It’s 20 years since Loup were crowned Ulster Club champions. Fintan Martin kicked three points off Francie Bellew in their semi-final win over Crossmaglen and he spoke with Michael McMullan about a memorable year.

SPORTING stories are like journeys. There’s the start that leads into the meandering chunk in the middle, followed by the destination.

It takes all three for completeness. That’s why it’s impossible to start Loup’s tale of silverware on the steps of the Gerry Arthurs Stand in Clones without going back to where it all began.

Ask anyone in Derry underage football circles across the eighties and nineties and they’ll tell you about Colum Rocks, a man at the crux of Loup youth teams.

‘Super’, as he was affectionately known, poured his soul into it. A fanatic. Would Loup have reached the pinnacle of Ulster club football without him?

If so, they’d have needed to have been cut from the same cloth. Whatever time Colum Rocks didn’t devote to the other fs in his life – faith, family and friends – was ploughed into a project that would change Loup forever.

Bogged down in junior football, a meeting was called in 1986. Things needed to change. Arrangements were made for Dublin duo John O’Leary and Noel McCaffrey to visit Loup.

Word spread that Loup pitch was the place for any youngster who wanted to play football.

That was the start of a plan that would first deliver an u-12 B league the following season. They’d lose the championship semi-final to Ballinderry, but Rocks had his foot on the throttle.

The Loup underage conveyor belt had begun. The group of players Rocks said were “always his number one” hoovered two titles at every grade on the way up through, u-14, u-16 and minor level, culminating in two Ulster minor titles in St Paul’s.

Fintan Martin was part of their memorable journey through underage. With the mention of Colum Rocks, you can hear the emotion hanging on every word of his voice coming down the phone.

“He wasn’t a coach or a trainer…he was a father figure,” Martin said with the type of sincerity his words can’t fully deliver.

“I still constantly go to his grave and I’d always have a chat with him.”

There was a full turnout at a reunion of the 1993 minor squad before Rocks sadly passed away the autumn of 2018. Nobody missed. They loved him. Worshipped him almost.

When Rocks would bump into his former protégées in later life, he’d always be asking about life, about work and about family.

“It wasn’t just football…he just cared,” Martin explains.

What about his daughter Aoibheann? How was his son Dara Joe getting on?

“That’s it in a nutshell. He just cared for absolutely everybody…every player,” Martin added.

Silverware was half the legacy. The other half, five scrapbooks in which he kept every nugget of press coverage from nearly a decade of their progression.

His nephew Ronan has them now. They’re annotated with season summaries and squad lists in Colum’s own handwriting. Money couldn’t buy the stories they tell. He worshipped the players he moulded.

“He was ahead of his time in terms of nurturing players, he was something else. An absolute legend,” Martin concluded.

“He had something special but he had a special group of players too.

SUPER IMPACT…Colum Rocks (second from left) was the driving force at underage level with the players who would win Derry and Ulster senior titles

“You often hear of a bunch of players coming through at one time, we were damn lucky.”

Loup’s bunch of cubs flooded a senior team who were promoted after winning the 1994 Intermediate League and Championship double.

The only regret was that Colum’s imprint at senior level was limited to one single year as part of a management team that were gone after one season and an early championship exit.

Like the other years since Loup’s promotion to senior until they were crowned Kings of Ulster, the management was often the scapegoat.

Games they were expected to win were lost. The management team was moved on, and so the cycle continued.

***

For his years of spadework, Colum Rocks deserved much more.

If underage was part one of Loup’s journey to the top of the tree in Ulster, promotion from intermediate was the second step.

Then, after a stagnant spell, the 2002 season was the crossroads. Loup were spluttering along and needed to look themselves in the mirror.

“We were our own worst enemy from 1995,” Martin admits. “In our first year up in senior, we got to the semi-final against Ballinderry.

“They scored a flukey goal, wee Bambo (Paul Conway) toe poked it into the net over in Ballinascreen.”

Martin sums up the next six years with total honesty. He doesn’t sugarcoat it. They did nothing. Absolutely nothing.

It was a year-on-year blame game where the players were always spared with an excuse conjured from elsewhere.

The talent was hanging out of them, but it wasn’t enough to regularly cut it against the big boys.

“We had only ourselves to blame,” Martin admits with the benefit of hindsight and seeing the shoes they would later walk in on the way to Derry and Ulster senior titles.

“We blamed the managers that were in there. We blamed this and that, boys heading away but it was our own attitude that was stinking.

“We thought we would’ve walked through senior football like we did at intermediate and it didn’t happen.”

Martin uses the example of their Intermediate Final win over Desertmartin.

He was part of a teenage front three – with Gary Coleman and Enda McQuillan – that burled 0-10 from play.

“We automatically thought we’d do the same in senior football,” Martin said.

Being young, fast and two-footed was only half the battle. Coming up against seasoned defenders was a different ball game entirely.

The arrival of Patsy Forbes as senior manager at the start of the 2002 season was timely. The perfect fit.

A team of young bucks, needing a “kick up the ass” met Forbes, a driven winner in everything he put his mind to.

“He put a bit of sense into us, discipline both on and off the field. We thought we were above ourselves, but Patsy grounded us,” Martin said.

He was a fitness enthusiast and would join in for the training runs. If he could last the pace at his age, then the players had no excuse was the unspoken message.

Drink bans weren’t imposed but Sunday morning training sessions separated those who wanted to fully invest in football from those who didn’t.

Martin remembers how Forbes, still an All-Ireland runner in his mid-sixties, was hands-on with training.

When players were kicking in and out before the session began, he’d often come with a “reever” of a shoulder charge. If you didn’t spill the ball, great. If you ended up on the ground, you had to get back up again.

“If we were playing a match in training and were a man down, Patsy wouldn’t be long handing the whistle to somebody and he’d pick up the spare man,” Martin said, before recalling a scene from an in-house game.

“My brother Roidan was coming in to pick up a ball. When he saw Patsy steaming in, he stepped back and Patsy hit into a concrete post.

“He jumped back up and wanted to play on, saying there was nothing wrong with him even though the blood was gushing out of the back of his ear.”

That type of enthusiasm and singlemindedness rubbed off on a group needing growing standards to gauge themselves by.

It was a regime that got Loup all the way to a first county final in 66 years.

“Unfortunately, the occasion got to us more than anything, we didn’t turn up against Ballinderry in the final.

“Once Malachy (O’Rourke) came on board in ’03, it was a no brainer that we’d be back in the final again.”

Forbes told Loup he was committing to only 2002. Just one year. Before he signed off, the rubble of the county final defeat was picked through ahead of the league play-offs.

Wins over Sleacht Néill and Bellaghy delivered the club’s first piece of senior silverware. Small, yet massive. All in the same sentence.

“I wouldn’t belittle the league,” Martin said. “It’s not that it didn’t mean anything to us because it was the first senior trophy that came to the Loup.”

The Intermediate Championship and League titles won in 1994 were a start but with Bellaghy flying at that stage it gave Loup another handle to hang on to as they looked into the winter of 2003.

***

Malachy O’Rourke had cut his teeth by talking Monaghan club Tyholland to success.

Loup didn’t just want anybody to fill the management post. It needed to be someone to finish what Forbes had started.

Internally, they kept training, tipping away to almost the shoulder of the league season until they got their man.

A delegation met O’Rourke in the Gables restaurant outside Dungannon to sound each other out. Days later, the white smoke was bellowing. O’Rourke and his wing man Leo ‘Dropsy’ McBride were on board.

Loup’s league form was far from inspiring and they were looking up the table rather than down it.

In an interview for the upcoming book Derry: Game of my Life, Paul McFlynn pointed to a win over Ballinascreen and the manner of the performance as the start of a change in fortunes.

Martin also uses the word momentum when feeling around for the moment when Loup’s magical 2003 season began to grow legs.

He points to the first round of the championship against Lavey, but not before pressing the rewind button to a few years previous when Lavey dished them out a lesson.

“They tanked us in the championship down in Bellaghy,” Martin remembers.

MAN WITH A PLAN…Malachy O’Rourke steered Loup to Derry and Ulster titles in 2003

It was Fermanagh defender Paddy McGuinness’ first season since his transfer to Loup, but Paul Hearty dragged him all over the place.

Martin described the defeat and performance as embarrassing. As was fully in vogue at the time, the winning camp would say a word or two in the losers’ dressing room.

Henry Downey told the Loup players they needed to take a hard look at themselves.

“He told us they were an aging team and they just put us to the sword,” Martin remembers.

They didn’t want to hear it, but they never forgot it and Malachy O’Rourke’s forensic research didn’t take long to lock in on it as a twig to light a fire with.

All through the 2003 season, the word Lavey was drip-fed into Loup’s psyche without them even knowing.

In the week of the rematch, O’Rourke stoked the fire with references to “disgrace” and being beaten by “a pile of old men”. It was time to reverse the result.

“They were no bad team but we annihilated them,” Martin said. “It all came from O’Rourke doing that bit of digging and it was a big turning point in our championship.”

Wins over Kilrea and Glen followed as Loup got themselves back to the final championship Sunday and another crack at Ballinderry.

O’Rourke’s work was only beginning.

***

Win or learn. Loup definitely plucked the latter from their 2002 defeat to Ballinderry.

The Shamrocks were reigning All-Ireland champions, whereas Loup were the new kids on the block. They never stood a chance. The occasion swallowed them up.

A first final in 66 years. Flags. Bunting. New jerseys. Talk of supporters’ busses.

“We never turned up…we never got a score from play that day,” Martin bluntly said of their 2002 final failure.

“Big (Ronan) Rocks scored six frees and that’s all we got. We were horrendous across the board.”

O’Rourke’s work was simple and effective. He had told the Loup players that if they got him to the semi-final, he’d get them over the line. Get them back to the final and he’d find a way of getting their hands on the John McLaughlin Cup.

It was the same in Ulster. It was a two-way bargain. The players would keep their end and the management would meet them half way.

How did O’Rourke get a team failing to score from play in a county final into a championship winning unit that almost ran out at Croke Park on All-Ireland final day?

A complicated tactical masterplan? A total change in training? No. There were tweaks, yes, but Martin puts it down to targets.

O’Rourke assigned the defence their marking roles and told them how they’d individually succeed. If someone bombed forward, they’d be covered by a dropping player.

There would be a two-man full-forward line, with Paul McFlynn popping up wherever the ball needed caressed and sent on.

Then it was a game of ownership and targets. Martin, a scoring corner forward all the way though underage, was told he needed to chip in with scores.

His runs needed to bring him to the right places. If it didn’t yield scores, then assists would do as a fall-back plan.

“If you don’t get two or three, then let’s create four,” O’Rourke would tell him.

Shane McFlynn would’ve been on the edge of the square. It was the same line of questioning. If he wasn’t grabbing a goal and a couple of points, was he really doing his job?

“Paddy Finn (Paul McFlynn) was roving out. Enda McQuillan needed to get scores,” Martin continued, with the level of recollection as if he’d just stepped out of a random 2003 team meeting.

“Everybody was given their own roles and it was the same defensively.”

There was a limit to the amount of scoring frees that could be conceded. Teenage full-back Joe O’Kane was told his man wasn’t allow to score a goal. His brother Padraig at centre back was given a limit of how much he could concede from play.

When Fionntan Devlin picked up Oisin McConville in the Ulster win over Crossmaglen later that autumn, he had his targets.

Loup’s corner backs were convinced they’d be able to lock down a Conleith Gilligan or a Gerard Cassidy as county final day approached.

“O’Rourke would sit back and watch training, taking notes,” Martin said. “There was no whiteboard coming out with a pile of arrows.”

There was plenty in the preparation, but it was kept simple and players knew their end of the bargain.

Any defender who coughed up their match limit of two conceded frees by half time would be told to tidy up their tackling or there would be a change.

At one point in the campaign, Martin remembers sheets of paper being circulated to the panel. It had the players’ stats. How much they’d scored and how it sat as a percentage. All the key markers were on it. It was about mind games and ownership.

“I am not sure if he was making us compete with each other,” Martin still wonders, “but he’d always ask you to climb the table to get your percentages up.”

***

To take on Ballinderry, Loup had to fully look at their mental preparation. Why did the 2002 county final day chew them up and spit them out.

“There is nobody who could’ve stood up and said they gave their all, the game passed everybody by,” Martin offers.

“In ’03, we knew that couldn’t happen again. We stepped aside from the circus, everything with regards to supporters, the flags and the bunting.”

There were two buzz words – low key. The Loup players weren’t told to ignore those at home, but they needed to put a cap on the level of football conversation.

They were told to pass themselves and let the fans worry about the build-up, to keep their heads down until the next session – stay away from the circus.

When they stepped off the bus in Celtic Park, they’d fish their bag out of the boot. If listening to music was their vice, fair enough. They just had to look straight ahead and trot all the way to the dressing room.

“My father-in-law, big Spud (Brian O’Neill), was standing at the back of the changing rooms at Celtic Park and I didn’t even notice him,” Martin laughs.

“The next day he said to me about be ignoring him but I didn’t see him standing there at the gate. We were in the zone at that time.”

Another aspect of county final day – when is it time to rev up? Do you need to get more up for a derby with Ballinderry? After a limp 2002 decider, did they have to take the dressing room door off the hinges on the way out?

“We needed to keep it amber…the amber light until you have to switch it to green,” Martin said of Malachy O’Rourke’s traffic light philosophy on getting primed for battle.

Getting too worked up wasn’t the answer. Energy needed saved not wasted in dressing room tension that can suck then life out of legs that have spent months getting tuned.

“Keep ‘er amber,” O’Rourke would tell them. A calm dressing room, warmup and calmly marching behind the band. They’d push the button the time was right.

“In the last huddle, he’d tell us to flick the switch and that was us ready to go with no nerves,” Martin said.

It was time to go green and when Paul McFlynn kicked the first point, with his left foot, the ghosts of 2002 were banished.

Loup had scored from play early doors and were here for one thing – the club’s first senior title in 67 years.

Ask Fintan Martin what sticks out from the 2003 campaign. Without mentioning the fact he kicked three points off Francie Bellew, he picks the win over Crossmaglen as the moment.

“Between the Crossmaglen game and the county final against Ballinderry, they were two steps more than anybody thought we could do,” he said.

***

Crossmaglen. For almost two decades, their name alone left many teams a point or two down before the ball was even thrown in.

By the time Loup played them in the 2003 Ulster semi-final, Cross had added three Ulster and All-Ireland titles to their 32 Armagh Championship wins.

“I still go back to the Crossmaglen game because we were given absolutely no hope outside of ourselves,” Martin said of his standout moment.

In a heartbeat, he recites the core of their team. The McEntees. John Donaldson. Francie Bellew. Oisin McConville.

“We were written off, given no hope,” Martin said. “That game stands out more than the (Ulster) final because once we got there, we felt we were going to win it.”

Outside the Loup squad, they’d no chance. A couple of miles down the road to Ballyronan village, across into Ballinderry, Newbridge and Magherafelt.

“Inside our circle, we all had the belief but once you went outside that…the feeling was that after winning the county (title) it was as far as we were going.”

Newspapers were bigging up Crossmaglen. Especially after Loup needed a late Shane McFlynn point to see off Bryansford in a quarter-final they had a grip of for long spells.

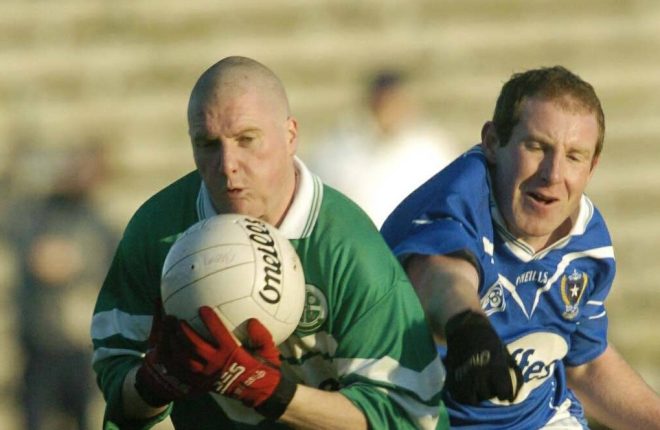

ON THE BALL…Fintan Martin the Loup forwards were urged up their scoring rate under Malachy O’Rourke

“People thought the party was over after scraping through against an average enough Bryansford team,” Martin said.

Beating Crossmaglen gave them a chance to pump out their chests to the doubters.

“It is like any team when they are underdogs, written off by media and neighbouring clubs, it only adds fuel to the fire,” Martin added.

John McEntee’s 13th minute sending off gave Loup a helping hand. Another was holding Crossmaglen scoreless from play for the duration of the second half, tapping into the metrics O’Rourke had them measuring themselves off.

Martin had three points to his name. Skipper Johnny McBride, Paul McFlynn and Ronan Rocks landed two apiece.

Stripping that all back, Martin spoke of their belief. Across challenge games, an Ulster minor championship game in St Paul’s and an Ulster Óg Sport in Crossmaglen, Loup were unbeaten against them.

“You couldn’t say we took absolute belief from beating them in the minors, we didn’t fear them. We didn’t fear anybody and definitely didn’t fear Crossmaglen,” Martin said.

“They were next in line and it didn’t matter who it was, Cross, Four Masters or St Gall’s, we just had to go in with no fear and O’Rourke was the master at belief.

“That’s what he instilled in us, pure belief. As a collective, he was good at that.

“Individually, he did the same to every single player and that was what was brilliant at. He’s a legend and there should be a statue put in the Loup for him, there is no doubt about it.”

O’Rourke’s planning even went as far as advising the team how to celebrate and carry themselves at homecomings.

For the Ulster games with Crossmaglen and St Gall’s, Loup stopped off at St Patrick’s Donagh, across the border in Fermanagh.

It was close enough to stay zoned in until arriving in Clones, yet far enough away to keep themselves away from the green and white frenzy.

After beating St Gall’s in the final, the Loup bus pulled into Donagh club for a bite to beat and a few pints in their own company before taking the Seamus McFerran Cup back home.

“Even after beating Ballinderry, O’Rourke would have told us not to be putting a feed of drink in us,” Martin said.

Youngsters looking for photos and autographs needed to be shown good example. Older fans, who’d followed Loup through thick and thin, would be coming up to shake hands.

“When we got back to the Loup crossroads, a piper came and walked us into the pitch with the fireworks going off,” Martin said of their Ulster homecoming.

“O’Rourke was right. We had supporters coming up to us who hadn’t saw an Ulster title and have never saw it since.

“They wanted to talk to you about the game and if you had a feed of drink taken, you’d have been talking complete drivel.”

What was it like to be an Ulster champion? Martin doesn’t use the word disbelief.

“It was pure elation,” he replies, settling on the words to sum up coming home with Ulster club football’s biggest prize.

“We had never been there before, there were good GAA people around Loup and it brought everybody together with the buzz of it all. It was probably a shock for the whole of Ulster, but not for us.”

***

“There’s no doubt about it,” Martin answered when asked if missing out on an All-Ireland still eats at him.

He uses the age old “have no regrets” cliché to put their All-Ireland semi-final defeat to Caltra in context. The Galway champions walked a similar path. Winning a provincial title at their first visit.

“That is definitely, definitely, definitely…from playing Gaelic football, that is my biggest regret. No doubt about it, that hurt more than getting beat by Ballinderry in ’02.

“It’s the regret that we were a couple of kicks of a ball away from bringing the wee parish into Croke Park.”

Martin laments the loss of John O’Kane in a challenge game, forcing a selection reshuffle.

“Unfortunately, it wasn’t meant to be,” he said of their defeat, with goals from brothers Noel and Michael Meehan being the difference.

“Big John got injured and was a huge loss to us. You always talk about the Brian McGilligan and Anthony Tohill partnership…we had the same. John was a workhorse and he let McBride play the football.

“We had to chop and change our team and it didn’t work for us. We couldn’t replace him and he was a huge, huge miss against Caltra.”

Outside of the major superpowers, club GAA comes in cycles. The current Loup team face into games with Ballinderry and Kilrea over the next two weekends.

They can’t make the quarter-finals, but still gave Sleacht Néill plenty to think about for 40 minutes of their previous outing. There are enough shoots to suggest they’ll get the two wins that give them a chance of climbing away from a relegation play-off.

Fionntan Devlin is the manager and Dara Joe Martin is now a player. Welcome to planet GAA and its generation game.

There will always be football in Loup. Colum Rocks carried a baton that continues to be passed on.

And the gold star on the back of their jerseys will be a constant reminder, to generations who follow, of the men on 2003 and a year they were Kings of Ulster.

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere