved away any Ballinderry appeals of a late penalty.

“Darren Crozier went down in the square, but told Bruno (McGilligan) on his way out he’d made the right call,” McFlynn said of those final seconds before the magical sound of the final whistle.

“I remember Shane McGuckin kicking it out and that was it. That immediate moment when you won it, you can hardly put it into words.

“Those first few minutes after the whistle, you were seeing people coming onto the pitch and grown men cry.”

It’s one of those moments when you want time to stand still. McFlynn made the decision to sip over two or three bottles of beer in the height of the celebrations. It was a more thronged social club than after their league triumph 12 months earlier, but he wanted to savour every moment.

“It was better than I thought,” he said of the winning feeling. “I remember watching Bellaghy, Dungiven, Lavey, Ballinderry and all the clubs winning, all the way back to Newbridge when Da was taking me to finals.”

In the realms of junior and intermediate football it was never a “realistic” thought, but it began to become a possibility.

KINGS OF ULSTER…Paul celebrates Loup’s win over St Gall’s in the 2003 Ulster Club final

“What about Ulster,” came a throwaway comment at the post-final meal in the Greenvale Hotel. It was McFlynn’s first inkling of anything outside winning the Derry title.

“Some celebrated to Tuesday and some celebrated to Wednesday,” he said of the after party before it crashed with a bang with a return to the training field.

As they filed out past the John McLaughlin Cup on the dressing room table, the Loup squad expected a gentle session.

It was one of the toughest sessions they did. There was running and running and more running. There was no exact science on show. Those who indulged too much were throwing up over the wire. When all was done, O’Rourke mentioned Ulster for the first time. The tone was set.

As it turned out, a 0-10 to 1-6 win over Bryansford was their toughest task, followed up by victory over 14-man Crossmaglen in the semi-final.

“If somebody had told us years ago that we’d be playing Crossmaglen in an Ulster Club semi-final and were thinking about beating them….we went into that game and O’Rourke had us believing,” McFlynn said.

“When you look at that team with the McEntees and Oisin McConville and all those boys, we never went into that game thinking we couldn’t win it.”

They followed it up with a win over St Gall’s in the final and Loup were Ulster champions. It was a long way from McFlynn carrying a white plastic bag to an u-13 game he got hammered in without hardly touching the ball. The years of toil were worth it

The loss of John O’Kane to a cruciate injury in a challenge game with Tyrone u-21s played havoc with their plans for an All-Ireland showdown with Caltra, a team backboned by the Meehan brothers.

Paddy McGuinness never gave Michael Meehan an inch from play, but his 1-5 from play shot Caltra to victory on their way to the title and leaving Loup pondering over what might have been.

Loup kicked themselves out of a Derry semi-final against Bellaghy the following season before losing to the Tones again in the 2005 decider.

“We beat Ballinderry in a semi-final that year,” McFlynn said. “They beat us on the league by 27 points and eight weeks later we beat them. That’s O’Rourke for you, but we played our final that day and Joe Diver put in a Man of the Match performance to beat us in the final.”

Ballinderry beat Loup again in the 2006 final. There was a huge motivation to win a second championship, but two more barren years passed before McFlynn decided to call time on his career ahead of the 2009 season. For now at least.

It was a chastening league campaign under new manager John Brennan and McFlynn was a spectator as Glenullin beat them in the first game of the championship of a season, sending them into the back door with relegation also looming.

Their oldest son Ger was born and time was tight, but deep down, he needed to lend a helping hand. Brennan had left the door open for a return at any time and there was grin on his face when McFlynn made an unannounced return to training.

The reserve championship was played over four Friday nights that summer with McFlynn in a centre forward role on the way to beating Bellaghy in the final.

The match sharpness helped him back in the groove. After championship wins over Kilrea and Castledawson, a convincing league defeat to Ballinderry led to Marty McElkennon’s return as coach, leaving Brennan more time to get inside the players’ heads.

The twin McVeys – Collie and Dominic – had the focus of limiting any frees conceded and their concession of just three points from play between them over the entire championship was another building block.

A win over Newbridge was followed by another meeting with Bellaghy with Loup coming through this time, for their first ever senior championship win over them.

Glenullin were tipped to come through on the other side, but it was Dungiven in the final as Loup set about getting their elusive second championship.

“Going into that final, we had a real fear of losing,” McFlynn admits. “It was massive; it would’ve meant we’d have won one final out of five, whereas two out of five sounds a lot better.”

In the build-up, John Brennan liked what he saw from Enda McQuillan in training. Injury and a jet-setting lifestyle curbed his involvement, but he was full of zest in McElkennon’s six on six possession grids.

“Brennan walked past me and said that wee man looks sharp; I think he could get you a goal,” McFlynn remembers of his manager’s comment before tipping his hat and walking on.

It was a masterstroke. In a game where both teams played with an element of fear and within themselves, it was substitute McQuillan who got a deft flick to touch Joe O’Kane’s pass to the net, ahead of advancing ‘keeper Peter McCaul for the winning goal.

With the John McLaughlin Cup booked for the winter in Loup, the squad went for food before the victory parade began down the Glenshane Pass.

“Brennan was sipping a pint of Guinness. He looked over and said “what about the wee man,” then winked at me and walked on,” McFlynn laughs about Brennan’s bold prediction coming true.

Wins over Derrygonnelly and Kilcoo had Loup back in another Ulster final. Once again it was St Gall’s who were on the march to an All-Ireland title with the same age profile Loup had against them 10 years later.

After leading by four points at the break, Lenny Harbinson’s side ran away with it in the second half.

“Too many of us were going the other way and they were at the right age,” McFlynn sums up of his last game for Loup. “We won the senior and reserve titles and we probably overachieved in getting to an Ulster final.”

He joined Liam Bradley’s Antrim management team for 2012, coming up one win away from promotion to Division Two and overturned Galway in the Qualifiers before deciding not to stay on for another season. A call to help managerless Creggan successfully beat relegation at the heel of 2012 led to two years as manager.

“Looking back now, I don’t know where I got the time to do it,” he said of his short management career.

“They say never say never, but at the minute I don’t see myself getting into senior or something so serious. I am helping out at Glen with the u-7s, that’s the height of it.”

The phone rang over the winter and while job offers can sound appealing, the realism of the time involved kicks in stronger.

He still lines out for Loup Thirds and it’s Glen’s underage teams that benefit from that calm and measured voice as they begin their journey.

For all the championship moments and intensity that defined Paul McFlynn’s career, it’s hard to beat a cool head.

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere