Dominic McKinley has played and coached at the highest level. Hurling and camogie remain very much in his blood. He sat down with Michael McMullan to chat about his career.

DOMINIC McKinley, one of seven sons, came in the middle of John and Jane’s family of 13. Across from their home in Ballyknock, the McFaddens had 13 children. The Lavertys had a dozen.

There were hurlers aplenty in their corner of Loughgiel and rarely an idle moment. Growing up, the field at the back of their housing development resembled a cross between a battleground and their version of Casement or Croke Park.

Every evening without fail, there’d be close to 40 boys and girls hurling on a slightly inclined some 70-metre long arena. There were thrills and spills, arguments and scelps. It was learning in its rawest form in the school of hard knocks.

The years may have passed, but McKinley remembers it all. Sitting over a cuppa, his dancing eyes and facial expressions say more than words ever can. His career unfolds with pride and precision.

Everyone had a nickname and if you didn’t, it wouldn’t take long for one to be conjured. McKinley has no idea why he became known as ‘Woody’. It wasn’t a family line. It just arrived and stuck.

“The only person who ever checked it was, God rest her, my mother,” McKinley laughs.

The door would knock. “Is Woody in,” came the question. “Naw, but Dominic is in,” she’d quickly reply.

“We lived in a three bedroom house at the start,” McKinley said. “Mammy and daddy were in one room, the girls had a room and the boys were in another.”

Jane was the typical GAA mother, a nervous but equally proud spectator. When she sadly passed away, her wishes were to have all Dominic’s photos left aside for him. They were proudly gathered over the years and now join the framed trio of Loughgiel, Antrim and Sleacht Néill All-Ireland final jerseys.

The McKinleys lost their father John, suddenly, on the day of Loughgiel’s 1990 All-Ireland quarter-final. Dominic was captain and recalls getting a phonecall before leaving for the game. With British champions Desmonds having crossed the pond, the game went ahead in the Loughgiel skipper’s absence.

“Daddy cared about it,” Dominic said of his father’s interest in his sons’ hurling careers. If they’d struggled to make any of the teams, John would insist their name didn’t fit.

“You had to go and build a reputation for yourself and it’s tough at times trying to get your name established as a hurling person,” McKinley said. “You’d be in and out, in and out. There are ups and downs in it for everybody.”

His brother Gerard was on the 1983 All-Ireland winning team, but Dominic took it on to county level and would later have three different stints as Antrim’s senior manager.

Their sister Bernie has lived in Canada for the last 50 years. She comes home regularly and the rest of the clan are close to home.

“Travelling was never for me,” Dominic insists. “I could never stay away. With the hurling and the Gaelic and staying around the house, I could never see myself going away.”

Hurling ruled the roost, but McKinley’s fleeting interest in soccer took him from Corkey FC to Ballycastle United and an attacking partnership with Paul McKillen.

McKinley got the call for a trial with Ballymena United, with the chance to pursue the big ball game further. But it just didn’t feel right.

It was then that Neilly Patterson, father of Loughgiel and Antrim ‘keeper Niall, steered McKinley towards a hurling path.

“He was an important man in my life,” he pointed out. “Neilly asked me if I’d not rather play in Croke Park in front of 60,000 instead of standing up Clough Rangers with 10 or 15 people around the field shouting at you.”

In an era when Loughgiel were jostling for supremacy in Antrim, there was always talk about club coming before county. Neilly and Gilly McIlhatton would constantly sell the county, always making a solid case.

“To me, my county and club were equal,” McKinley still insists. “In the early parts of it, you never thought you’d get there with the county.

“Then came ’85 when we started to get close. There was Offaly that year and we were very close, then in ’86 there was a great game with Cork in Croke Park.

“After that we were thinking if we pulled ourselves together for the next five or six years, there is an opportunity for us.”

***

McKinley’s Loughgiel underage team tasted success as they headed up towards senior level.

A North Antrim u-14 Féile success was followed by a county final defeat to a city select team. It’s something that still doesn’t sit well, but he files it away under the learning to grow up category.

Once in the minor grade, the next stop was the fringes of the senior team. Show enough in the junior game and you’d get the call to stay stripped out for the senior game that followed.

More than half of that underage group made the cut at senior at a time when hurling and mass was all Loughgiel had to offer.

“You’d hear that a lot, but there was practically nothing else to do. Chapel was very much the way you were brought up,” McKinley said.

Neilly Patterson would always be on Holy Communion watch and failure to show constituted a black mark.

It was Patterson who handed a 19 year-old McKinley his championship debut against Sarsfields in the same year he got the first call to join the county squad.

Patterson had to read the riot act four three years later as Loughgiel’s All-Ireland winning campaign looked highly unlikely when Glenariffe beat them in the Feis Cup.

“You couldn’t imagine us ever winning it (the All-Ireland),” McKinley said, recalling the afternoon Patterson almost tore the paint off the Glenravel dressing room walls.

“Neilly, God rest him, he told nobody to get changed. We just sat there in our gear until the car park outside was empty.”

It was time for the hairdryer. Patterson’s language was unforgiving and nobody was spared. It was total honesty, a clear the air meeting in every sense of the word. The Loughgiel players’ bravery and pride in the jersey were called into question in the strongest sense.

“He emptied everything,” McKinley recalls of a group with some of the club’s greatest stalwarts being placed at a fork in the road. Either represent Loughgiel Shamrocks properly or stay at home.

“We took it on the chin, went away and came back on Tuesday night,” McKinley said of their first step on the ladder of redemption

“Gradually, we got going and played Sarsfields in the championship. We weren’t that good. It was the same against St John’s but we were gradually getting better.”

It was an era when Ballycastle had been in the previous five finals, winning three in succession and were a puck of a ball from toppling Castlegar in the 1980 All-Ireland final.

“The (Antrim) championship was very competitive and if you were off a wee bit on the day, you’d be knocked out,” McKinley said.

A one-point win over a first time champions and a fancied Cushendall in the semi-final was another step. McKinley slotted a vital point late on, but the Shamrocks’ defence needed to close down Dominic McKeegan as the ‘Dall came in search of a game-saving goal. Alastair McGuile was unmarked. One hand-pass and he’d only Niall Patterson to beat, but Loughgiel closed the door and it was another fine margin in the All-Ireland story.

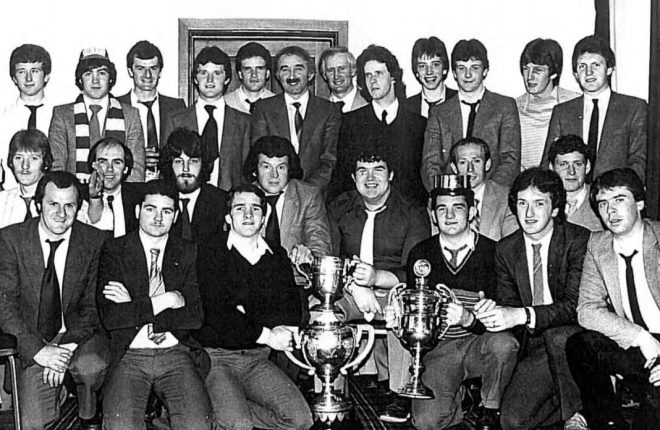

KING OF CLUBS…Dominic McKinley (front,second from right) was part of Loughgiel’s first All-Ireland winning team in 1983

It set up a final with Ballycastle. On a day their minors hit eight goals in a final win over Dunloy, Loughgiel were 5-9 to 3-7 winners over Ballycastle and the Volunteer Cup was decked in red and white ribbons for the first time in 11 years.

Aidan McGarry’s early goal was the key score in a 1-9 to 0-9 Ulster final victory over Ballygalget before it was time to up the ante once again with a training regime that could only be described as gruesome. Any other word wouldn’t do it justice.

“We were on the field on a Tuesday and Thursday night, running a minimum of 25 laps…all with just one floodlight,” McKinley recalls of the torture trainer Danny McMullan put them through.

“You can imagine how boring that was, but everyone was at it. At one point, there was snow on the ground, but you just kept running.”

It was followed up by a series of press ups and sit-ups. There was the solace of being indoors, but the bare concrete floor was tearing off the skin.

“We weren’t even wise enough to put something on our back,” McKinley adds. “That was our conditioning work and our fitness. You did that and came back the next night and did it again.

“Danny was into building up the mentality. He’d be telling us it was about putting fuel in the tank for another day.”

That day was a win over Tipperary side Moycarkey-Borris in the All-Ireland semi-final, thanks to goals from Paddy Carey and junior Aidan McCarry.

St Rynagh’s of Offaly now stood between Loughgiel and hurling dreamland. With the sides level in Croke Park, their endeavour was almost undone when Gerard McKinley ran across county star Padraig Horan. The tangle of legs resulted in a free and a chance to win the title for the Offaly men.

“Mammy had to leave before the end of the game. She prayed all the time and couldn’t watch matches,” Dominic said.

“She left Croke Park when the free was given. With Gerard being her son, she was thinking if it went over everybody would be blaming him.

“Fr McBrearty said if it went over he was leaving the priesthood,” Dominic jokes about the decisive miss, the moment Loughgiel were granted a second bite at the cherry with a replay back at Casement Park.

The team was managed by an astute collection of men – Neilly Patterson, Dominic Casey, Liam McGarry, Dan Carey and Danny McMullan, but a priest in the camp was always important.

“With our run with Antrim, we had Fr PJ McCamphill,” McKinley added. “It helps people. Everybody has different circumstances at different times.”

Nowadays, management teams employ performance coaches for a similar effect. McKinley agrees.

“You could have a chat with him about things going on in your life. We had Fr PJ and Fr McBrearty, they had an important part to play in helping people,” he pointed out.

It was the same for the replay, with Bishop Daly dropping into the dressing room to wish the Loughgiel players well before their final step of a magical journey.

Brendan Laverty’s 22nd minute goal was the difference as the Shamrocks led 1-7 to 0-7 at the break with all still to play for.

Aidan McCarry added a second goal with 10 minutes to go and a late consolation goal from Padraig Horan wasn’t enough to stop Loughgiel on their way to a first All-Ireland title.

“Even yet, you get a shiver when you talk about it,” McKinley said, remembering the unbelievable feeling of being ferried into Loughgiel on the back of a lorry as All-Ireland champions.

***

At county level, Antrim’s stock was rising, but the arrival of Jim Nelson as manager was the “icing on the cake” for a group aiming to make their mark on the All-Ireland stage,

Nelson’s fingerprints were all over Loughgiel’s 2012 All-Ireland title, but McKinley hails his “placid” nature at the helm with Antrim. The new manager wiped clean any excuses a player could offer for not committing to Antrim’s desire to reach the top.

“What’s an excuse?” was Nelson’s first question to the squad.

Babysitters would be made available at training if players were struggling with childcare arrangements. Anyone needing shift work covered on a Saturday to free up time for hurling was accommodated. Money was available and it would be sorted.

“I don’t think anyone needed the babysitters in the end, but Jim left nobody with any excuses,” McKinley said.

“All we had to do was worry about playing hurling. Then, there was his training expertise and the skillsets he brought.

“People are now doing three-ball routines and high intensity and pressure, Jim was doing that then. He was tactically very astute and he was preparing you, with the psychology of it all.”

Nelson was a religious man and it was like the Loughgiel scenario where Neilly Patterson insisted on mass, something McKinley brought into his management tenure.

The Antrim minor teams he oversaw and toured the country with were kitted out and seated at mass. It was the same with Sleacht Néill camogs.

“I knew (some) people didn’t go to chapel, but we were a group and everybody was going to be there, dressed the same,” McKinley said. “It’s another night we’ll be together to chat and that’s very important.”

McKinley made his debut at the age of 19 in an All-Ireland B game against London in Loughgiel, with Neilly Patterson and Gilly McIlhatton giving him the call. Kevin Donnelly’s broken finger forced him to answer the emergency call at full-back.

“I was serious nervous about it. I had been used to playing centre back, so it was very different going from (number) six to three,” McKinley said of his debut. There were mistakes, but was steady enough to launch a career.

Antrim had two chances to land a first All-Ireland senior title. The first came in 1989 when Olcan McFetridge lit up Croke Park in their semi-final win over Offaly, but the final was a step too far against a rampant Tipperary team hungry for silverware.

BEFORE HIS TIME…Jim Nelson was a huge influence on any team he was involved with

It’s something he always thinks about. Two years later, they had Kilkenny almost beaten before being pipped at the post. But 1989 was different. Antrim didn’t keep a lid on the media circus that hangs on a first ever final appearance.

“It wasn’t right,” McKinley said with a regretful tone. “Looking back, it shouldn’t have happened and we should’ve said ‘naw’.

“When you came home at night, even before you got your dinner, there were cameras at your house. It was a bolt out of the blue and we should’ve parked it. It is something I have learned from, in dealing with the (Sleacht Néill) camogie team.

“With the Gaelic Life (awards night), I knew they were cross, but I just didn’t want the girls at them,” McKinley admits.

“If it was the right time, yes. Ten days prior to a match? Naw, this is so, so important. It’s a 10-day period when nothing else matters and nothing else gets in the way.

“Everything is shoved to the side…everything. You focus on the small things like your skills, the shooting and the tackling, getting ready for this day and you are going to get everything. You can’t have distractions.”

McKinley insists 1991 was Antrim’s best chance of the biggest prize. Two years wiser, they “threw it away” in an All-Ireland semi-final they bossed Kilkenny

“We probably were in a position to win it and we should’ve,” he said of their 2-18 to 1-19 defeat.

Antrim were in the driving seat until Eamonn Morrissey pounced on a rebound to score a second Kilkenny goal after Pat Gallagher had saved from Christy Heffernan. Morrissey and DJ Carey added points to seal victory.

Michael Cleary hit 1-6 as Tipperary won the final, but it was Antrim’s best chance at getting their hands on the Liam McCarthy Cup.

“I played number six for about nine or 10 years and then (number) three for four or five. There were a lot of ups and downs, but I was proud of the position and to hold it,” McKinley said of a career that lasted 17 years in total.

“When I reflect on it, every day you go out, you are on one of the best players, an 11 who is very good.

“I had my bad days, but I always say the target for any individual was to have more good days than bad days and deal with your bad days.”

McKinley praises the input of Michael O’Grady for prolonging his career after being brought in by Jim Nelson.

MAKING THE STEP…Dominic McKinley in action during Antrim 1989 All-Ireland semi-final win over Offaly

“Different people teach you different things,” he recalls, looking back on the paranoia of others thinking his best days were behind him.

Ahead of the 1993 All-Ireland semi-final, the gremlins in McKinley’s head told him John Power’s running ability was going to be too much for him.

Sensing the unease, O’Grady questioned McKinley’s concern before handing him a video of Power in action. The homework lesson was about a focus on positioning and reading of the game.

Top players will always make telling runs and McKinley’s passport to success would now come from out-thinking his opponents.

“Better players than me would not be able to do anything, I had to accept it and get to more breaks than him,” McKinley said of his plan for Power.

“It was the best piece of advice I got through my whole career. It was simple, but I wasn’t thinking of that, I was just thinking of him running and me not getting near him.

“He (O’Grady) was giving me the skillset to challenge for the breaks, advice for the rest of my days and to pass on. People may say it’s not a big point, but it is a big point if you are struggling in your head.”

The new advice helped him for the “four or five” times he’d be matched up with Power, including a Railway Cup game at Casement Park.

“I remember going across to the sideline and a man in the crowd shouting “that’s the hurling Woody” when I made a block,” McKinley said.

“Power would be delivering low ball and Michael (O’Grady) was telling me to always keep my hurl low if he was ever to get away from me.”

Another important element of learning for Dominic McKinley is how valuable enjoyment is within the inner sanctum of a team.

There is the love of Croke Park. Winning an All-Ireland Club brings a connection with finals’ day even though moving away from St Patrick’s Day takes away some of the attraction.

Headquarters is a venue to be embraced and not feared. Jim Nelson brought in Craig Mahoney, a psychologist who was involved with Derry footballers’ All-Ireland win.

“He gave us this belief to enjoy things form the minute you get on the bus, until you get there, going to the hotel in Malahide and the prep for the game,” McKinley recalls, something he passed on when he became involved in coaching.

Mahoney’s methods were about giving players energy and McKinley feels it was a factor in him always doing “quite well” at Croke Park. It was about more than the skills, rather immersion in the game and the entire situation.

***

When McKinley’s playing days came to an end, coaching was always going to be the next avenue. The first of his spells as Antrim senior manager came immediately, before moving across the Bann for the first of two terms with Derry seniors.

“Standing on the sideline…that buzz, you’ll not get it in a bar,” McKinley said of the attraction of remaining in the game.

His work with Ulster GAA gave him the opportunity and a grant to delve into his coach education with a week at Scottish soccer giants Celtic.

He remembers former Hoops’ legend Danny McGrain comparing coaching to chasing paper in the wind. Only so many are caught and how young players are the same. It’s about concentrating on those who buy into development. McKinley’s mind was like a sponge, looking for any detail.

“Antrim was a bit like Celtic under Martin O’Neill,” McKinley said, remembering his comparison at the time.

“He worked with very little resources and got a great deal out of them and I wanted to get an insight to that.”

The visit was about picking the brains of the coaching staff and taking away as many nuggets as could be relevant to coaching hurling back in Ireland.

It was a “wonderful” experience looking on at the habits of players such as Bobo Baldé, Neil Lennon and Henrik Larsson. McKinley scoured the extra work they put in away from training to get an edge.

With the hurling fraternity in Ulster cut away from the heartlands of the game, distance for challenge games has always been a problem. For McKinley, it was about looking at Celtic and seeing how they maximised everything. Just like O’Neill had done at less fashionable clubs, it was about squeezing every drop from a squad.

“Tommy Burns, God rest him, I spent a lot of time with him,” McKinley adds. “The learning I got from him helped me as a person. Individually talking to players and how you communicate with less words and better meanings. Making sure what you say is proper and cutting down what you talk about.”

McKinley and his former teammate, Terence ‘Sambo’ McNaughton made great progress in their two seasons with Antrim minor hurlers.

They left no stone unturned in their preparation, dragging them into the All-Ireland conversation. In 2005, beaten finalists Limerick pipped them in the All-Ireland quarter-final with Joe Canning’s Galway doing likewise 12 months later.

“They were special Antrim teams,” McKinley said. “We had them to the pin of their collar and should’ve won both matches.”

Before that, Antrim minor teams didn’t have the preparation done. It was more of a box ticking exercise, doing enough to win Ulster, but lacking the ambition to search for the bigger prize.

Paul Shiels, Neil McGarry, Eddie McCloskey, Cormac Donnelly, Neil McManus and Arron Graffin were some of the names to graduate from a “serious” group.

SAFFRON DAYS…Dominic McKinley and Terence ‘Sambo’ McNaughton changed the mindset of minor hurling coaching in the county

“We knew their potential,” McKinley pointed out. “We changed the template and trained maybe 70 times and had about 15 matches.

The joke at the time was that if you didn’t see the minor bus heading to a challenge game down the country, you’d meet it on the way back up.

Sambo and Woody’s plan was development. It was about having an identity and adding something extra to the excellent work done in their clubs, who were “first and foremost” in the players’ pathway.

At the start, it was hard to get the respect of southern minor managers until they beat Dublin, three times, and mixed it with Wexford and Offaly.

Then, the excuses of club fixture clashes dried up and Antrim minors held enough clout to be sought out for challenge games.

“There was a threat there and we knew we were on the right path,” McKinley said. “It was the same with Sleacht Néill camogs at the start, until teams realised you were a serious threat and wanted to dig deeper.”

Hindsight always offers the easy answer and McKinley regrets not staying with the minor project for longer, to help with the production line.

The two years was about giving an identity to players who walked the extra mile in the Saffron cause and raised the standards.

“We wanted the lads to wear gear that nobody else would be allowed, because they had earned it because they were different,” he explains, with the conversation going deeper.

“Like the All-Blacks, we had them cleaning changing rooms, cleaning our tables when we were finished our dinner in the hotels,” McKinley proudly added.

“We were getting emails back from hotels about their behaviour, the way they brought their plates up and always said thank you.

“People might say it’s not a great deal, but it is important. You create the person and everything comes in in behind. The person is very, very important in life.”

***

McKinley has lived in Dunloy for the last 40 years, longer than he has lived in Loughgiel. With his wife Maureen, they marked their 40th wedding anniversary earlier this month.

Their son Conor is part of Gregory O’Kane’s squad, craving to win the elusive All-Ireland title. One of their daughters, Nicola, didn’t follow the camogie path after underage.

Their other daughter Ciara would win Ulster and All-Ireland medals with Antrim, but her 1-1 for Dunloy u-14 hurlers in a Féile hurling final against a Loughgiel team managed by her father is something he’ll never forget.

“I looked after the u-14s and u-12s in Loughgiel for three years at that time. I said to myself, that day of the final if I ever get out of this I will never be in this situation again.

“That’s probably why I ended up going outside and looking after teams and staying away from the club my children were involved in, because of that final. My children played for Dunloy and I didn’t have a problem with that. I just got on with it…that’s life.”

A call from Thomas Cassidy to get involved in the Sleacht Néill camogie team opened another chapter in McKinley’s coaching career.

His imprint was over their three All-Ireland successes, something he knew wasn’t beyond the realms of possibility almost as soon as he arrived at Emmet Park.

Cork superpower Milford had won three of the previous four titles, but were gone from contention and McKinley began to think ahead.

“There were a few new teams. I told the girls we had as much right as they had and whoever trains hardest would win it.

“Once you make that breakthrough, it will make it so much easier for the rest of your lives and your club as well.”

Like Antrim getting to the 1989 final and Loughgiel winning the 1983 hurling All-Ireland, Sleacht Néill’s breakthrough was special.

“There is no substitute for the first team ever doing it. You break ground for everybody, even in the province,” McKinley said. And it raises the bar for others.

Sadly, Thomas Cassidy wouldn’t be around to see the Sleacht Néill camogie and hurling teams he helped shape climb to the top of the tree in Ulster, passing away after a battle with cancer.

McKinley vividly remembers the night Thomas broke the news of his illness to him as they were locking up the dressing rooms.

“I noticed he was fidgeting,” McKinley recalls, before hearing Thomas uttering the words he’d never forget – I’m finished.

“I told him if he was finished with the girls, then so was I,” McKinley told him, before learning of Cassidy’s diagnosis.

The pair sat down on the step and tears flowed as the realisation began to sink in.

“I’d sometimes call into Mullins in Kilrea for an ice-cream on the way home from Sleacht Néill,” McKinley pointed out. That night, when he pulled the car in, there were more tears and he couldn’t face it before continuing his drive home.

“Even now, talking about it…inside a couple of years, I grew to know this man like my father. He had so much respect for me, and me for him.”

Sleacht Néill regained the Derry title in 2015, but came up short in the final against Loughgiel.

“I knew things were happening that year and Thomas was going downhill,” McKinley said.

“Eilís and Aoife were on their knees beside me standing (after the game). I knew they were thinking he was not going to be here to see this (Ulster title) and he nearly saw it.”

The raw materials were there. The six missed goal chances, including a rasper off the crossbar, could be polished up. Sleacht Néill were going to have their day. It was just a matter of getting the heads down and righting the wrongs.

WE DID IT…Dominic McKinley pictured with the late Thomas Cassidy, his daughters Eilís, Bróna and Aoife after Sleacht Néill’s 2015 Derry final win over Swatragh

Thomas didn’t get to see it, passing away between the 2016 Derry and drawn Ulster finals. On the evening of their father’s funeral, Bróna, Aoife and Eilís were at training ahead of Sunday’s decider.

“I remember chatting to ‘Sambo’ about it and he brought back Jim Nelson’s question about an excuse was…three girls at training the day after burying their father,” McKinley explains, with emotion in his voice.

The final ended in a draw, with the replay set for six days later at Glen in what would be another epic game with Mary Kelly winning the goal with a last-gasp goal.

“That day down there,” McKinley said, gesturing towards Glen pitch from his seat in Maghera’s Walsh’s Hotel.

“The whole thing, the 5,000 people at it and the situation with Thomas…it took so much to get over that line. Sometimes you wonder if there is a God, but there had to be a God that day.”

When they finished the job with a first All-Ireland title in Croke Park, McKinley found himself looking up to the sky. Mary Kelly’s goal again did the trick, with Eilís curling over a wonder point to seal the deal.

“Thomas wanted so badly to win Ulster and get a crack at an All-Ireland…that Ulster final, it was one of the best days of my life,” McKinley admits.

He was exposed to more learning in the Sleacht Néill chapter. After the scar tissue of losing to Eoghan Rua in 2014, Billy Dixon was brought in to help the girls manage their emotions on championship days. There was too much talent for the minds to come up short.

There was to be no shouting and roaring in the dressing rooms, replaced by a calm walk out onto the pitch with each player in touching distance. Handshakes and high fives, it promoted even more togetherness.

McKinley picked up another nugget. Referee decisions, no matter how frustrating, had to be accepted. It was all about energy and example.

“I wanted to learn how to deal with referees,” McKinley admitted. “Their (Sleacht Néill players) behaviour is my behaviour and my behaviour is their behaviour.”

As the conversation ends, McKinley heads off to Emmet Park for another evening of coaching. Looking back on his career, two Antrim, two Ulster and one All-Ireland title “probably” wasn’t enough. There are the regrets of 1989 and 1991 with Antrim, when they could reach out and touch the Liam McCarthy Cup without being able to take it north. But he looks on his career with pride and satisfaction.

He places a great deal of gratitude at his wife Maureen and the children’s door. Nothing would’ve been possible without their support on those evenings of coming in from work before heading to training.

“You can go anywhere and sit down, like now, to talk about Gaelic Games,” he sums up. “It is very important for everyone and the well-being of the young children…I love to see them playing. I love it, I get a buzz and an attachment with people. You have to be able to draw people towards you and get them caught up with you.”

The years have passed. There have been glory days mixed with harsh lessons and loss, but Dominic McKinley’s lifetime of devotion to Gaelic games continues.

Receive quality journalism wherever you are, on any device. Keep up to date from the comfort of your own home with a digital subscription.

Any time | Any place | Anywhere