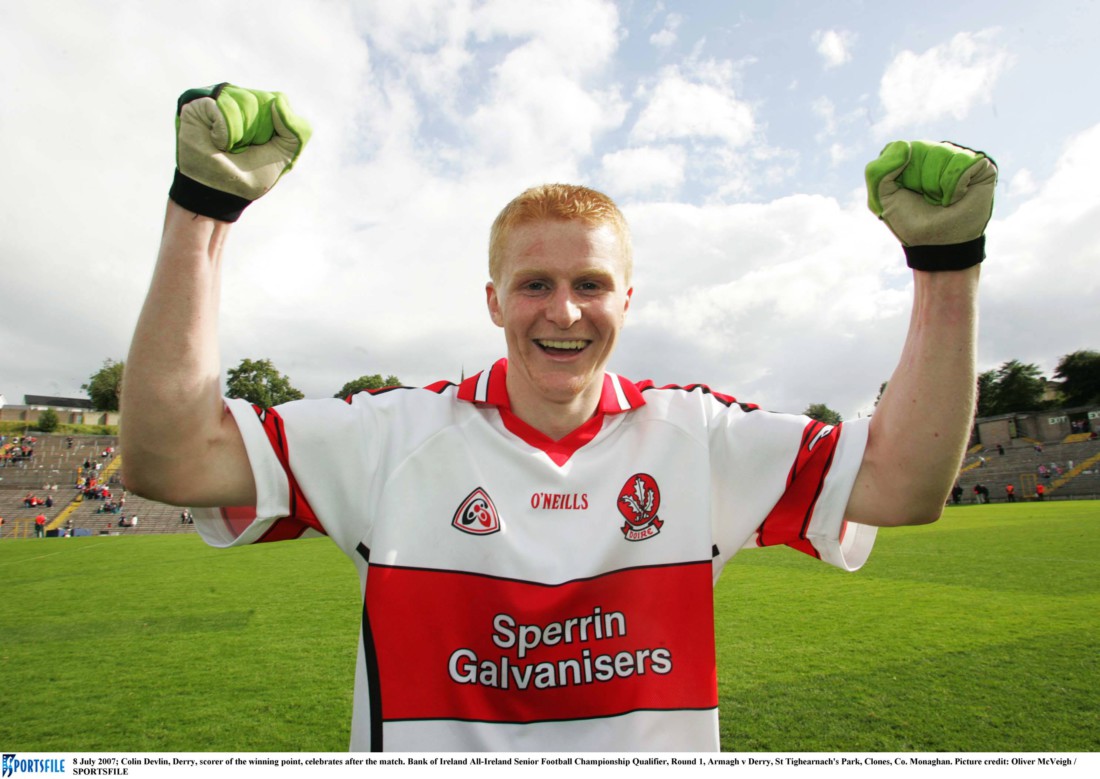

AFTER a career which spanned a decade, during which he played at the highest level for club and county, it may come as a surprise to find that Coílin Devlin said that he never enjoyed playing football.

“I am not one to use the word enjoyment when I am talking about football. It is a it scrooge-esque, but that is how I think.

“I think it is an overused phrase when people say ‘I am not enjoying my football’. I feel as if, largely, the people who come out with those statements are the people who don’t want to be there for the nitty gritty, or the hard graft.”

Devlin has experienced the hard graft. He played for his club Ballinderry since he was in primary school. He won regular underage titles throughout the ranks and would go on to win five senior county titles for the Shamrocks and an Ulster title in 2013. He played in a MacRory Cup final with St Mary’s, Magherafelt, and represented Ulster University at the Sigerson Cup. And he was a Derry player from minor through to senior before he hung up the county boots in 2013. Yet he explained why he thinks it is incorrect to describe football as pleasurable.

“Football is not enjoyable. Winning is enjoyable. The craic before training is enjoyable. The hard work during training is not enjoyable. The pressure that comes with competing in a county final, or a big final is not enjoyable, but you relish it in a different way. There is a challenge there and you have to step up to it. But you don’t step up to it with a big smile on your face. How many teams do you see coming out in a county final with the teeth shining at you and a grin from ear to ear? If you did see that then you’d think he was not wise.

“If you are hanging on in the 59th minute of a county final by a point, or being behind a point, that is not enjoyable.

“Look, there is a satisfaction when you achieve a goal. My addiction to football was competing, and trying to win. The enjoyment comes when you achieve that goal. There is a real weight off your shoulder. The journey is not an easy one. That is a big part of it. If you understand that then you know the commitment that is required.

“You’re not going out to enjoy yourself. You are going to do a job.”

For Devlin, the motivation to play county football was always the competition. He wanted to test himself against the very best. He did so for 10 years. He has plenty of medals at club level to prove his commitment, yet with Derry the prizes are few.

“Any of the years I played in Derry, we weren’t the best team in the country but we knew we had a great squad of players that could beat basically any other team, and we did. There wasn’t a team in Ireland that we didn’t beat. Consistency was our problem. There was a belief that we could win.

“There wasn’t ever a feeling that we couldn’t win the All-Ireland, if we would have been asked we would have said ‘aye’. But we tended to let ourselves down. We could be flat one day.

“Some of the years we were beat by teams and we were going in as favourites. That’s where the mental side kicks in and there is a wee lapse of concentration. There is a gap in a mental approach.

“It was a bit too up and down in those years, but we had the players to win things.”

The season that stands out for Devlin as an example of how Derry underachieved is 2006, when they beat the then All-Ireland champions Tyrone in the first round of Ulster.

“We went out the next day and got beat by Donegal. I was in rehab at that stage. After getting beat by Donegal we lost to Longford. They were teams we shouldn’t have being getting beat by. Then in 2007 we got beat by a Monaghan team that we should have been beating.

“In hindsight that was a Monaghan team that was starting to kick off. But we were a better team than Monaghan, then we went into the backdoor and beat Armagh who were strong. Then in 2008 we went out against Fermanagh. It was one of those not-all-there kind of performances. That was the year we had won the league, and confidence was high after 2007. We were just unable to put on the finishing touches. There just seemed to be a slight lapse of concentration on those days.

“It did feel there was a lot of quality in them teams, and real strong names through those teams. Sean Marty Lockhart, Johnny McBride, Paul McFlynn, Enda Muldoon, Paddy Bradley and a hell of a lot to go with that. The quality is there, but turning that into success isn’t easy.

“It felt that that generation underachieved.

“That team in 2008 had a great squad but they didn’t win much. Then those players retired and moved on. There is that period when there was a rebuild needed. but for the last 10 years the team has been trying to rebuild in a more difficult time to rebuild.”

Derry came awfully close during those years. In 2007 they went on a run through the backdoor that ended in an All-Ireland quarter-final appearance. In 2008 they beat Kerry in the National League final. Yet championship trophies were not forthcoming.

There are arguments to explain why Derry didn’t achieve in those years. Sometimes teams don’t win because there is a disconnect between the squad.

Devlin said: “It didn’t feel like that at all. Everyone got on.”

The other argument is that club football took precedence.

Devlin said: “It’s hard to judge that. Everyone is different. I find it difficult for someone to say that they love their county more than their club. I’d be disappointed if the vast majority of people said they love their county more than club. That doesn’t mean that you have ill feeling for your county. Club is something different. That is where it all starts. Your county is different. You don’t start going near your county till you are 15 or 16, or at least that is what it was in our day. Suggesting that club was the problem is just a way for someone trying to find a reason for a lack of success.

“But if you go up to play for the county then you have to be committed.”

For teams to make the difference, and players to make the difference, they have to be motivated.

Devlin believes that he was motivated when he was a player.

“You have to live like a professional and your sole motivation should be to win. When you go to training or go to matches you have to have that drive in your stomach to want to win and to be the best.

“But it is more difficult to commit yourself nowadays than 10, 15, 20 years ago.

“Our level of commitment didn’t need to be back then what it is nowadays because of how professional football was. My level of commitment was 100 percent all the time. But 100 percent in my day was training Tuesday night, training Thursday night and a match at the weekend.”

Devlin said that nowadays players are expected to train almost every day. He noticed the change in attitudes in 2013 when he returned after a four-year break due to injury.

“I remember being told that we had to be in Owenbeg nearly five days a week. That was behind what other counties were doing. But that was more than I was used to. How do you get guys to buy into that if they are 15th in country?

“Coming back in 2013, not to confuse the training, it was mentally intense. It put far too much strain on me and I told Brian (McIver) that I couldn’t do it again. That was me at 28 years of age. I had a full-time job that dictates a large part of my time and mental capacity. There was nothing different about the type of training or tactics or approach. It wasn’t a physical thing, it was a mental thing. It was having to be there so much.

“It was ingrained in me that it was Tuesday, Thursday, Sunday. To then change and get a change that is a shock to the system.

“The change in attitude towards training came in around 2010 and it has grown and grown. The only way for teams to keep up is to increase. Some teams are able to keep up, and some players are likely to give that commitment. If you feel close to your goal then you are likely to give that commitment. But if you feel like you are miles away then it is harder to give that commitment.”

Devlin believes that the issue of commitment expectations from players must be addressed. However, he also thinks that expectations from managers and fans also needs looked at.

“I think teams have to start the year and have realistic goals. Not everyone is going out to win the Sam Maguire. But they have to have goals that are X, Y and Z, and they judge their season on whether they achieve their goals. Not who beat them in the championship, or what round you went out in, or how much you were beat by. To me it has to be baby steps. Once players start to see themselves achieving goals, then they can raise the bar. I am sure that is what is happening, but at the end of the year you only hear teams being judged on championship, it is always been that way. But if you judge yourself on championship then 31 teams will go away depressed.

“There are more teams in this boat. My view is that there should be a system that makes it possible for teams to compete and to feel a purpose and for the ability to be successful.”

Devlin said that there are some people who are playing football to be seen to be playing for the county, or for the prestige.

“That’s no good. If you are doing that then you are not there for any intent. If you are there just to be there then you are doing the team a disservice. You are not giving anything back to it. If you are content to be part of it, then you are not driving to be on the team. That commitment and that drive to be on the team will drive everyone else on. That builds a stronger unit.”

Commitment to playing football was something that Devlin believes is a strong part of his character. However, he isn’t sure why he is so determined to compete.

“That’s just the way that I am. If I can’t be fully committed then I don’t get involved. I wouldn’t start on a journey if I know I can’t complete it. I could easily have went back to the panel in 2014 and been part of it, but I said at the time that I had to step away because I couldn’t commit.”

That strict rule of commitment would cost him though. At the end of 2010, John Brennan got in contact with Devlin. Brennan, who had a remarkably successful club management career, winning championships with multiple clubs, took over the Derry job. He wanted Devlin to get involved. Devlin told him that he couldn’t commit because he was still recovering from injury and he wanted to get a year of club football before he tried to go back to the county. Then the Ballinderry player watched as Brennan’s Derry enjoyed a great run in the league and reached the Ulster Championship final where they were beaten by Donegal.

“I was sitting watching thinking that I maybe should have got involved. Derry were playing good stuff, and were unfortunate that ‘Skinner’ (Eoin Bradley) and Paddy were injured. Had they won that game I would have felt that I should have got involved. But that would have been selfish.

“I could have said yes and played that year and not been fully fit. There are many things in life that I am asked to get involved with but I won’t do so unless I can fully commit. All you are doing is filling a slot where someone else could come in and do a better job. That mindset feels natural to me.”

Devlin’s perception of commitment, and dedication to the team was perhaps born in his formative years as a club player with Ballinderry, where the teams were strong and he understood that to be part of that success he had to work hard.

“It wasn’t easy getting on to teams. I was fortunate to grow up in a golden generation of Ballinderry. We had great underage teams but we never won anything easy. We did win championships but nothing was gifted to us. We had great teams competing with us.”

But it was playing for his school, St Mary’s, Magherafelt, and also for his county, where Devlin learned how important commitment was for those who want to succeed.

“When I was underage with Ballinderry I expected to start, but it was different moving into schools football. You are judged just the same as the rest. You are not judged as someone who has been there since they were six or seven years of age. That raises a bit of competition. You have to prove yourself. If you go into school or into county on the first day you have to prove yourself.

“The biggest challenge I had was that I was small. You had to be of a certain size or build to be seen at schools football or to cope. Schools football lent itself to bigger players whether they were good at football or not. My biggest hurdle was that I was tiny. It wasn’t until I got to 17 that I got a growth spurt.”

When he was fourth year at St Mary’s, the school won the Rannafast Cup title. Yet it wasn’t a year that Devlin celebrated.

“I felt that I should have been picked for that team, but I wasn’t picked. I was tiny in comparison to the rest, but I knew my ability and what I could do. That was the first year that I didn’t start. From that point I had to prove myself. I dropped down a peg. I had to work harder to make sure that I was picked. I had to work with what I had got. I knew what I was good at.”

The challenge of winning his place at school was the same at Derry.

“You had to work hard and you had to perform to get the chance at underage and senior level. Maybe being forced to compete helps you. But it was a trait of mine to want to compete and want to be successful.

“You had to work harder so that coaches could see the other traits, your pace or your scoring. There are so many different components to a player. If you got it easy all the time then you might be less capable of competing when the challenge did come. Those who get things handy, then it doesn’t stand to you.”

What is perhaps interesting to note is that size was a hurdle that a lot of his Ballinderry teammates had to get over, so to speak.

“The Ballinderry teams we had at underage were never big. I can mind going to Féile and me and James Bateson playing midfield. Both of us were small. It was crazy, but at that level pace and skill got you by and more.”

At schools level, The teams he played on weren’t massively successful. The school won the Rannafast. Devlin remembers robbing Maghera in the final with two late goals.

The next success was their run in his last year, when they reached the MacRory final in 2003. While they lost to Maghera, lessons were learned. And not just by Devlin.

“That was one of the years that the six previous years all clicked in one year. It wasn’t a business-like group of players like the Maghera team I imagine was like. There is a different emphasis put on football in Maghera than there was in the Convent (St Mary’s, Magherfelt). We enjoyed the craic and things clicked and we beat the best teams in it. Our strength was the group we had.”

There weren’t many players who went on to play county football. The captain was Ruairi Murray. Michael McIver did play for the county. Ciaran McCallion was midfield, and there was Joe O’Kane from the Loup.

“It was enjoyable year, and we probably should have did better. But I didn’t really take schools football as seriously as I took Ballinderry. I maybe didn’t take it as serious as boys who were coming from weaker clubs who weren’t as successful. But that year was positive. The school rallied around that. In hindsight you realised the lift that it gave the school. I think that run made a difference. At the time football wasn’t a priority in the Convent. They facilitated a football team. It wasn’t a priority to commit. I think that that year opened a lot of eyes in the school. They got a buzz from the team going on a run, and they realised there was mileage in applying a bit of focus and attention on football.

“Things changed after that. There was more time and effort put into the football set up. Maybe it helped a bit towards the lads winning the MacRory a few years back. They maybe were starting to take notice.”

After St Mary’s he went on to play Sigerson Cup football with Ulster University. Devlin won the Freshers in his first year. The Freshers football was ‘not a priority’ for Devlin, but he liked playing at that level and playing with new footballers, and competing in a new set up.

What he learned was how to play a different style of rugged football that is usually played in the winter. He also experienced playing a higher standard of footballer.

“In 2005 and 2006 both years we let Queen’s beat us at the death. We should have had them dead and buried both times. I think about those games and wonder how we lost them. I have won a few of those games like that. It’s great when you win them but awful when you lose them.”

He missed the 2007 season, when he was injured. Yet his conclusion was that Sigerson football was a positive experience and for a player who wanted to compete it was perfect for him. But in those years after school, it was club and county that were his priorities.

He isn’t sure if it is the reason, but he got injured in 2006, after a period when he had been playing at the highest level at club, schools, colleges and inter-county. Injuries would, unfortunately for Devlin, become an unwelcome part of his life.

“It was at that time when I started to pick up injuries. That (the heavy schedule) might have been the reason, but who knows. Mentally I was happy to be playing at that point.”

Injuries and how he dealt with them provide us with an interesting insight into Devlin as the player. The first injury happened in 2006 and from that point onwards, he always struggled to stay fit.

“In the early days, it was easier to deal with injury. When you are young you feel that you have many years ahead of you.”

But as the years wore on, more things started happening, and he struggled to get a proper season under his belt. He would pick up the injury, rehab, battle back, and go again. Commitment to getting back to being competitive was what drove him on. However, he soon learned that dealing with injury isn’t merely about managing pain and recovery.

“One of the biggest difficulties with being injured is the shit you have to deal with for being injured. Anyone who is injured doesn’t want to be injured. But you have to deal with people who say you don’t want to play. That mindset seeps through to managers and other players, and it can affect you as well. You become ‘the player that doesn’t want to commit, who doesn’t want to play’. So if you are that person why would the manager want to pick you?

“You have to have self discipline to deal with that. It’s very difficult working on your own. You could say I’m injured I’ll sit out for a while and I will be grand, but you are only kidding yourself you have a lot of work to do to get that part of your body right, and then the rest of your body back to the same level is difficult. It’s difficult to do it once, but to have to do it in a cyclical fashion it is mentally draining. The one part of it that you want to be involved in is the match on Sunday. But that’s the part you sacrifice when you are injured. It is not logical to think that you would be bluffing to get out of a match. To train all week and then not be able to play on the Sunday, that’s hard.”

For someone who prided himself on being committed, who played for the competition, who wanted the satisfaction of working hard towards a common goal, that would be frustrating.

“I think modern day players tend to want the praise and adulation. I think they would find it harder if they were taking that sort of shit. But there are players who have the old school approach that they nearly need the challenge. I was the sort who wanted to prove people wrong. If people said bad things about me I used it as a motivation. It helps to be that way because criticism is unavoidable the higher the level you play at.”

The opportunities for criticism were many unfortunately for Devlin. The injury cycle that he suffered through is almost heart-breaking.

“I was involved with the county for a long time, but most of the times I was injured. The injuries kicked in early. I was up there in 2005, then got injured with the u-21s in 2006. I mind pulling a muscle in my quad during a kick passing drill. It was a small thing but it ended up being a big thing because it never went away. I struggled in 2006 with the quad. By the end of 2006 I was only able to play a bit part in the club.

“Then when you get your head above water, then we went out in Ulster and in the first game I got a clash in training and I tore the medial ligament in my knee. Then I was on the merry go round for injuries. In 2008 in the semi-final I had a clash with Geoffrey (McGonagle) and wrecked my ankle. I struggled with that. Then Crossmaglen beat us in the final. Then I did pre-season for Derry, then I did rehab and realised it was a futile exercise.

“Then in 2009 I wrecked the other ankle. It was 2010 that I came back to football with the club. I played four games. Then in 2011 the quad put me out of the championship. I came on in sub appearances in Ulster. 2013 was one of the best years I played with Ballinderry but I suffered all year with sciatica in my knee. Every game I took pain killers. It was a struggle. It wasn’t a bit of wonder that it took its toll. After 16 that was me.”

The later years were not easy. In 2014, Ballinderry were at the centre of a controversy in Derry when, after a row in the county final between them and Sleacht Néill they were faced with a series of suspensions, including Devlin himself. At the end of 2014, the county board suspended Aaron Devlin, Michael Conlon and Gareth McKinless for a year.

Then tragedy struck the following year when Aaron, Coílin’s brother, died from meningitis.

“I don’t think the team ever really recovered from that. I don’t want to pin it on that. But everything that happened from 2014 right through, it affected that team massively. It rocked the team and the club. It has been a difficult time since then.

“That was a massive upheaval. There was a widespread effect on everyone. Club teams are close. You are playing with friends and family. That affected everyone and was a lot for us to deal with. It wasn’t long after that we had to compete in championship football. It was no surprise that we lost.

“In 2015 I was going out to make up for what happened in 2014. In 2016 I was going out to make up for what happened Aaron in 2015. You use stuff to motivate you. But I got injured and it was a difficult year. There was a fall out between me and the manager and then Sleacht Neill beat us.

“I pulled the pin after that. I went out quietly which isn’t the fashion now. I didn’t put an emotional post on Twitter (laughs) or anything. Almost immediately I was done with it. I had put so much effort in for so long and then I was done with it. Maybe it was a culmination of a lot of things. Injuries, work.

“It felt like the right thing to do.”

The management convinced Devlin to stay on and he played reserve football that year. He was able to enjoy it, and not have to go through the intensity of first team football. But injury hit him within three weeks. That was the message that he needed to remind him that GAA was over.

He stuck around until they won the reserve championship, but when that competition was over, he was sure that he wasn’t going to play Gaelic football again.

He knew that he couldn’t give it the commitment it needed.

If we take Devlin’s philosophical approach to football, at its centre is the issue of commitment, and being dedicated to achieve a goal with a group of players. Yet it could be argued it was easy for him. He was born in Ballinderry, during a time when the club were swarmed with great footballers. He went to a school in south Derry that had a solid group of footballers. And he played for a county team that was also blessed with some fine proponents of the game. Perhaps it was easier for him to commit knowing that he had a better chance of success than others.

“I was fortunate that the success in Ballinderry happened when I was playing. I do have that appreciation when I am talking to players from the other end of the spectrum. I can relate now. Both club and county are now in a different period than when I was playing. Absolutely I was fortunate. Hugely fortunate.

“Ballinderry is not a big place, but to have that group of player was, I don’t know if I want to use that phrase, golden generation, but we were fortunate. Ballinderry churned out players for years, we were fortunate to be in the middle of that.”

You could argue that Devlin saw that there was potential to compete at a high level and he got involved. He says that playing football was partly about going along with mates and competing.

“If I was growing up and all the teams that I was involved with were not at a level of competing, would I have got involved with the same commitment? I don’t know. I can understand why players find it hard to fully commit to a cause. It is much easier to commit to a cause that is going to produce the goods. I was fortunate to be involved in teams where that was the case.”

Yet there is the feeling that Devlin probably would have got involved even if the probability of success was low. The evidence is there in his post-GAA pursuits.

After his GAA career was deemed over due to injury, Devlin sought out new challenges. Golf was one pursuit he enjoyed, but it took a sideline to another sport, a team sport to be exact.

“I joined Magherafelt Sky Blues (soccer). Raymond Wilkinson was playing with them and he said I should come out. I said to him, ‘is it that easy? Do you just show up?’

“That suited me as it didn’t demand the same level of commitment as the Gaelic. But there was a level of competition. It was going good for a few weeks, but after a couple of games they asked me to play for the firsts. The firsts were competing for the league title. I didn’t want to get involved I didn’t want that extra pressure. But I did and I was glad I did because I played in the next two or three games, but then I tore my Achilles. That’s the worst. Of all the injuries I had in my career this was the worst one, the king ding. And it came at the very end.”

So team sports ended for him at that point.

Yet life for Devlin cannot ever be about sitting on his sofa thinking about the glory days. Last year, he discovered a new sport, namely the Spartan run which is a mix between a cross country or mud run and an obstacle course.

“You have to keep trying to find something. With football it was easy, you joined up and everything was set out for you. Training was set, and the match was set. Now you have to be searching for something new. With the Spartan race it will give me a bit of fitness, and a bit of competition.

“I need it to be a group orientated thing. Motivation is difficult. Fair play to those who can do things individually. To me that is tougher than a team sport. When you have a team you motivate each other. The team or the group aspect is massive. To find something like that is important.”

As long as he has something that he can commit to and be competitive, then Devlin is happy, but don’t ask him if he enjoys it.

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere